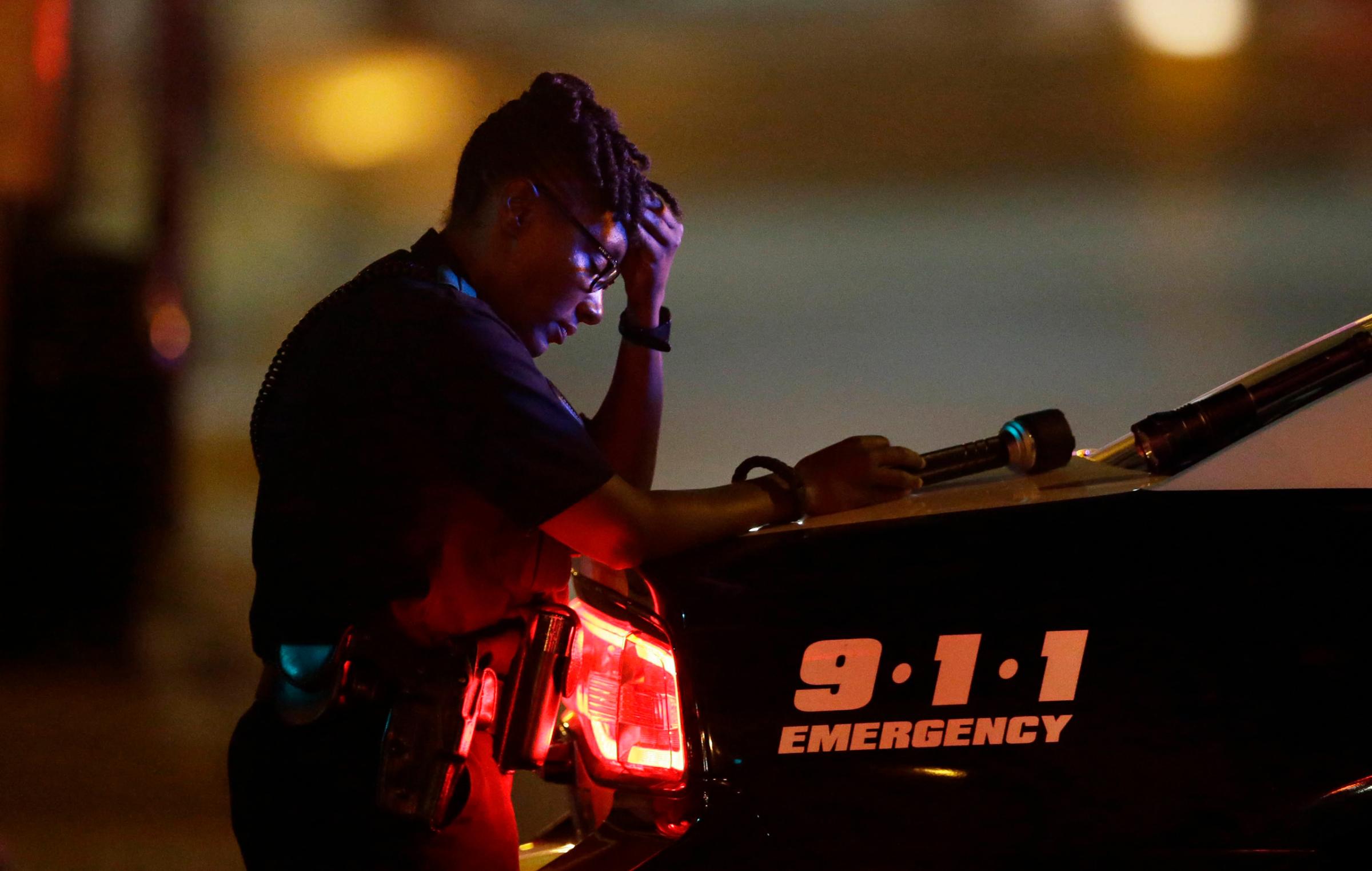

Police are trained to deal with fast-moving situations. But the events of the last 72 hours—first the surging uproar over the shooting deaths of young black men by officers in Louisiana and Minnesota, then the assassination of five officers in Dallas—have officers across the country struggling to find their footing in a place none of us has quite been before.

“It’s a weird haze over all of us. It’s bizarre,” says Capt. Joe Bologna, who oversees policing in the 19th District of Philadelphia, a largely poor and African-American precinct in the city’s west side. The 19th was where I spent a few weeks a year ago, reporting the TIME cover story: “What It’s Like To Be A Cop In America.” The one-word answer at the time, a year after Ferguson, Mo., was “harder.” On Friday, a second word applied: “strange.” The Dallas attack on officers while guarding an anti-violence march critical of police had added a disorienting new layer to everything. The next morning, the Philadelphia department suspended single patrols; every officer goes out with a partner, no exceptions.

“It gives them somebody to talk to in the car, just to express their thoughts or something,” says Bologna. “We don’t want them solitary in the car, things just running through their minds. It’s good to have a partner. It just helps them get over it. You internalize that, it ain’t good.”

“We want to make a difference. And all this other stuff clouds all that. And I don’t want these guys to think what they do doesn’t matter; because it does. They change people’s lives.”

Five Officers Dead after Gunmen Open Fire at Protest in Dallas

The striking thing, at least in Philly, was how many people were reaching out to reassure passing cops. “Believe it or not, I feel more support,” says Brian Dillard, an African-American officer who grew up in the district, and spoke by phone from patrol. “People are saying, ‘Have a good day,’ ‘Be safe out there.’ ‘Be careful.'”

Bologna was getting the same, in the form of text messages: “Stay safe.” “We support you.” On a day when thousands turned out for a prayer service in downtown Dallas honoring the slain officers, the messages in gritty West Philly reflected two foundational realities: One was the compact between society and the men and women sworn to protect it. The other, more complex but ultimately logical reality was one also captured by polls: Black Americans are at once more likely to report unfair treatment by police—and more likely to seek a greater police presence in their own neighborhood. In short, where crime is a problem, more policing of any kind—even imperfect—is better than less.

“A lot of people, I’m pretty sure they calmed down a little after what happened in Dallas,” says Mischel Matos, one of two officers pictured on the TIME cover, who reports relatively little negativity coming his way. The more persistent problem, Matos says, is that people see the uniform but not the person inside it. “Usually everybody’s saying, ‘Oh, every cop they just want to do this.’ People think every cop’s the same. But we’re not.”

It’s a version of the same complaint that African-Americans have placed before law enforcement, of course, and not without profound and historical justification. But by training and necessity, police tend to think tactically, addressing the problem right in front of them and getting on with the job, which is hardest in the neighborhoods that others take pains to avoid.

“People say, ‘You’re biased to everybody.’ Well, you’re doing the same things to cops,” says Bologna. “It goes back to what my father used to day: two wrongs don’t make a right.

“We’re getting persecuted,” he continued. “That’s what we expect. We’re cops. But that works on their psyche. I’m working on their psyche the other way. We don’t want to get them into a mentality that everybody’s against them. It’s not true. It’s so not true.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com