In one of those ironies that border simultaneously on absurdity and tragedy, men have long dominated the trades that make and sell women’s clothing. From Baron Adolph de Meyer to Bill Cunningham, men have also dominated fashion photography as surely as they have fashion design. While a Tuscan noblewoman, the Countess of Castiglione, commissioned the first fashion photographs in 1856, it was a man who took them. And so it’s mostly remained. Designers Coco Chanel, Elsa Schiaparelli Donna Karan and Donatella Versace and photographers Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Lee Miller, Pamela Hanson, and Corinne Day are but exceptions proving the rule.

But I am a graduate of Vassar, what had long been a women’s college. And I have always lived with and loved strong women. So, while researching a book on fashion photographers, I was thrilled to discover that a woman had taken what can only be called the first modern fashion photograph. I wasn’t, however, surprised to learn that a man has usually been given credit for that feat. I’d made a similar, mistaken claim in one of my very first articles on fashion photography.

Even though we all know it’s not really a man’s world, it can certainly seem that way. Men dominate many, if not most, professions. Sociologists and psychologists are better suited to explain why that is than journalists. And this is not a “why” story; it’s a “who” story.

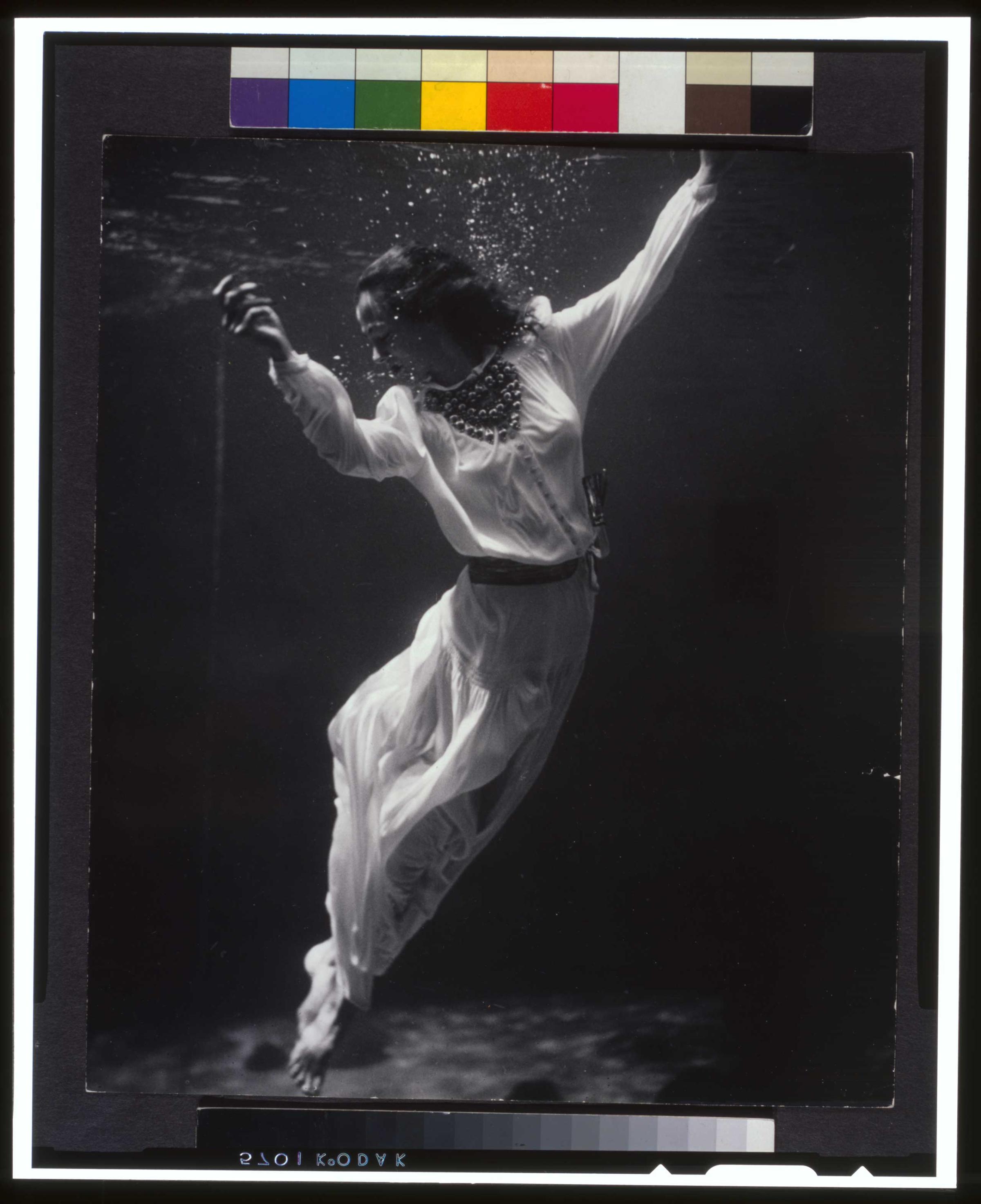

Shortly after Martin Munkacsi, a Hungarian news and sports photographer, was hired in 1933 by Carmel Snow, who was about to become the editor of William Randolph Hearst’s Harper’s Bazaar, she claimed that a photo she commissioned from Munkacsi—of a model in a bathing suit running towards his camera, was “the first action photograph made for fashion.” Snow’s accomplishments were many, but that wasn’t actually one of them. In fact, she’d met the person who did it first in her previous job as fashion editor of the competing Vogue just a few years before.

