The second National Drone Racing Championship was contested on August 7 on Governors Island in New York City. The winner was one Zachry Thayer, who races under the name “A_Nub.” But the biggest news wasn’t who won. It was that the whole event was streamed live on ESPN3.

You may not have realized there was a first National Drone Racing Championship—that happened last summer in Sacramento, and while around 120 people competed then, almost nobody saw it. Almost nobody saw the World Drone Prix in Dubai this past March either, although 250 teams entered and the winner, a 15-year-old boy from Somerset, England, took home $250,000.

But drone racing already has deep grass roots—there are dozens of local and regional drone races every month. The Drone Nationals which are run by an outfit called the Drone Sports Association, or DSA, are the biggest swing anybody has taken yet to bring the sport to the mainstream.

As young as it is, the origins of drone racing are still shrouded in mystery. “About four years ago you started to see stuff out of Australia about it,” says Nick Horbaczewski, CEO of the Drone Racing League, which notably did not run the Drone Nationals this weekend—not only is drone racing now a sport, there are several competing professional circuits. “About two years ago you start to see communities forming online—forum posts, how do I build a drone, where can I race it,” Horbaczewski adds. The basic idea is, you get a bunch of drone flyers together. You lay out a course. You route the video feed from your drone’s forward-facing camera through a pair of VR goggles, which gives you a drone’s-eye-view of the action. This is called first-person view, or FPV, and it makes you feel like you’re inside the drone, or possibly like you are the drone.

Then you fly the drones around the course at around 80 miles per hour. They make a noise like angry robot bees, especially on tight corners, and there’s a lot of crashing, but it’s hugely fun—people describe it as like being in a video game.

