Do you have a question about history? Send us your question at history@time .com and you might find your answer in a future edition of Now You Know.

Today, a man—or a woman—wearing long pants to a formal occasion is nothing special, and being able to easily distinguish a man’s sock color is not the norm. But it wasn’t always that way. Case in point: George Washington and America’s other founding fathers are not wearing pants in the portraits from which we remember them. They’re wearing knee breeches and stockings.

Longer trousers, or pantaloons as they were sometimes called, took decades to gain acceptance in the U.S., as they became the norm for first the working classes and eventually for the wealthy. As is often the case, there was a not-so-subtle message behind the fashion: as Teresa Teixeira, an assistant curator at James Madison’s Montpelier home, explains, trousers were “much better for movement than your really tight breeches, which were really tight. The reason they were so tight was because then you can show off, ‘Well, I clearly can’t work in these.'” People who did have to work for a living wore pants for practical reasons, and the style grew in Europe before it made its way across the Atlantic. During the French Revolution the sans-culottes movement promoted (among other things) the style of pants worn by the lower classes, instead of the impractical breeches of the upper class.

Such a shift in clothing style didn’t happen for everyone in a single moment. Linda Baumgarten, curator of textiles and costumes at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, says a number of factors influenced who wore trousers and when, from social class to the occasion in question. “Presidents,” she says, “have to dress according to their status and their belief system.” It’s unlikely for the latest trend show up in a president’s official wardrobe, and that’s particularly true for the early presidents, who had to convince the world that the U.S. was a nation worthy of respect.

And, while James Madison often gets credit for being the first president to make the switch, historians say it’s unlikely he would have worn long trousers.

Madison was “always noted for looking very old fashioned, so he probably didn’t adopt long trousers” says Teixeira, nothing that pants were just beginning to make their way into fashion during his presidency. Even late in Madison’s life observers commented on his breeches. He was described as wearing, at age 85, “black cloth pantaloons extending only to the knees.” In 1863, years after Madison’s death, his slave and manservant Paul Jennings described him as “always dressed wholly in black — coat, breeches, and silk stockings, with buckles in his shoes and breeches.” Though Madison appears to have bought a few pairs of pantaloons in his day, they were for his adopted son from Dolley Madison’s first marriage, judging by school receipts.

Though Madison did sometimes make a splash with his outfits (he wore all domestically produced cloth to his inauguration, encouraging support of U.S.-made goods), both John Stagg, editor in chief of the Papers of James Madison, and Madison biographer Ralph Ketcham told TIME they would be surprised if Madison had worn trousers, either while president or after.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

So if not Madison, who?

It’s not likely to have been an earlier president: George Washington was too early, and though Thomas Jefferson spent time in France, during his administration pants would have been considered far too informal for the office. Though there is evidence that Jefferson purchased pantaloons in the spring of 1801, Baumgarten says there’s evidence those were for his servants. In fact, firsthand descriptions of Jefferson note his stockings, which wouldn’t have been visible if he were wearing long trousers. While Jefferson was once described wearing pants in 1822, that was well after he left office. Meanwhile, Madison’s immediate successor, James Monroe, was known for being old-fashioned, favoring knee breeches. (The James Monroe Museum, after this article was originally published, commented that Monroe had at least once in 1817 been observed wearing pantaloons while riding, but he wasn’t known for it.)

