The letter to French President François Hollande was filled with seething anger—as well as a premonition that something ghastly might happen on the French Riviera.

In a four-page missive dated July 13, the region’s president and former mayor of Nice Christian Estrosi warned Hollande that the police force was ill-equipped to deal with terror threats, and less well-armed than would-be attackers. “It’s your responsibility to implement the emergency plan,” he wrote, in a letter leaked to Le Figaro after the attack. “We cannot afford to let ourselves think that the State would be outmatched.”

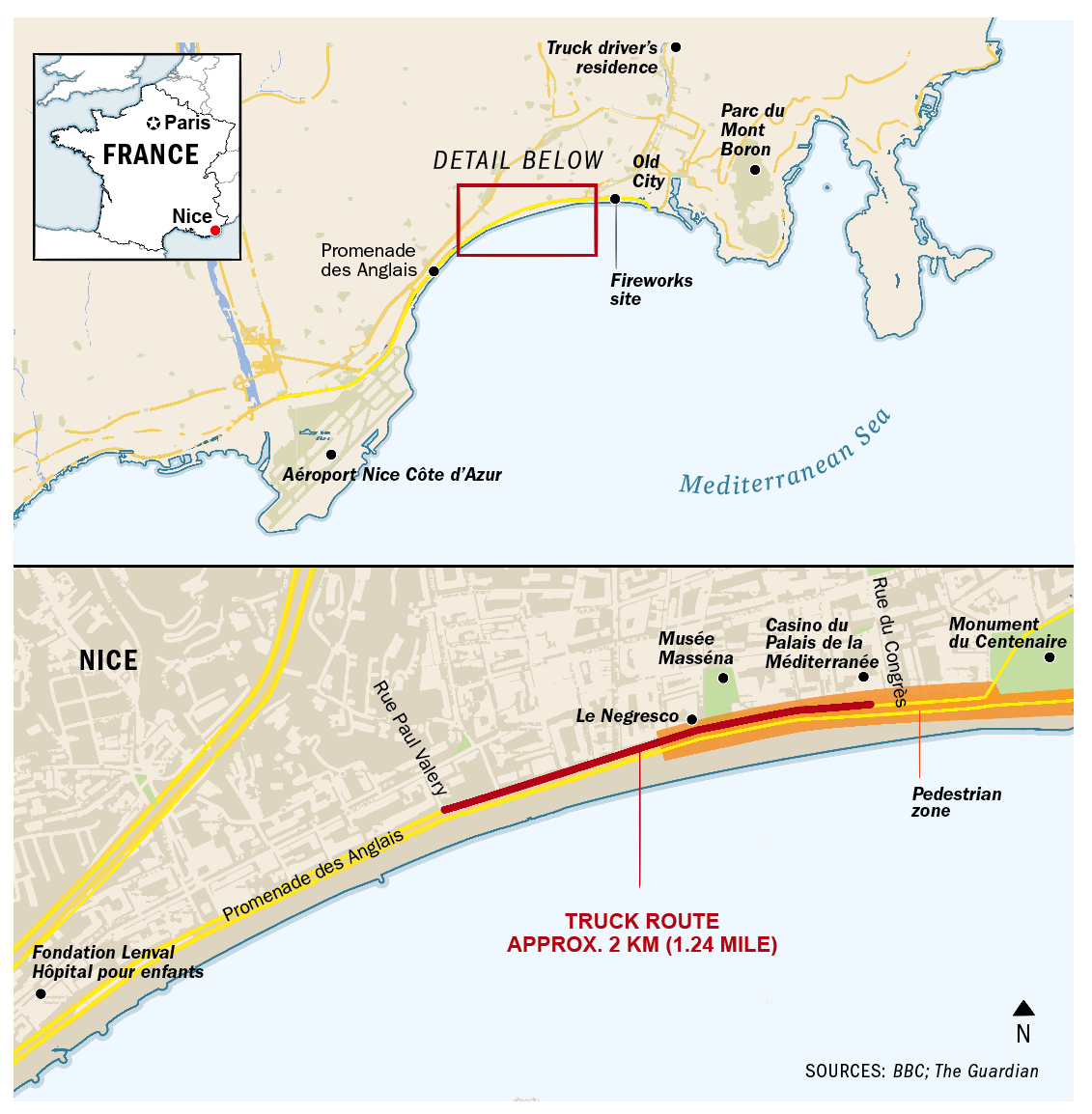

It took just one day to prove Estrosi’s point. Last Thursday, a truck driver plowed into Bastille Day crowds on Nice’s famed seafront, killing 84 and turning the waterfront Promenade des Anglais into a bloodbath. While there were hundreds of police on duty for the holiday fireworks display Thursday night, the driver nonetheless succeeded in mowing down people for 45 seconds over more than one mile, before police killed him in a blaze of gunfire. On Sunday, officials said the driver, Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, had sent a text message to an unnamed accomplice 15 minutes before the attack, saying, “send more weapons.”

