Being a feminist in 2016 is a strange thing. You are at once riding the wave of a radical social movement turned trendy (Beyoncé dancing in front of a flashing Feminist sign, Taylor Swift declaring her bona fides) and watching as the political realm struggles to keep up with, or actively tries to smack down, women’s progress (a renewed interest in federally funded child care but also unprecedented restrictions on women’s health care). The most serious female contender for the White House is facing off against an opponent running on intransigent masculinity; she still answers for her husband’s behavior, while he complains about women playing “the woman’s card” with his third, decades-younger wife standing at his side. Who uses which bathroom is suddenly a matter of great political concern. Abortion is back before the Supreme Court.

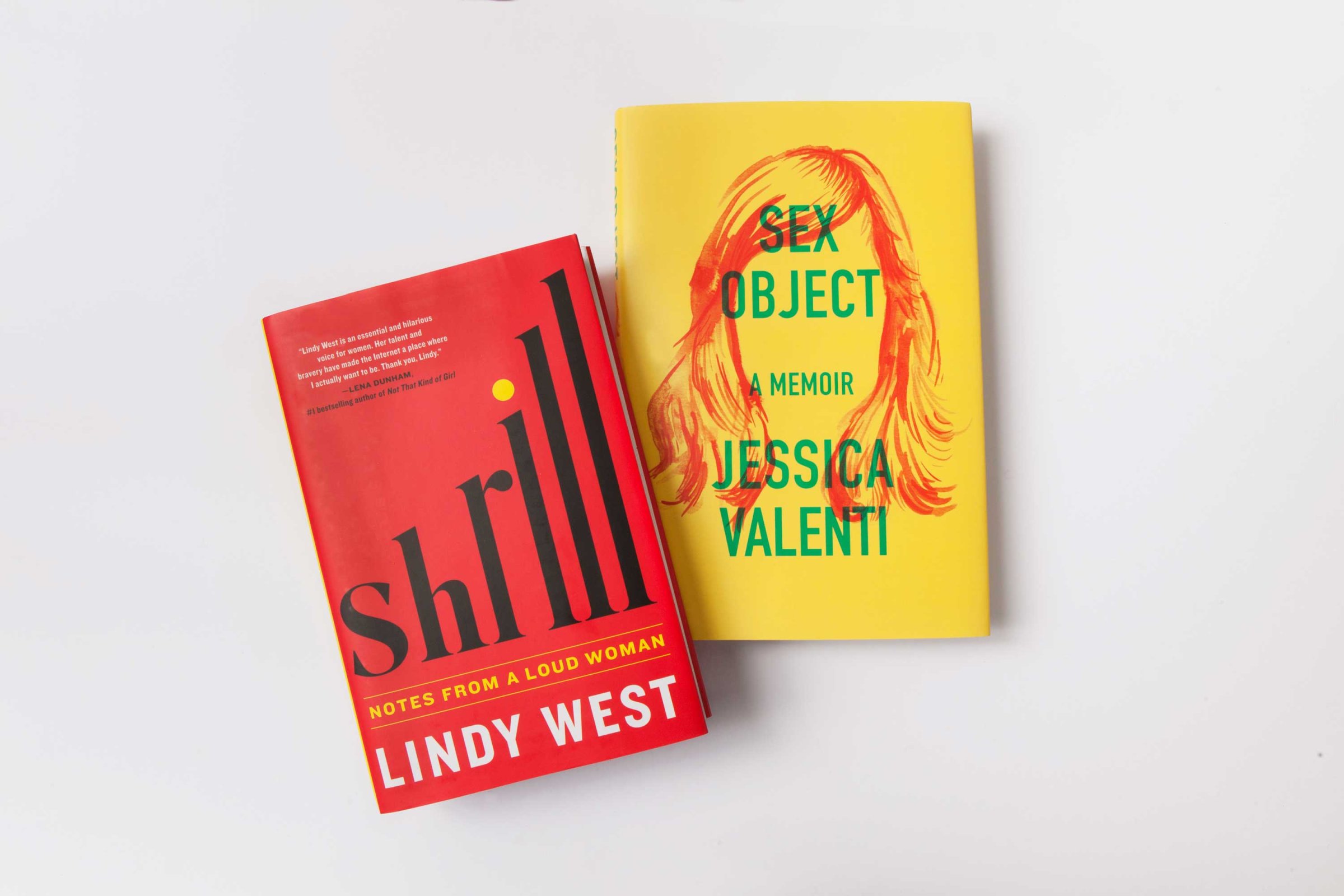

Thus, feminism itself is enjoying a resurgence, spurred on by young feminist writers. Two of those writers, Jessica Valenti, a founder of Feministing.com and now a columnist at the Guardian, and Lindy West, formerly of the blog Jezebel and now also at the Guardian, recently published memoirs: Sex Object by Valenti and Shrill: Notes From a Loud Woman by West.

