Odds are, you never take a moment to say thank you to Jupiter—but it’s not too late to start. The fact is, if the fifth planet from the sun weren’t here, there’s at least a fair chance that the third one (that would be Earth) wouldn’t be either.

Jupiter is not only the biggest planet in the solar system, it’s also the one with the most powerful gravity. For billions of years, it has thus stood as a sort of guardian over the smaller planets of the inner solar system, pulling in and gobbling up comets and asteroids as they fly by. Certainly, it hasn’t caught all of them—the moon didn’t get those craters by accident—but it’s gotten plenty, and that matters. You know that asteroid that killed the dinosaurs? Imagine if Earth got clobbered like that all the time.

That’s just one of the things that makes Jupiter a world that deserves our attention. And it’s about to get a lot of it, when NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which left Earth on Aug. 5, 2011, arrives at Jupiter at 11:35 p.m. EST on July 4, beginning what is planned to be a nearly 20-month mission. (TIME will carry the arrival live.)

Juno’s final approach to the planet is actually already underway, having started on June 30, when the ship powered up its instruments and positioned itself for a 35-minute engine burn on Independence Day evening—a bit of fireworks that will be a lot more complicated than the ones that will be taking place all over the U.S. at the very same moment. The maneuver will slow the ship by 1,212 mph (1,950 k/h) from its current speed of over 16,000 mph (25,800 k/h), just enough to settle it into orbit around Jupiter.

The spacecraft will inscribe what is known as a polar orbit, circling the planet not more or less horizontally as most satellites do, but north to south, pole to pole. That will allow it to survey the entirety of Jupiter as it rotates slowly beneath. Juno’s first few orbits will be high-altitude ones, each taking 53.5 days to complete. But another engine burn will lower it to as close as just 2,600 mi. (4,200 km) above the Jovian cloud-tops, making for a zippier 14-day trip around the planet. There will be a lot to study from that close-up perch.

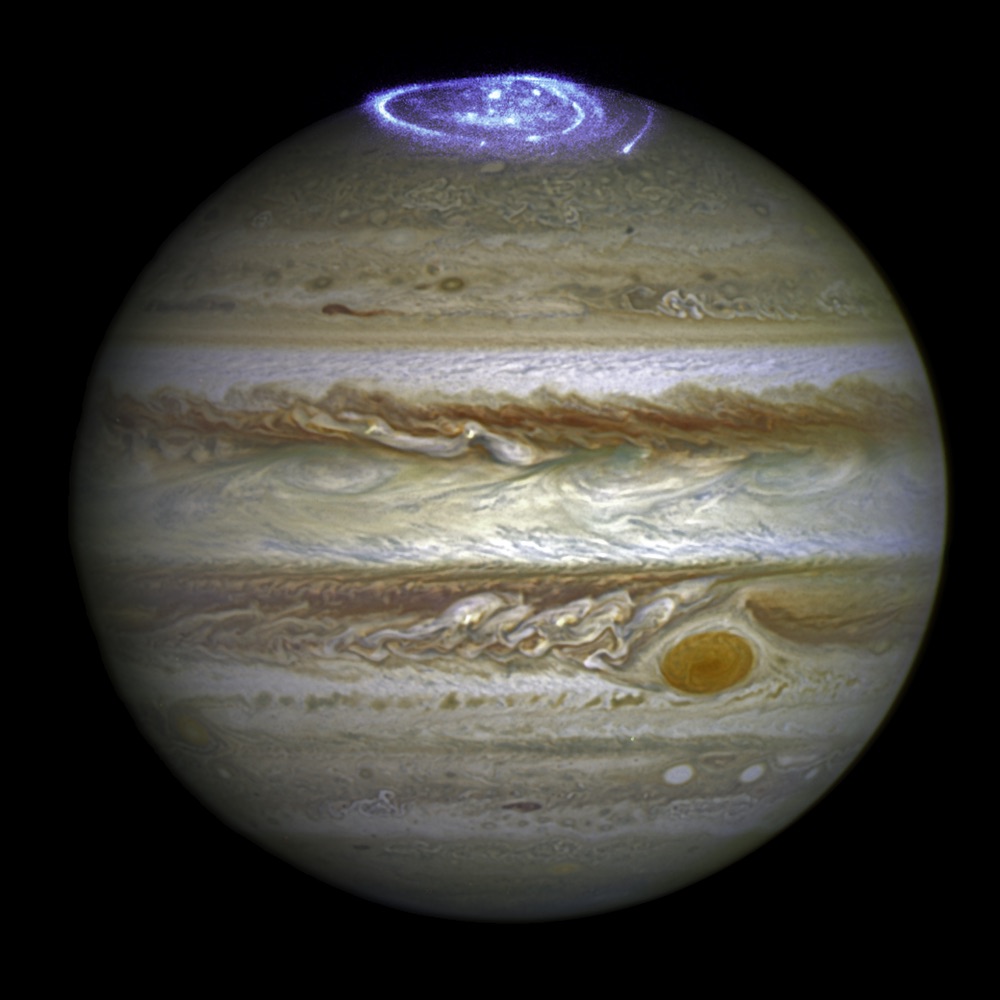

Jupiter is often thought of as a sort of failed star, with a hydrogen-helium mix similar to that of the sun but without the mass to get its stellar fires lit. Still, its radiation field is so powerful that it is the only planet in the solar system that actually emits more energy into space than it absorbs from the sun. Jupiter is a place too where liquid helium falls through the clouds like rain; where hydrogen is subjected to such pressures that it behaves like an electricity-conducting metal; where the temperatures are just 152º F (67º C) on the surface but 62,000º F (34,000º C) below the clouds.

All that and more will be studied by a suite of nine instruments that will investigate Jupiter’s gravity, radiation field, atmospheric chemistry, aurorae, magnetism and other vital signs. The spacecraft will also capture—and send home—an album’s worth of dazzling images.

When the last bit of data has been streamed to Earth, in February 2018, and the 37th of Juno’s allotted orbits is done, it will light its engine just once more, this time to send it on a suicide plunge into the boiling atmosphere of the planet. It will have given its life for a good reason.

Jupiter is parent to 62 known moons, four of which—Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto—are large enough to have been discovered by the comparatively primitive telescope of Galileo Galilei in 1610. Europa in particular holds fascination for astronomers because it is thought to have a realistic chance of harboring life, thanks to a comparatively warm, globe-girdling ocean beneath a rind of ice. Spacecraft sent from Earth can harbor terrestrial microorganisms, which could lead to biological contamination if Juno were left to die in orbit and it wandered into a collision with Europa. Two of the other so-called Galilean moons—Callisto and Ganymede—are also considered candidates for buried oceans, and also deserving of protection.

So tantalizing is the potential of Jupiter’s moons that Juno is carrying a plaque etched with the words of—and in the hand of—Galileo himself, as he recorded the discovery of the moons in his notebook. At the time, he knew of only three of them and wrote, in part, “…it is evident that around Jupiter there are three moving stars invisible till this time to everyone.”

Those “stars” are visible now. And the planet they orbit will soon be far more visible still. Galileo’s work, begun more than four centuries ago, goes on this summer.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com