Do you have a question about history? Send us your question at history@time . com and you might find your answer in a future edition of Now You Know.

Ironically, considering the system is used to describe precise calendar years, it’s impossible to say exactly when the “A.D.” calendar designation first came into being, says Lynn Hunt, author of Measuring Time, Making History and professor of history at UCLA.

Though there are a few frequently cited inflection points in that history—recorded instances of particular books using one system or another—the things that happened in the middle, and how and when new systems of dating were adopted, remain uncertain.

Systems of dating before B.C./A.D. was fully adopted were often based on significant events, political leaders and a well-kept chronology of the order in which they ruled. For example, the Romans generally described years based on who was consul, or by counting from the founding of the city of Rome. Some might also count based on what year of an emperor’s reign it was. Egyptians also used a variation on this system, counting years based on years of a king’s rule (so, an event might be dated to the 5th year of someone’s rule) and then keeping a list of those kings.

But how did we get from that event-based organization to sticking with just one primary moment?

“The history is very vague, because it takes a long time” to adopt this sort of dating, Hunt says. “A.D. is very easy for people to cope with because the life of Jesus is obviously incredibly important in Christian Europe. So Anno Domini, the year of our Lord, is a very easy transition to make, as opposed to dating the year an emperor had reigned in Rome.” Still, even if there’s logic to counting from a single incredibly important event (and dating like this was also the basis for the Islamic calendar), it took hundreds of years to catch on.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

“Christians wanted to get away from the Roman chronology, so they begin to develop a Christian chronology. In Christian Europe Jesus is the obvious point of departure,” explains Hunt. One of the early writers to date this way was Dionysius Exiguus, a monk who, in 525 A.D., was intent on working out when exactly Easter would occur in the coming years. Given the importance of calculating when significant religious occasions should be observed, he formulated a new table of when the holiday would fall, starting from a year he called “532.” He wrote that this method of counting “with years from the incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ” would replace a system based on the Roman Emperor Diocletian’s rule which he termed “the memory of an impious persecutor of Christians.” But just because he used this dating didn’t mean it was popular or caught on immediately, or that he was necessarily the first to or only one to do so.

Practical use of A.D., on papers like charters or church documents, began to catch on in eighth and ninth century England, as Hunt describes in her book, and from there expanded to France and Italy by the late ninth century. But, even as it grew, people continued to use other systems like the Roman calendar.

So what about “B.C’?

Starting with Christ’s birth as a single defining moment—rather than using a succession of rulers one after another, or trying to count from the very beginning of creation—leads inevitably to the fact that lots of stuff happened before. But, Hunt says, B.C. was much harder to implement. Terms referring to this “before” varied all the way through the 18th century.

Some mention Bede, an Anglo-Saxon historian and monk, as an early instance of writing about “before” Christ. He used the same dating system as Exiguus throughout his history of England in 731, which he started with Caesar’s raids (55-54 B.C.) and so mentions years “before the incarnation of our Lord.” Another religious writer, this one a French Jesuit named Dionysius Petavius (a.k.a. Denis Petau), used the idea of ante Christum in his 1627 work De doctrina temporum. New editions continued to be published throughout the rest of the century and it was translated into English, where the abbreviations of A.C. or Ant. Chri. were used. Another option was to use the Julian Period system invented in the 16th century by Joseph Scaliger, who combined several other calendars to come up with a master calendar that stretched nearly 5,000 years back before the year one.

