Presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump was saying what a lot of Americans were probably thinking following the latest terror attack when he said it is time to declare war on the Islamic State. “I would,” Trump said when asked on Fox News shortly after the attack if he would seek a declaration of war on ISIS. “This is war. If you look at it, this is war.”

There is a certain logic to his urge following the French truck massacre that killed at least 84. ISIS surely is at war with France, the U.S. and much of the rest of the civilized world, and it seems only fair to return the favor as the bloody scenes from Nice flood our minds (ISIS hasn’t yet claimed responsibility for the attack, although this is becoming a distinction without a difference as lone-wolf attacks increasingly seem to be taking inspiration, if not direct orders and support, from the Islamic State).

Declaring war would certainly be cathartic, politically, for a nation that has lived in the shadow of Islamic jihadists since September 11, 2001. But such a declaration is a hammer that views the problem it wants solved as a nail. While military action is required beat ISIS, it won’t be sufficient.

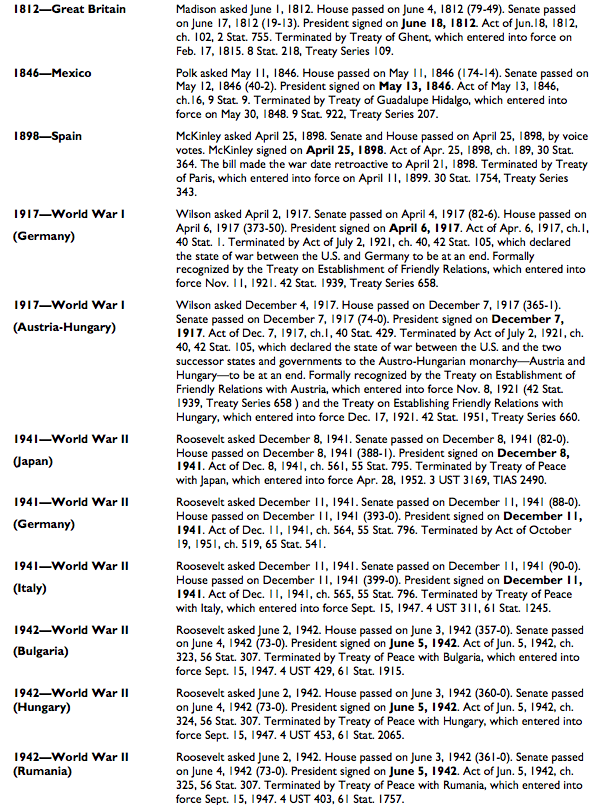

It’s worth noting that a President—even a President Trump—can’t declare war. The Constitution limits the power “to declare War” to Congress in its Article I, Section 8. It’s a power that has grown rusty from disuse: Congress has declared war only 11 times, mostly recently six times during World War II (separate declarations in 1941 and 1942 against Japan, Germany, Italy, Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania, see right).

Congress has been content to sit on its hands since the U.S. began bombing ISIS targets two years ago. Lawmakers essentially have washed their hands of responsibility, letting President Obama attack ISIS under authority a long-ago Congress gave President George W. Bush to strike al Qaeda within a week of 9/11.

The lack of formal congressional support bothers many in the U.S. military, who see it as evidence of politicians willing to send them into combat without the grit of ordering it. “Members of Congress have chosen to avoid a vote on the theory that either a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’ vote carries political risk,” Sen. Tim Kaine, a Virginia Democrat believed to be on Hillary Clinton’s short list of vice-presidential candidates, said last month. Kaine, who has a son in the Marine Corps, said it is “immoral to continue sending Americans into war if we are unwilling to vote to support that war.”

There would be other benefits of declaring war—or at least a debate over doing so. Such a clarifying debate among senators and representatives would illuminate divisions within the country about its wisdom. No matter what Congress decided, such a debate and resulting vote would reveal how far the nation is willing to go to fight the ISIS threat. That bright, shining line would be welcomed by the U.S. military, U.S. allies and the U.S. public (apparently the only ones eager to shield their eyes from such a declaration are the brave members of the U.S. Congress).

Militarily, a war declaration wouldn’t mean U.S. troops would suddenly find themselves parachuting into Raqqa to hunt down and kill ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his war council. Given its proto-state status, removing the shrinking sanctuaries ISIS still has in Iraq and Syria would likely be only the first step in a journey toward ridding the world of its hateful ideology. But it would signal an American determination to prevail in a way that doesn’t currently exist. Obama’s eagerness to pull U.S. troops out of Afghanistan and Iraq before their task was finished—Congress can’t complain too much, given that it has been MIA on the topic for years—has highlighted the fecklessness of that approach.

Crippling, if not defeating, ISIS is likely to take decades. Any stepped-up move to wipe out ISIS’s self-declared caliphate would mean more civilian casualties. Such deaths—despite U.S. efforts to avoid them—are a rallying cry for ISIS supporters. They say they are only killing civilians in Europe and the U.S. to retaliate for Muslim civilians killed by errant U.S drone strikes and other battlefield error (somehow, the fact that ISIS has killed far more innocent Muslims than the anti-ISIS coalition arrayed against it gets overlooked in the jihadists’ fervor).

The current strategy of U.S.-led air strikes and training local armies on the ground is slowly bearing fruit as the territory held by the Islamic State shrinks (more certainly could be done: through March, the number of weapons used against ISIS peaked at 3,227 last November, and dropped to 1,982 in March—a decline of nearly 40%.) The length of time that is taking to defeat the Islamic State helps embolden faraway would-be jihadists, lone wolves or otherwise, to strike far from Raqqa to prove their support of the melting caliphate.

U.S. officials have long predicted that as the U.S.-led alliance squeezes ISIS, such attacks are likely to increase. “We are not going about stopping the influence of the Islamic State in the right way,” argues David Deptula, a retired Air Force lieutenant general who commanded the air war over Afghanistan following the 2001 U.S. invasion. “Not assembling a strategy and associated campaign to rapidly halt the Islamic State’s ability to function as an organization; taking a gradualistic approach instead; and employing an anemic application of force relative to previous air campaigns, has yielded the Islamic State time to export their message, garner followers, and spread their message.” Over the past day, the Pentagon said it had carried out 18 airstrikes against ISIS targets, including one that destroyed an ISIS vehicle. But no military campaign, no matter how crafty, could have destroyed that single large white truck in Nice.

Waging war on ISIS, declared or otherwise, isn’t war on an industrial scale. It will rely on U.S. air power, including drones, and U.S. Special Forces, moving steadily toward the front lines alongside local fighters, to help grind ISIS into history. It’s unlikely to result in carpet-bombing, or massed allied tank armies plunging wholesale into Raqqa. It’s also unlikely that al-Baghdadi, facing sure defeat, would kill himself in a bunker as Adolf Hitler did. And ISIS will never sign instruments of surrender aboard a hulking U.S. warship, as Japan did to end World War II.

An ideology, unlike a conventional military power with the infrastructure of a state behind it, can’t be bombed into submission. After the final bombs are dropped on Raqqa and ISIS leaders are dead, some of the embers the Islamic State has spewed across the globe will keep smoldering. Sure, the oxygen that the caliphate provided would-be jihadists around the world will disappear. But those cinders will keep glowing, all but unseen, waiting for the right moment to explode into flame. Trump acknowledged, almost in passing, as much Thursday night. “It only takes one or two people,” he also told Fox, “to create havoc.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com