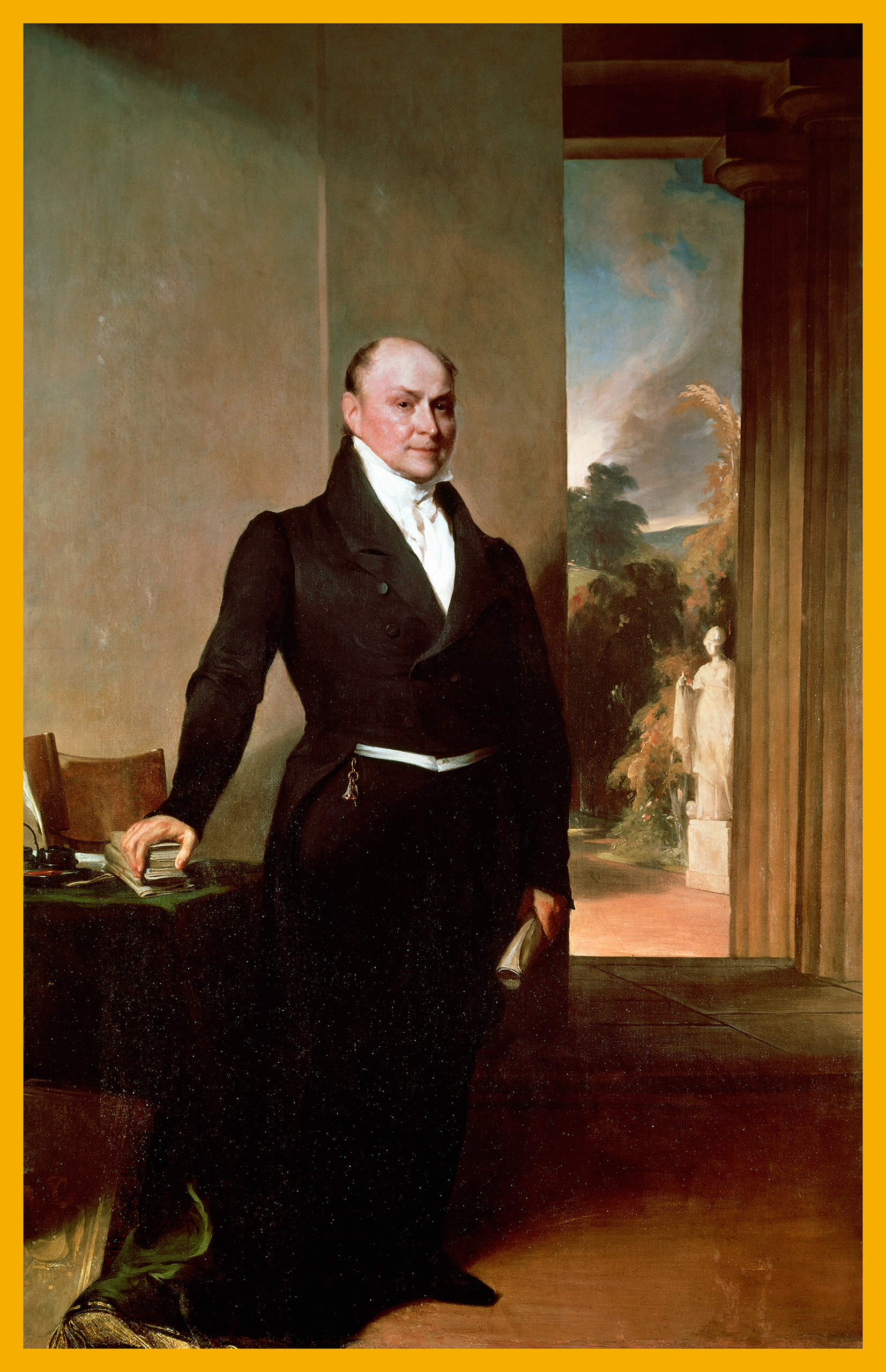

That means John Quincy Adams was likely the first sitting President to wear long pants for any presidential occasion. The Senate committee on inaugural ceremonies website reports that he wore a black homespun suit with long trousers to his inauguration on March 4, 1825.

The evidence behind that description is all anecdotal, notes Jessica Pilkington of the Adams National Historical Park, but even so, JQA does seem to have worn trousers during his time a president. A portrait from his time in office shows Adams wearing knee breeches, capturing a time of fashion transition, but in the fall of 1825, Adams was insistent that he should be shown in a different official portrait wearing “plain American dress”—meaning “plain black pantaloons and boots under them.” The resulting picture above was painted in part by Gilbert Stuart and completed by Thomas Sully. Stuart and Adams’ father were both strongly against such attire for the image, but Stuart died before completing the portrait and Sully went along with the younger Adams’ wishes. And he must have been known for those desires: a political cartoon from 1824 shows Adams in trousers, among a crowd of people in breeches.

Teixeira adds, while that Adams could have picked up the fashion during his travels in Europe, the reason he wore pants “probably also had to do with associating himself with working Americans, because by that point America was putting itself out as an industrial country.”

After Adams, though breeches didn’t disappear entirely, especially for more formal occasions, pants had made it big. After all, as Baumgarten points out, Adams himself proved pants were O.K.: the anecdotes about Adams wearing long pants, she says, “even in that kind of formal occasion, meant they were pretty generally accepted by 1825 when he was inaugurated.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com