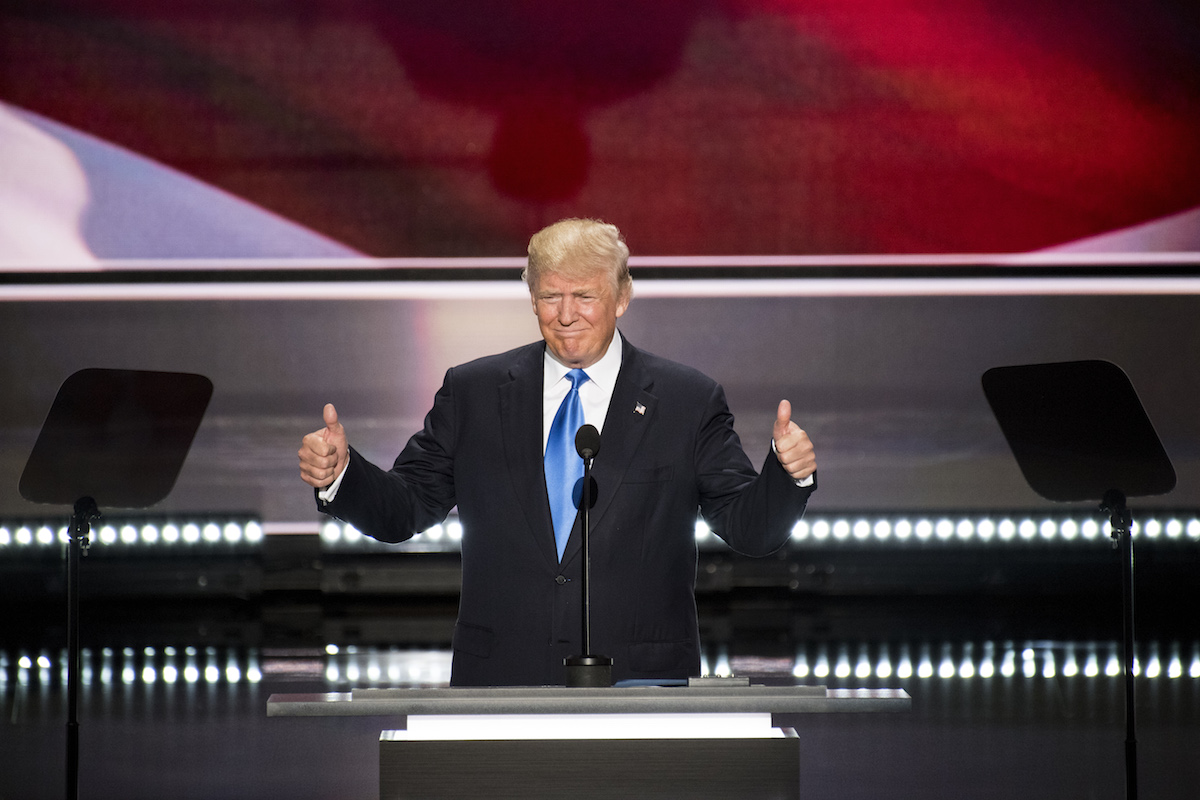

As Donald Trump prepares to celebrate his nomination as the Republican Party candidate for President with a speech on Thursday night at the party’s national convention in Cleveland, he will surely be looking forward, to November. But he’ll also be looking back.

Insiders on the Trump team have said that, in his speech and in general, Trump will be looking to a very specific moment in history: Richard Nixon‘s nomination in 1968. In particular, the New York Times reported on Monday that campaign chairman Paul Manafort had said that Trump planned to look to Nixon’s 1968 acceptance of the nomination for inspiration for his own such speech.

So, what does 1968 tell today’s political observers about what to expect on Thursday?

That late-’60s moment was one of great tumult in America: Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy had been killed that year, leaving both the civil-rights movement and the Democratic Party in turmoil. President Lyndon Johnson had decided not to seek reelection, declaring so in a speech that centered on the ongoing struggle in Vietnam. Protests roiled American campuses and popular culture only highlighted what many saw as a schism between the generations. Nixon’s task, then, was to position himself as a way out of all that.

“[Nixon] worked for two weeks on the speech, writing it out himself on yellow legal pads…” TIME reported in 1968, following the convention. “It was a mixture of carefully balanced political calculations and genuine personal warmth. It was, by any reasonable standard, corny, but it also was one of Nixon‘s most effective speeches in years. Gone was the excessive partisanship and professional anti-Communism of his early days. The nation wants a high-roader after Lyndon Johnson. The republic has survived subversion. The cold war is passé. Viet Nam is something to be settled, not won. So Nixon told them what they wanted to hear.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

If Nixon’s speech is any indication, “what they wanted to hear” was, first, a show of party unity. The future president opened the speech in Miami with a call back to President Eisenhower, and spoke of the party feeling that had come out of the convention. He praised his vanquished rivals and compared the Republicans’ post-primary unity with the feeling of division that had swept the nation under the previous White House administration.

They wanted their despair and alienation acknowledged. Nixon assessed the stakes of the election, asking a poignant question about the tumultuous state of the world at that moment: “Did we come all this way for this? Did American boys die in Normandy, and Korea, and in Valley Forge for this?” The question and its answer both came from the group that would be known as the silent majority, the people whom Nixon said were “the great majority of Americans, the forgotten Americans — the non-shouters; the non-demonstrators.” Those people, of all races and national backgrounds and ages, “give lift to the American Dream,” he said, and they were the reason for the nation’s glory. Those people were, he said, “the real voice of America.”

The nation’s recent leaders, Nixon believed, had not lived up to that greatness. From Vietnam to the economy to racial violence, he saw evidence that it was time for a change at the top. Though he was careful to specify that solutions would not come overnight, he promised honesty and action, beginning with an end to the war in Vietnam.

They wanted a return to what was painted as a rosy, calm and orderly past. An “honorable” end to the conflict, he continued, would be just one part of the mission to restore international respect for the United States. Looking to the American Revolution as an example, he judged that “the first requisite of progress is order” and promised to restore power to the courts, to law enforcement, to those who would fight the “merchants of crime and corruption in American society.” The “progress” side of that law-and-order promise was to reduce government programs like welfare and public housing while using tax policies to support American private enterprise.

And they wanted a hopeful vision of the future. In closing his speech, Nixon looked back to his own archetypal American boyhood and ahead to the American bicentennial and to the year 2000, summoning a vision of a future America on a day on which “our nation is at peace and the world is at peace.”

Perhaps most significantly, throughout this speech Nixon summoned an idea that will be familiar to Trump-watchers today—albeit in slightly different form. While Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan implies that the nation is not great at the moment, Nixon portrayed the greatness of the United States as enduring but obscured.

“My friends, America is a great nation,” Nixon said. “And it is time we started to act like a great nation around the world.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com