Speaking at the United Nations in September, President Barack Obama emphasized his commitment to a peace deal to solve the knotty Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Both the Israelis and the Palestinians had taken risks by restarting the process last July, Obama said, adding: “Now the rest of us must also be willing to take risks.”

So far, Obama hasn’t actually assumed much risk. He has mostly hung back while Secretary of State John Kerry conducted months of frenetic diplomacy. But in recent weeks it’s become clear that Kerry’s efforts are approaching a dead end. And it now appears that Obama may be willing to take his first real risk.

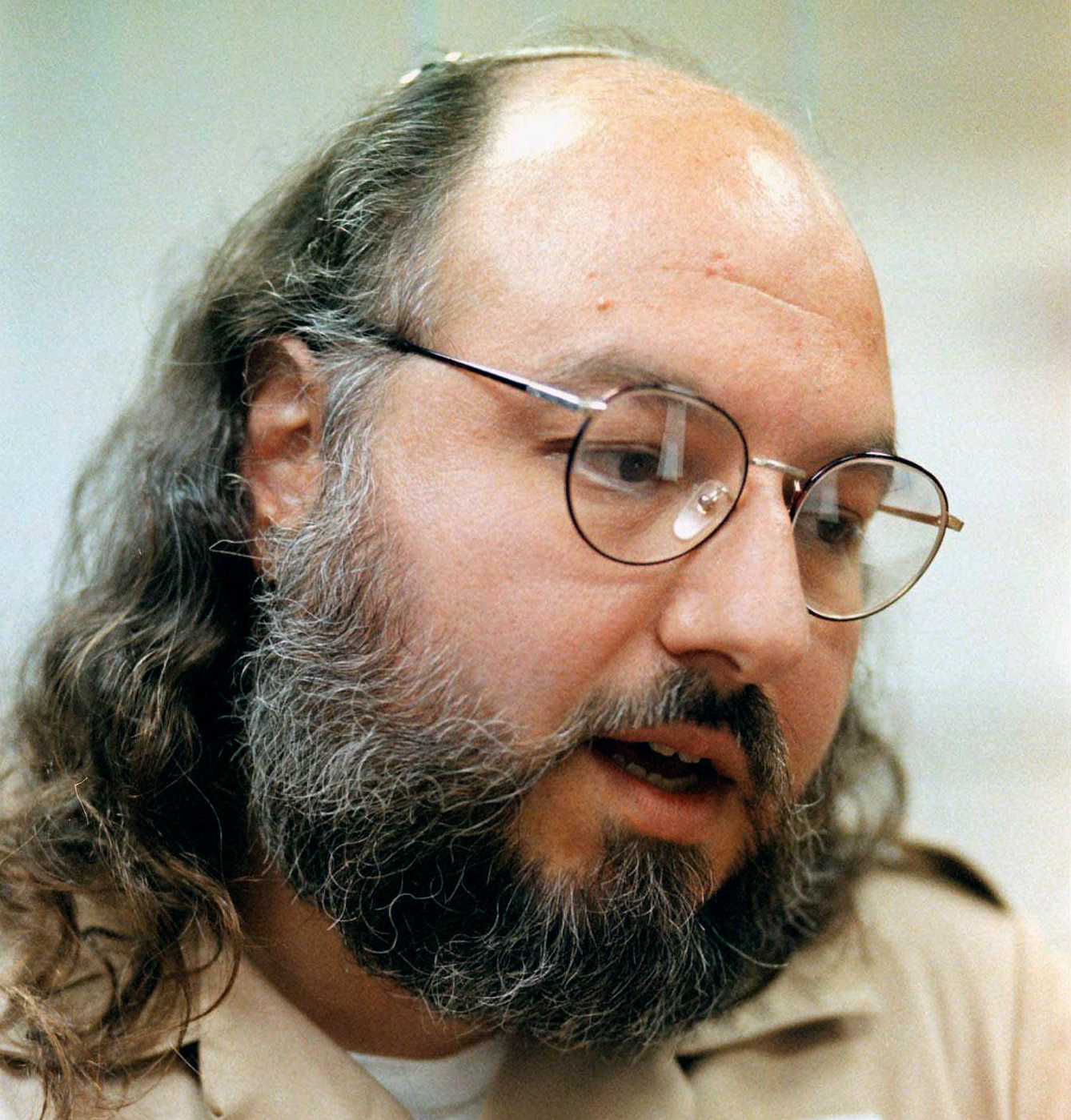

The risk is named Jonathan Pollard. He currently resides in a federal prison in Butner, N.C. Pollard is a Jewish-American who, while serving as a U.S. Navy intelligence analyst, passed American secrets to the Israelis. In 1985, he was sentenced to life in prison—a sentence that many Israelis and some American Jews consider excessive, cruel and potentially tainted by anti-Semitism. Now the Obama administration is considering releasing Pollard from prison as an incentive to keep the Israelis at the peace table, according to reports from multiple U.S. and Israeli news outlets

And so a convicted spy who many Americans have never heard of has entered the picture because the peace process is on the brink of collapse. The current negotiations began last year on the basis of an agreement between the parties: The Israelis would release 104 Palestinian prisoners, in four installments, and the Palestinians would hold off on plans to seek statehood recognition from international bodies. The arrangement was to last until April 29, by which time the goal was for at least a partial agreement that would keep the two sides talking.

But there’s been scant progress toward an agreement, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is refusing to release the fourth batch of Palestinian prisoners—which was supposed to happen by Monday. Netanyahu has no desire to set free people he sees as violent criminals only to see the talks peter out at the end of April, with nothing to show for the domestically unpopular action.

Enter Pollard. Leading Israelis and American Jews have long pressed for Pollard’s release. So have prominent non-Jewish national security figures, including George P. Shultz, who served as Secretary of State in the Reagan administration at the time Pollard was convicted, and Lawrence Korb, a former Regan assistant secretary of defense now at the liberal Center for American Progress, who argues that Pollard “has already served far too long for the crime for which he was convicted”—in part, Korb writes, because of a mistaken belief at the time of his sentencing that information he sold to Israeli had made its way to the Soviet Union.