Antoinette “Toni” Wood Frissell was typical of the women who worked for that society-centric magazine during the Depression. Hired initially as a caption writer, she was a descendent of explorers and gold miners, the granddaughter of a builder of the Northern Pacific Railroad and of a bank president, and the daughter of a doctor who ran a New York hospital. Toni attended the posh Miss Porter’s School in Connecticut before making her debut in society at an Arabian Nights party at her parents’ midtown Manhattan townhouse. The Frissells later moved to an apartment building where Vanity Fair editor Frank Crowninshield and Vogue editor Edna Chase were neighbors. Toni soon married a Harvard-educated stockbroker from another prominent family, the Posts—but, in a sign of her latent feminism, kept her maiden name.

In 1930, Chase brought her to Vogue and in her second week at the magazine, Toni was charged with collecting props for a Cecil Beaton photo shoot of other society women. “Go out and get a crystal chandelier, a lace window curtain, a pair of gold flying cherubs, a baroque mirror, a large glass ball, the kind that fortune tellers use,” the magazine’s society editor told her. “Buy at Bloomingdales a quilted mattress pad and as it is near Christmas, go to a Christmas trimming place and buy some angel’s hair.” She found a flea market where Beaton was known by Elmo, a clerk from New Orleans, “who had a high piping voice and knew all the photographers,” Frissell recalled in an unpublished memoir. “We must be careful not to give him something he has had before,” Elmo warned her of Beaton. “He would n-e-v-e-r forgive me.”