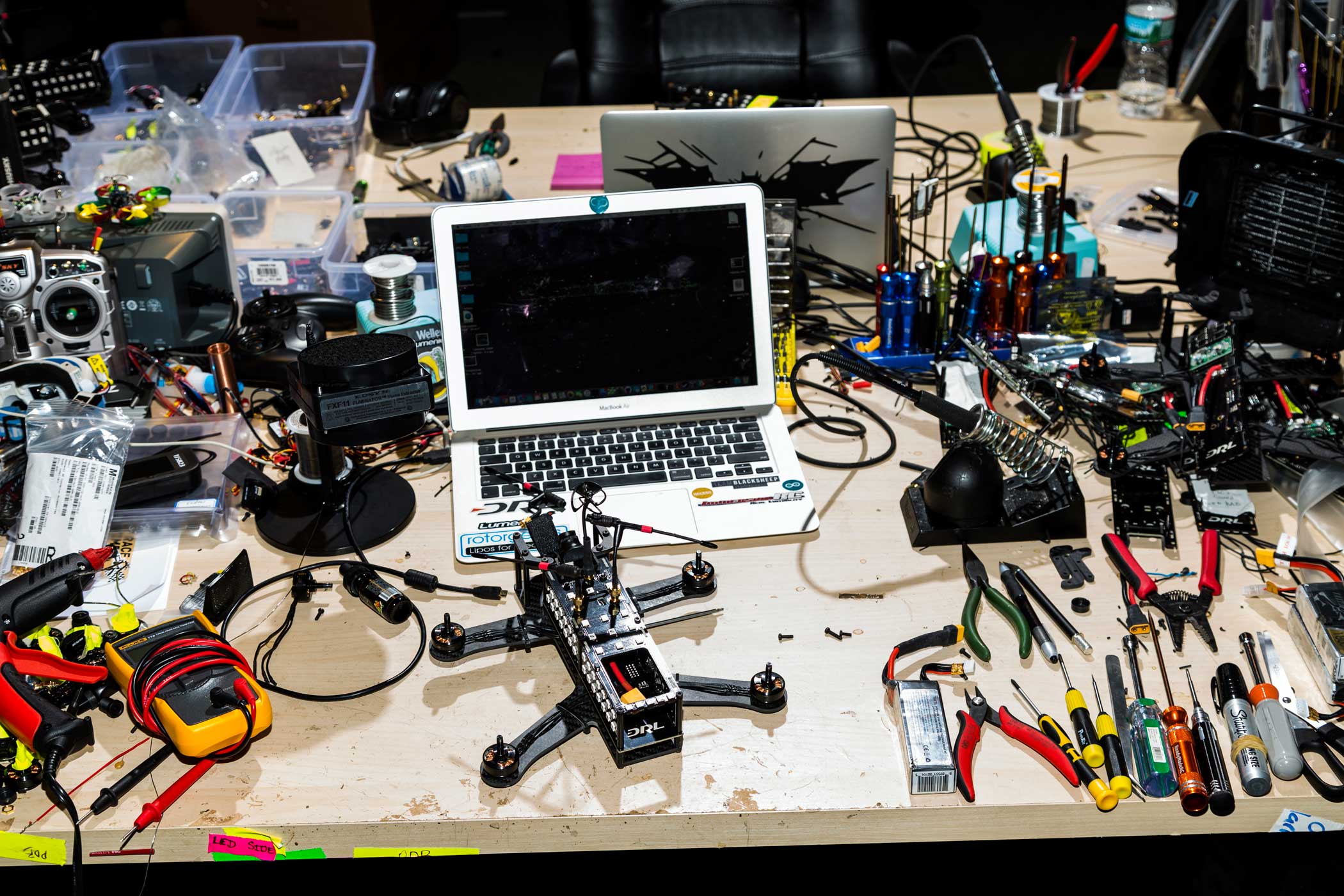

It’s also harder than it looks—racing drones don’t work like those easy off-the-shelf ones. The control schemes are much more complex and hands-on. Instead of an app on your phone you use a fat remote control with two joysticks which you manipulate simultaneously: the left stick controls throttle and yaw, the right stick handles pitch and roll. The first time you fly a racing drone you’ve got about as much chance of keeping it in the air as you do of driving a Formula 1 car out of the pits without stalling. “There’s a lot of calculations, and you’re doing it in three dimensions at very high speed,” Horbaczewski says. “When you watch the really good pilots, it’s like they’re using the Force.”

For the racers it is, by all accounts, as much a mind game as anything else: Uou have to have nerves of carbon fiber to keep your fingers steady under racing conditions. “In other things where there’s competition involved it’s usually gross motor functions,” says Conrad Miller, a father of four from Boise, Idaho, who flies under the name Furadi. “If I’m racing a motorcycle, I’m nervous, but I’ve got my whole body to control this thing. When I’m flying a drone I’ve only got my thumbs. When you have all that adrenaline coursing through you, it’s hard to control your fingers.” Furadi made the finals this weekend and finished fourth overall.