Now it appears that Obama is dangling Pollard’s release as a means of persuading Netanyahu to make the final prisoner release, and perhaps to offer other concessions, including a potential settlement freeze, that would revitalize the talks.

To understand Obama’s calculation, it’s worth looking back at the last time a U.S. president seriously entertained Pollard’s release.

During the October 1998 Wye River Summit, Bill Clinton considered a request from Netanyahu—then serving his first of two stints at prime minister—to release Pollard in return for Israeli concessions to the Palestinians. Netanyahu told Clinton he needed Pollard’s release to appease the right wing of his political coalition, for whom Pollard’s release has long been a nationalistic cause (although Pollard has more recently won support across the Israeli political spectrum). Dennis Ross, who was then Clinton’s top Middle East negotiator later wrote in a memoir that he told the president Pollard was seen as a “soldier” for Israeli, adding that “there is an ethos in Israel that you never leave a soldier behind in the field.”

Ross, who went on to work for the Obama White House, also told Clinton that Pollard “had received a harsher sentence than others who had committed comparable crimes.” Still, Ross advised against tying Pollard’s release to an agreement, arguing that if Clinton were to do so, he should only use Pollard as a chit to seal a final peace agreement much later in the process.

Clinton pursued the idea anyway. What finally snuffed it was then-CIA Director George Tenet’s vow to resign. The New York Times reported that Tenet believed “he would lose his credibility with his rank-and-file in the intelligence community if he were to agree to Mr. Pollard’s release from his life sentence.” Clinton ultimately backed away from a Pollard deal.

In the end, Obama may do the same. After all, it can’t be any easier to grant clemency to a man convicted of espionage in the post-Edward Snowden world. And Dennis Ross might also apply his logic from 1998 to the present situation—arguing, perhaps, that the Pollard card is too important to play short of the very last push to a final agreement.

But there’s also evidence that, without some kind of dramatic U.S. intervention, the peace process will fail. That could dash any prospect for a foreign policy breakthrough in Obama’s presidency.

The question now is whether Obama decides the risk of releasing Jonathan Pollard outweighs the risk of watching the peace process die.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com