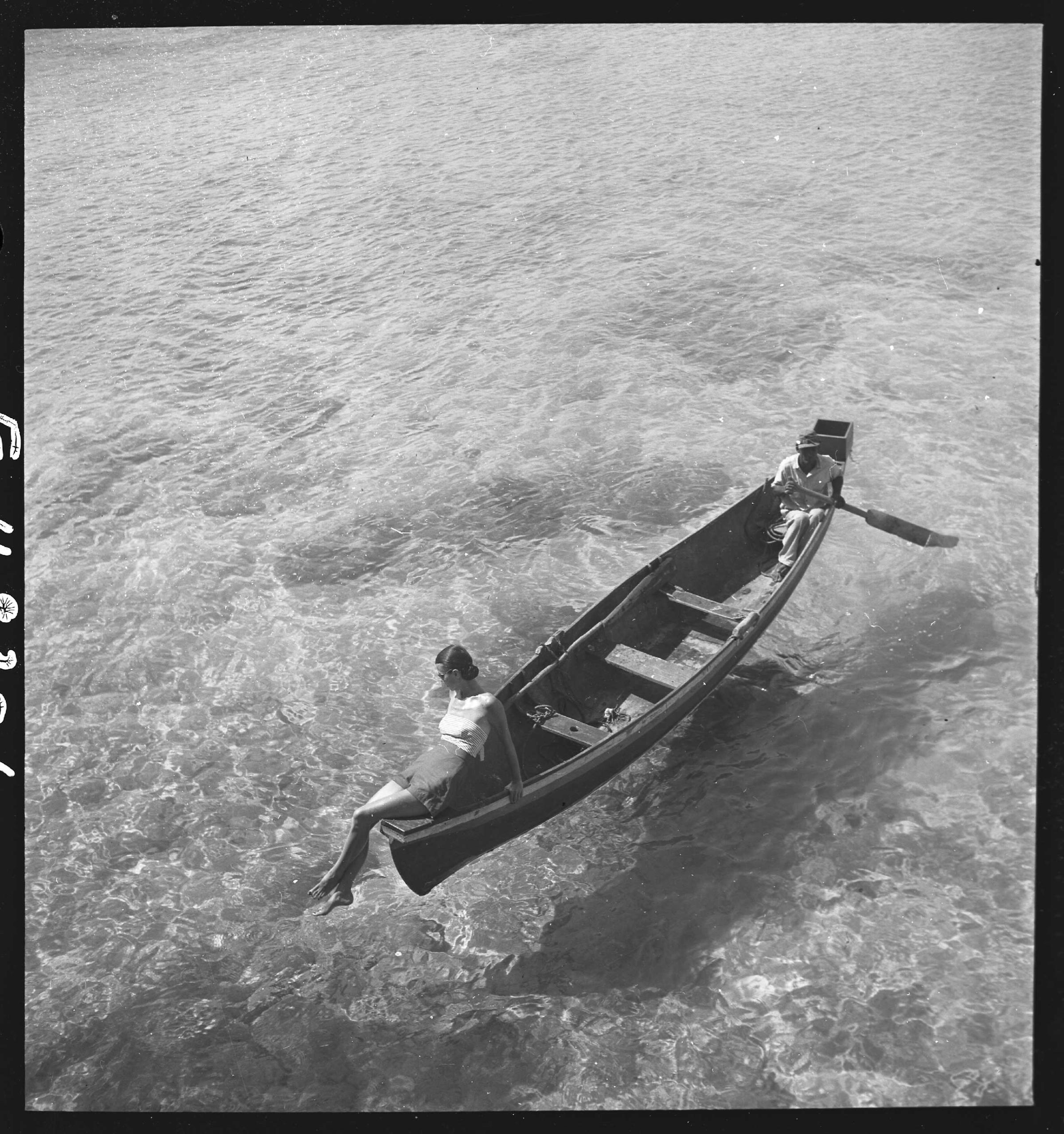

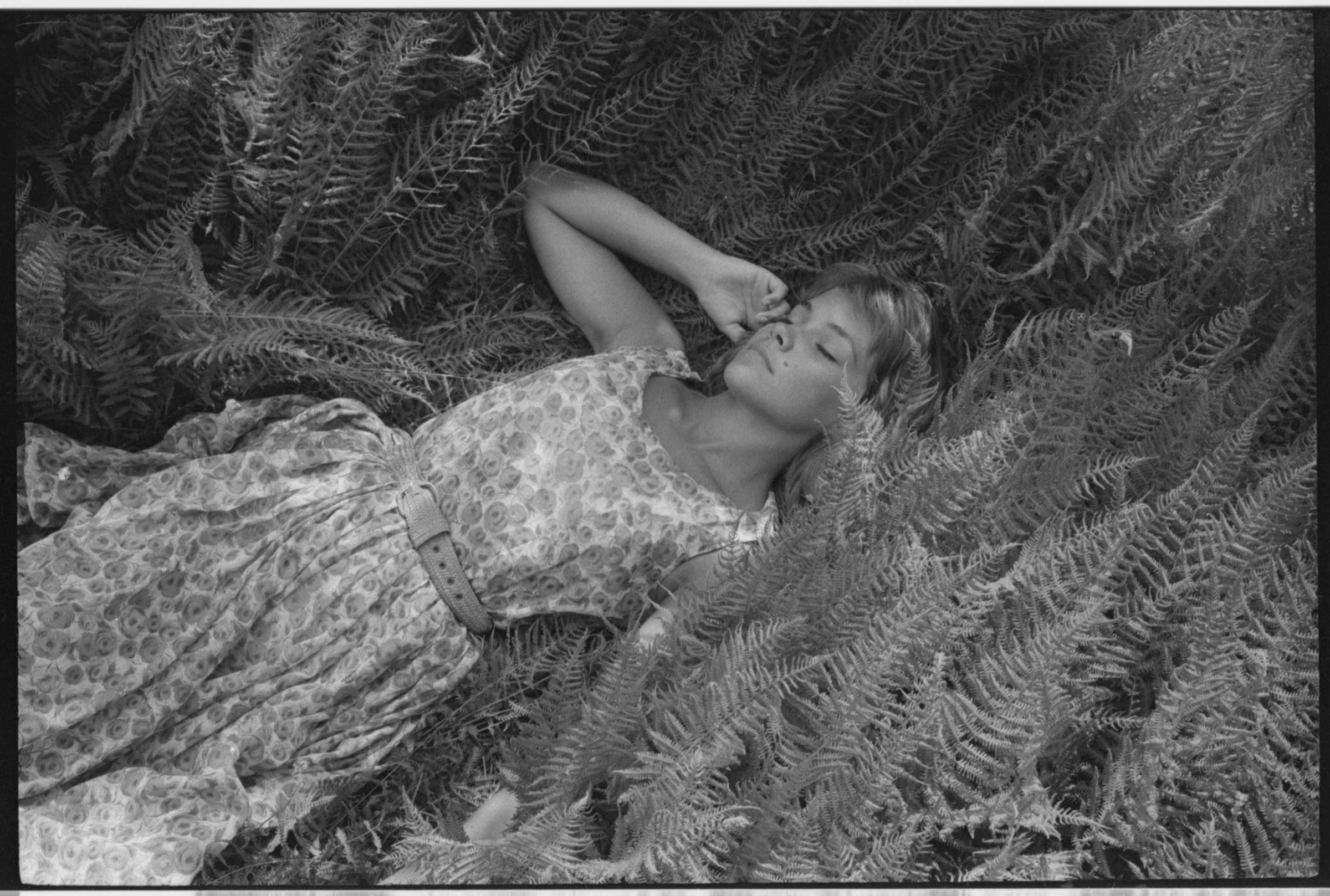

Working for Beaton inspired Toni, and Vogue’s chief photographer Edward Steichen encouraged her, too, so when her brother, an explorer who was handy with a camera, offered to teach her photography, she accepted. Then, early in 1931, Toni’s brother died in a shipwreck, and their mother fell ill. But instead of sinking into despair, Toni pulled out a Rolleiflex camera her brother had given her and decided to distract herself by mastering it. “Why not take pictures out of doors,” she would recall thinking. “How pretty some girl will look running in that field with her hair flying as we did as children. Why not make nature and the world my studio.” She asked society friends with names like Cushing and Brokaw to pose at places like Newport, Rhode Island’s Country Club and Bailey’s Beach, where they all spent summers. She also wrote to photographers and asked for advice and found someone to develop her film and print her pictures.

On her return to Manhattan that September, though, Toni’s employment as a Vogue caption writer ended abruptly. Accounts of how and why that happened vary. In his introduction to a book of her photographs, childhood friend George Plimpton wrote that she was fired over spelling mistakes. Toni, in an unpublished memoir, says the real culprit was the Depression, which had left Vogue’s publisher Condé Nast broke. But as she was leaving, both fashion editor Snow, and Vogue’s art director, Dr. Mehemed Fehmy Agha, a Ukrainian-born Turk, looked at her pictures and encouraged her to pursue photography.

They lacked the courage of their convictions, however, refusing to buy and publish them. Only after she sold a few to Hearst’s society magazine, Town & Country, did Vogue see the light and offer her work. A few were published before Snow left—bitterly, setting off a war between the fashion magazines that would rage for decades. Only after that did Vogue put Frissell under contract. Though she tried working in Vogue’s studio, using an eight by ten box camera, she found she “preferred miniature cameras and all the wonderful things one could photograph quickly out of doors.” More than happy to hitch a ride on her society lifestyle, Vogue was soon buying pictures she took all over the world.

Though he died broke and forgotten, Munkacsi got most of the credit for making the women in fashion photos look like real people. Likely, that’s because the greatest fashion photographer of his era, Richard Avedon, credited the Hungarian as an early inspiration. In his time, the gender-fluid Avedon was the ideal fashion man, obsessed with style, and a master manipulator of images, his own primary among them. In our gender-fluid time, though, when men model as women, women as men, and fashion photography has ceased to be the sole province of men, it’s time Toni Frissell got the credit she deserves, and the posthumous fame that has thusfar eluded her.

Michael Gross is the author of Focus: The Secret, Sexy, Sometimes Sordid World of Fashion Photographers, as well as other books.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com