As the investigation continues, a distressed country is beginning to train its anger on the deeply unpopular Hollande and his government. After three major attacks in France over the past 18 months, many French see their leaders as impotent against an enemy they have been unable to root out.

“This a big trauma,” says Rudy Salles, a Deputy Mayor of Nice for the center right Nouveau Centre party standing on Nice’s seaside promenade amid flowers and candles left by residents. He told TIME he believes the government has done too little to protect the country. “The first terror attack, okay. The second terror attack, okay. The third terror attack—we want action,” he said.

But on Sunday, French Prime Minister Manuel Valls admitted there was no quick answer. “There will be more attacks,” he said in an interview with Journal du Dimanche. “This is difficult to say, but other lives will be lost… Terrorism will be a part of our daily lives for a long time.”

This will be of little comfort to a populace still reeling from the attack. As devastated relatives begin burying their loved ones, including at least 10 children, the moment of mourning risks descending into a fraught argument over what to do — and who is equipped to do it.

In stark contrast to the giant march in Paris after the Charlie Hebdo massacre in January 2015, and the enormous outpouring of public grief after the November Paris attacks, last week’s attack in Nice has brought divisions into the open between people of different political views, and even within the government itself, over how to dismantle terrorism.

Salles says that the government appeared to let its guard down just before the Nice attack, after hugely increasing security for the month-long European Football Championships that ended on July 10. He claims there were fewer police on duty in Nice for Bastille Day, he said, than during those tournament matches or during the Nice Carnival last February. “There was a kind of sentiment of lightness,” he said.

If so, that sentiment vanished the moment of the Nice attack. An ashen-faced Hollande declared he would extend France’s state of emergency, imposed last November, for at least three months, reversing a decision he’d announced just hours before the Nice attack. And he called on “patriotic French” to volunteer for the civilian military reserve.

But the French are skeptical, believing that beefing up the police presence won’t change anything; after all, thousands of armed soldiers and police have patrolled public sites since the Paris attacks eight months ago. If that did not work, what will?

“The problem we are facing is increasingly individuals or micro-cells carrying out terrorist attacks,” says Jean-Charles Brisard, chairman of the Center for the Analysis of Terrorism in Paris, who participated in a government inquiry into anti-terrorist strategies after the Paris attacks. “Those are very difficult to detect.”

In yet another sign that the devastating Nice attack is now a divisive political issue, Valls expressed little sympathy for the French Riviera leader’s plea to Hollande for a better-equipped police force. “If Christian Estrosi had the slightest doubt, he could have asked for the cancelation of the fireworks,” Valls said. Estrosi is a member of the rival Les Republicains party.

Like Valls, Brisard believes France will need to live with terrorist threats for years to come, based on the fact that at least 600 French citizens are believed to still be among jihadist forces in Syria and Iraq, and that about 400 children are also there, many of them born in those countries, according to him. “The ideology of jihadism is deeply entrenched in France. To eradicate that ideology will take generations,” he told TIME on Sunday.

Some of the criticisms against the government are rooted in the fact that a fierce battle is underway to replace the widely disliked Hollande in presidential elections next April. Hollande’s ratings fell to a rock-bottom 12% last month, and the Nice attack could hurt him further.

Presidential contenders have seized on the Nice attack to burnish their anti-terrorism credentials. Former president Nicolas Sarkozy, who is weighing running again next year for the right-wing Republicains, said on French television on Sunday night that those with links to terrorist groups should be stripped of their French nationality—a hotly debated issue among French politicians. “Someone who shoots at French people, someone who kills, someone who wants to jihad, does not have a place in France,” he said.

On Saturday the far-right National Front leader Marine le Pen told reporters the Nice attack was “the fault of a state, failing in its first priority, which is the protection of our country.”

In a France plagued by fear uncertainty, one thing is becoming increasingly clear – in next year’s elections, the terror attacks will be front and center.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com