Full disclosure: Valenti is a friend, and West is someone I’ve interviewed. Fuller disclosure: when I heard they were both writing memoirs, my initial reaction was to wonder why the world needed another memoir from someone who, I hoped, had not lived even half her life yet. (Valenti is 37 and West 34.) I should have been more generous.

There’s a power in reading these books together, at this moment in the culture, to see how the same sexist roots can grow different weeds. Both West and Valenti are harassed, objectified, treated as if their presence is an invitation for men to evaluate them as sexual goods, but their experiences play out differently. As a teenager, Valenti encounters men who masturbate on her in the subway; West has men tell her she’s too fat to rape. Both women grow up in a world that wants them to be small and quiet, and both refuse. For both, that privilege comes at a personal cost.

In Shrill, West writes in the same comic voice that brought her legions of fans at Jezebel. It’s a joke-a-sentence pace, tinged with West’s dismay at the hate she endures both for her work and for her body. “When I looked in the mirror, I could never understand what was supposedly so disgusting,” she writes. “I knew I was smart, funny, talented, social, kind–why wasn’t that enough?” Her humor is both a tool to promote her feminism and a shield against the blowback, but that tone starts to flag at the end when she writes about the abuse that came after she criticized rape jokes in comedy. When comic peers failed to stand by her side, West’s crushing disappointment breaks through her jokey tenor, showing the myriad ways a sexist culture squelches even the brightest women.

In Sex Object, that flattening is obvious from the get-go, and the sardonic voice Valenti cultivated as a blogger is nowhere to be found, replaced by frustration-tinged sincerity and sometimes just sadness. Reading anecdotes of how people, mostly men, tried to make Valenti’s existence dimmer was both illuminating and draining–and on a very human level made me exceptionally sad for my bighearted, vivid friend and women like her.

Notably, both women write about their abortions, both without regret but with a complexity of emotion often absent in politicized battles. Both note the importance of being able to make that particular choice at that particular time—how ending a pregnancy kept so many doors open. For Valenti, “The abortion marked the last in a succession of decisions to take hold of a life that was increasingly careening out of control”; after it came the publication of her first book, the end of a drug habit, meeting the man she would marry, having her daughter. West, too, made great professional and personal strides because she chose not to become a mother just then; she stopped hating her body, fell in love with her future husband, took a life-changing job, eventually wrote this book. Having an abortion was not, West writes, “intrinsically significant, but it was my first big grown-up decision—the first time I asserted, unequivocally, ‘I know the life that I want and this isn’t it’: the moment I stopped being a passenger in my own body and grabbed the rudder.”

This month, the Supreme Court is set to rule on the biggest abortion case in two decades. The case, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, challenges several Texas laws that make it harder for women to obtain abortions and harder for doctors to provide them, and shut down most of the abortion clinics in the state. The decision is expected to outline just how far states can go in restricting abortion rights—necessary guidance, given the 288 restrictions on the procedure enacted since 2010. After the death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, women’s health advocates are no longer worried that this case could be a vehicle to overturn Roe v. Wade. Still, it’s a white-knuckler: If the Texas restrictions are upheld, even just in the Fifth Circuit (Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi), more states could follow suit, and for many American women abortion could become little more than a right written on paper.

In an attempt to illustrate for the justices that abortion is a normal medical procedure tens of millions of American women have relied on—a procedure that has allowed them to stay in school, fall in love, escape abuse, raise the children they already have, parent children when they are ready—a group of female lawyers submitted their own abortion stories to the Court. Many of them are like West’s and Valenti’s, not exactly happy but not particularly painful; others are harder, about a pregnancy gone wrong or a life suddenly gone sideways. They are all stories of profound gratitude, of opportunities not foreclosed upon, of the power in voicing what women are told should bring silence and shame. Reading them, I recognized a few names: A successful former classmate, a civil rights crusader I once interviewed for a story, one of my professors from law school.

This is not the first time women have spoken out about their abortions—before Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, abortion speak-outs were a part of pro-choice advocacy, and Ms. magazine famously published a list of prominent women who had ended their pregnancies. But at a moment when it seems like everyone is a feminist and yet the fundamental right to decide whether or not to stay pregnant is again up for debate, reading these stories—the lawyers’ brief and the ones in these books—feels like peeling back old skin. Such declarations exist both because of the paths forged by feminists decades ago and because of a public increasingly open to women’s voices—a new atmosphere created partly by West, Valenti and other feminists who have long weathered sexist blows just to be able to keep talking.

Filipovic is a writer and lawyer

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com