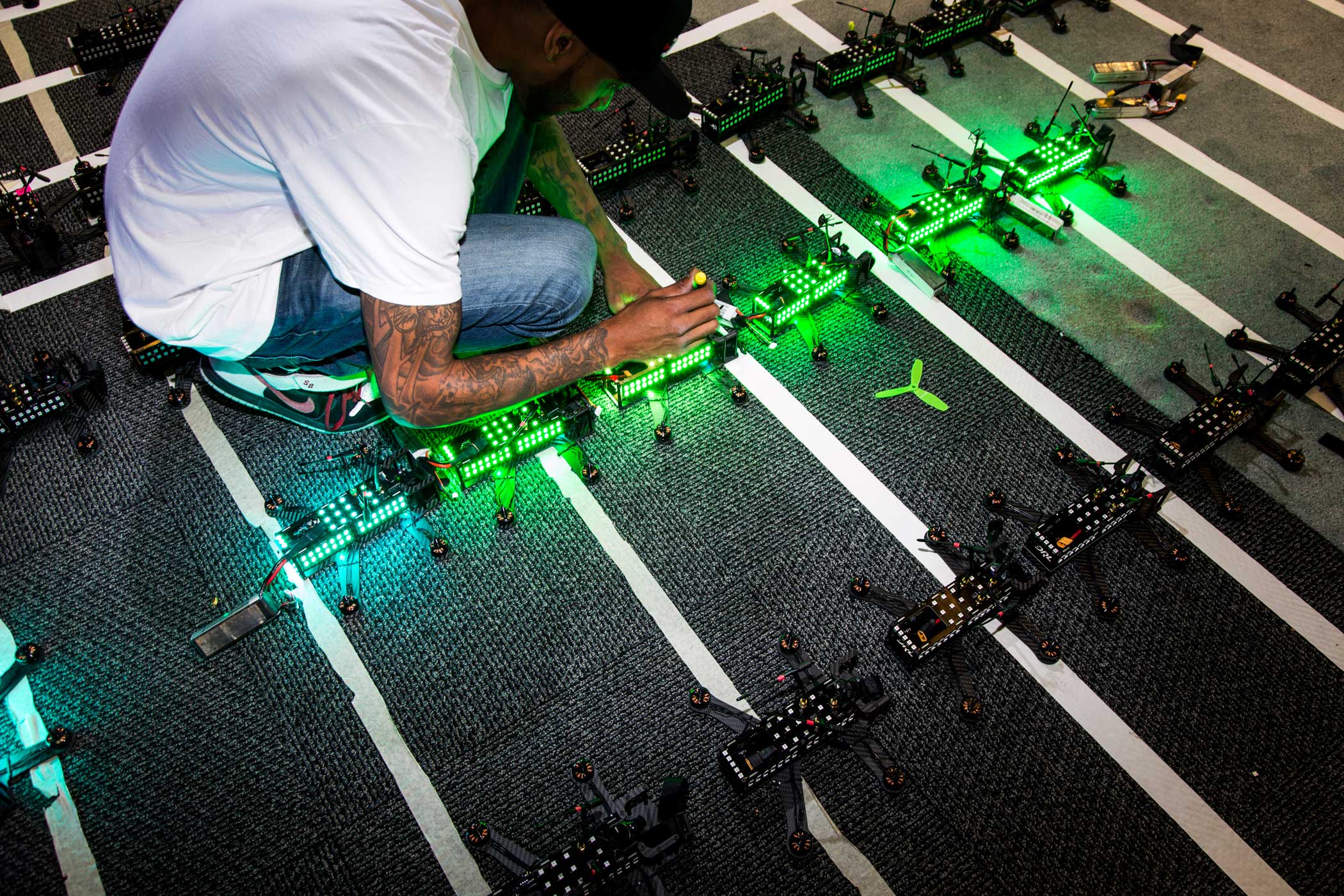

If drone racing is hard to do, it can also be hard to watch: the drones are small, and they tend to look a lot alike, so it’s not easy follow the action or even tell who’s winning. In a professional race the drones are usually equipped with bright colored LEDs so you can tell them apart, but it’s a major challenge for promoters and broadcasters and everybody else who’s trying to turn drone racing into a major-league business. The bar is high: there’s a high rate of infant mortality among newfangled sports leagues—for every Electronic Sports League (booming) and World Surf League (thriving) there’s a National Xball League (paintball).

So far drone racing may be running a year or two ahead of the broadcast and display technology, like VR and augmented reality, it will need to make it must-see entertainment. “We’re going to be entering into the world of multi-stream, multi-screen, multi-broadcast,” says Scott Refsland, the DSA’s chairman and chief evangelist. He imagines a future scenario of blended-reality events where audience members can race along with the pros virtually and remotely. “If you looked at a field with the naked eye, you would just basically see four drones. Whereas if you put on something like Hololens, now there’s 12 drones racing, and you get all the markers, all the various leaderboards, who’s what, who’s where, who’s in first.” Given that the racers are already essentially flying computers, it should lend itself well to high-tech innovation. “It’s a 21st century sport,” Refsland says. “It’s made for that. It’s Running Man–it’s like Arnold Schwarzenegger come to life! It’s The Hunger Games!” (It could be argued that Arnold Schwarzenegger is in fact already alive, and the Hunger Games were actually a dystopian atrocity, but you see what he means.)

The business trends are in their favor, anyway. This year the Drone Nationals attracted some blue-chip sponsors, including AIG and GoPro. According to the NPD Group, drone sales over the six months ending in April of this year were four times what they were in the same period a year ago. The FAA estimates that Americans bought a million drones in the 2015 holiday season alone, with 2016 sales projected at 1.9 million. The DSA is setting up a World Drone Racing Championship in October, to be held at Kualoa Ranch in Hawaii, where Jurassic Park was filmed. We can assume that no expense will be spared.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com