A curiously old-fashioned aura surrounds the latest account of serious wrongdoing in the New York City Police Department: As Preet Bharara, the U.S. Attorney in Manhattan who brought charges against three police officers told a news conference, the Brooklyn businessmen who allegedly lavished money and favors on them wanted “a private police force for themselves and their friends.” And, though New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio has not been implicated, the businessmen are also noteworthy for their ties to his fundraising efforts. Both Jeremiah Reichberg, who was indicted, and his friend Jona S. Rechnitz, who pleaded guilty and cooperated with investigators, have been staunch de Blasio supporters.

This newest disgrace is rooted in the oldest problem facing the force, one dating back to its creation in the 1840s.

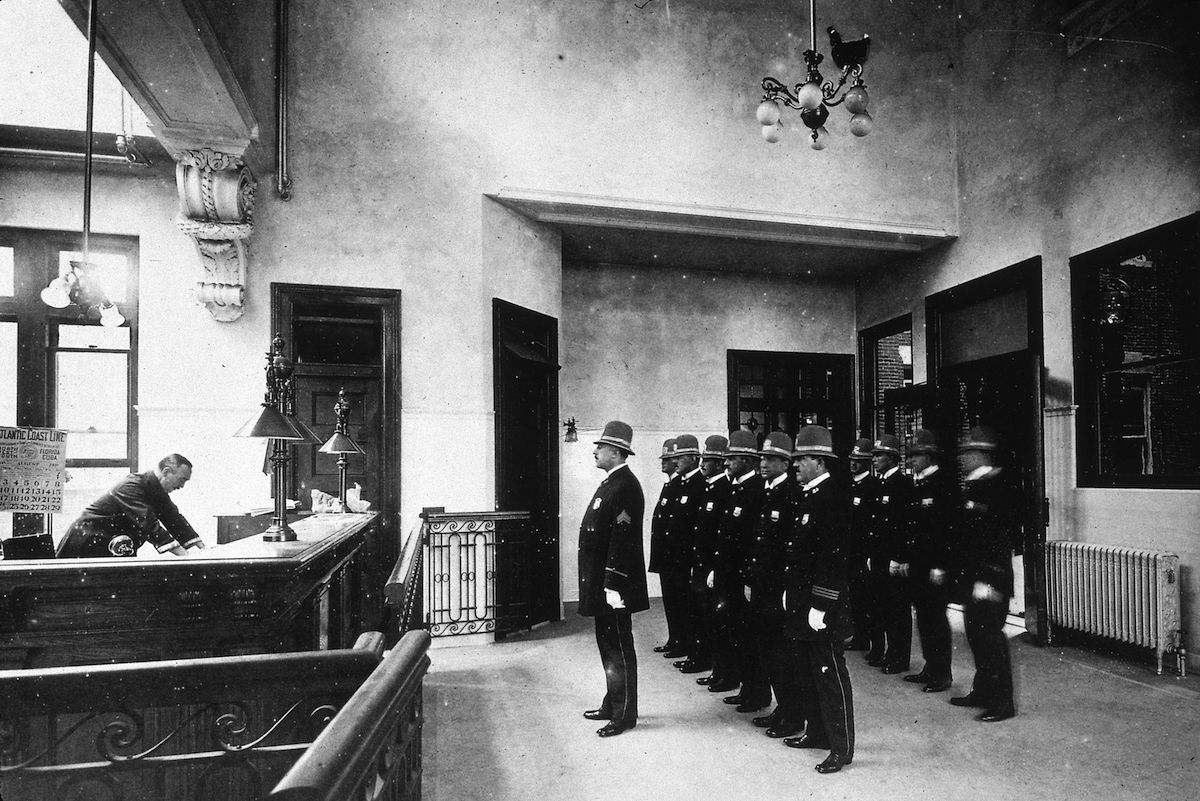

New York City established America’s first professional police force in 1845. The force was shaped from the beginning by distinctively American notions about limiting government power, distrust of a standing army and belief that municipal institutions should be close to the people. The city’s first police were appointed for one-year terms, nominated by the aldermen in whose wards they served. Because police were constantly angling for appointments and promotions from elected officials, partisan wrangling shaped the force from the very start. And the entrepreneurial element of police work that had been present from the colonial era expanded with the 19th century growth of the city. Police collected fees for serving warrants, detaining suspects and appearing in court. Detectives often received rewards for reclaiming stolen property and the police routinely provided special services for citizens and businesses. The boundaries between legitimate police work and amenities for those with political “pull” became very blurry.

In 1894 the New York State Senate launched the first comprehensive investigation of corruption in the NYPD. The so-called Lexow Committee revealed to the city and nation in unprecedented detail just how deeply entangled the NYPD had become in managing and profiting from the city’s vice economy. Police captains ruled their precincts like private fiefdoms, but appointment to command required money and political influence. The going price for a captain’s appointment, the investigation revealed, was $15,000 (roughly $400,000 today), raised from friends who expected favors in return. Regular payments poured in from brothel keepers, counterfeiters, saloon-keepers, gamblers and others in the city’s demimonde.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Police commanders also made lucrative connections with the city’s business elite. Superintendent Thomas Byrnes, who led the force after a long career as Chief of Detectives, testified matter-of-factly that his personal wealth was about $350,000, or $9.6 million today. Where did he get it? From investments made for him by Cornelius Vanderbilt and Jay Gould, both of whom had received special services from Byrnes. Indeed, the Gilded Age NYPD regularly engaged in the ruthless, often brutal, suppression of unions and political dissent. The city’s stockbrokers, bankers, real estate developers, merchants and hoteliers cared little about police corruption as long as the cops kept their boots firmly on the neck of organized labor and radical activists.

The current police scandal does not seem to indicate a deeper systemic pattern of venality as was revealed in the corruption investigations by the Mollen Commission of the 1990s or the Knapp Commission in the 1970s. (The latter made Detective Frank Serpico, played by Al Pacino in the Hollywood film, a household name and heroic symbol for reformers.) Nonetheless it reminds us that the mutual attraction between police authority and business influence means the threat of corruption and abuse of power is always present. The NYPD today is a much larger, more professional, and better-trained organization than it was in the 1890s. Now, as then, the great majority of police are dedicated civil servants rather than crooked predators.

Yet the potential for bribery, abuse of power and influence peddling cannot ever be totally eliminated. Preet Bharara’s aggressive efforts may prove the exception to a stubborn historical dynamic: the extreme reluctance of prosecutors and grand juries to punish cops, with whom they work so closely. History tells us that the successful prosecution of corrupt cops is both rare and nearly always a long and drawn out affair. In the aftermath of the Lexow investigation some 40 police officers, including an inspector and 14 captains (nearly half the department total) faced indictments on charges of bribery, extortion and neglect of duty. Yet by 1898, not a single New York police official was in jail and all the men dismissed from the force had won reinstatement with back pay through court appeals.

It’s too early to tell where this case might go. As a news story, it may not have legs. But the history surely does.

Daniel Czitrom is a Professor of History at Mount Holyoke College with a special focus on the history of New York City. He served as the historical advisor for the BBC America show “Copper” and is the author of New York Exposed: The Gilded Age Police Scandal that Launched the Progressive Era.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com