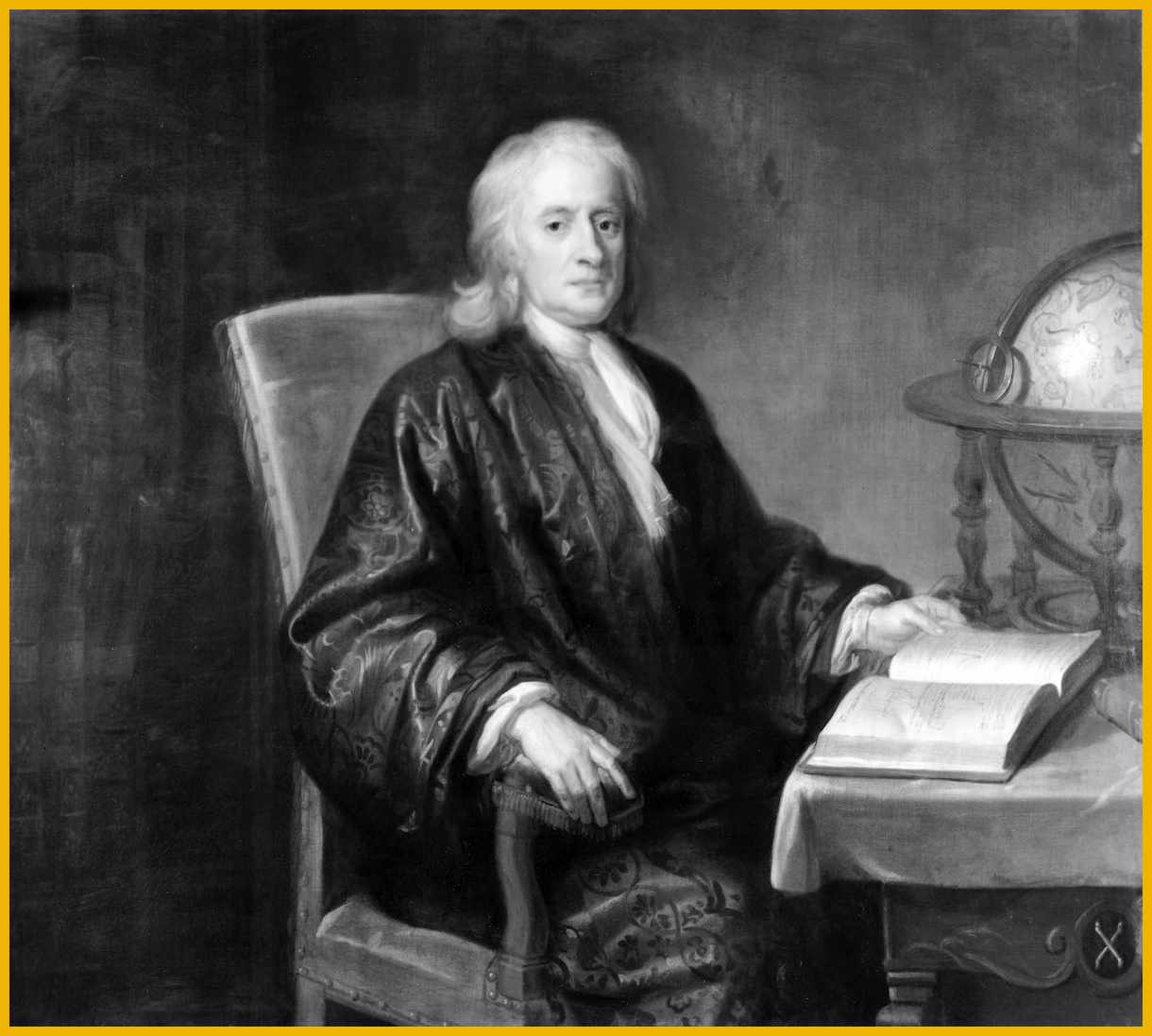

A century or so after Petavius’ work, Isaac Newton wrote a chronology in which he used Petavius’ system—but with a slight change in the wording, using “before” rather than the Latin “ante.” “The times are set down in years before Christ,” Newton wrote, but he didn’t use abbreviations.

“The hinge idea, that there’s before Jesus and after Jesus really only takes root in the 17th and 18th century,” Hunt says.

Newton’s chronology was part of a growing interest in figuring out concordances—links between historical events and biblical events—during the 18th and 19th centuries. Even as some explored these connections, scientists wondered if the geological and fossil evidence they were discovering made sense with the age of the earth supposed by the Bible. Those doubts were possible to explore because the B.C. dating system can reach infinitely far into the past. “It’s becoming increasingly difficult for them to believe that the earth is only 6,000 years old and that gives much more importance to the A.D./B.C. [system],” Hunt says, “Previously it was not that long of a period before Jesus, and now all of a sudden that’s exploding and becoming a potentially huge amount of time.”

And, though it took centuries for A.D. and B.C. to catch on, they stuck. Aas some people stripped the terms of some of their religious connotations by using BCE (“before the common era”) and C.E. (“common era”) instead of B.C. and A.D.—especially in the past 30 years—counting from the birth of Christ endures. But even these newly popular terms have a history. When the language of how to refer to the system hadn’t yet crystallized, people used a variety of terms including “common era”as early as 1708, and the Encyclopedia Britannica used common era to refer to dates, alongside “Christian era,” in its 1797 edition.

A significant portion of this system’s staying power is due to Western colonial expansion and dominance, Hunt says, adding that part of the reason we still use this system is because it’s so hard to change.

“You get used to a certain way of doing things,” she says. “It’s quite similar to the problem of the metric system, which is invented in the 18th century and took a very long time before it could be taken up even in France. Now almost everybody in the world uses it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com