As the bacon and sausages sizzle, we reach into our cupboard and pluck out a tin of baked beans, the very definition of comfort food for many an impoverished British student. The can is an airtight tube, sealed at both ends, and though we’ll soon chuck the empty container in the recycling bin with barely a flicker of appreciation, this simple technology was once a marvelous revolution in culinary history, and the result of a strange co-operation between enemies.

For millennia, an army had “marched on its stomach,” to quote celebrity Corsican Napoleon Bonaparte, and the logistical puzzle of feeding soldiers and sailors was a head-scratcher to flummox even a chess grand master. How did one supply tens of thousands of men, miles from friendly shores or towns, with sufficient rations to fuel their grueling demands, when the food itself spoils so quickly that it needs to be replaced every few days? If an army couldn’t rely on stripping the nearby countryside of its resources, then what was the solution? In search of an answer, in 1795 the French government embraced crowd-sourcing, and offered a prize to any boffin able to solve the quandary. In 1810, after the prize money had gone uncollected for some 15 years, a cook named Nicholas Appert claimed his 12,000 francs.

The son of an hotelier, Appert had initially trained as a chef but switched to become a confectioner, a trade in which he explored the preservation of fruit in sugary jellies. For a decade he experimented with sealing food in glass jars and then boiling them for different lengths of time, and in 1804 he impressed the French Navy, and then the army, with his invention. By 1809, an official committee was called to sample his preserved foods and found them to be deliciously maggot-free. Appert clearly deserved his prize, which was handed to him on the condition that he published his theory and didn’t patent it.

And so, in 1810, The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances for Several Years appeared in print and Appert became a media darling, flogging his luxurious preserved wares from an elegant Parisian showroom. Tellingly, despite his success, he had no scientific understanding of why his techniques worked. Germ Theory, and the discovery of bacteria, was still 50 years away, and Louis Pasteur — one of the pioneering scientists to discover it — hadn’t even been born yet. Appert, the new hero of food storage, had blundered his way to victory. What’s more, though hailed as the “Father of Canning,” he hadn’t actually invented the can. Indeed, his glass jars sometimes exploded due to the high internal pressure, were prone to fracturing if dropped, and were a bloody nightmare to open, making them less than ideal for warzones.

Instead, it was another Frenchman, Phillipe de Girard, who devised the now familiar tin can. Yet, instead of touting his invention around France, Girard pursued the healthier British market instead, though this wasn’t without complications. The two nations were in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars and Britain wasn’t exactly rolling out the red carpet to people with thick Gallic accents, so Girard hired an English merchant called Peter Durand to take out the patent on his behalf. But, clearly his invention was of sufficient interest to suppress any xenophobic Frog-bashing from the scientific community, as records show Girard somehow snuck out of France to make regular visits to the Royal Society in London.

Intriguingly, de Girard’s involvement ended soon after as his patent was snapped up and put into production by Bryan Donkin, an English engineer, who wowed the Duke of Wellington and the British Admiralty with his long-life canned meats, preserved within the tin jacket. By 1814, these novel tin cans were sailing the high seas and trundling across the battlefields of Europe, to the delight of sailors and soldiers who wrote back to London exclaiming joyfully that their dinners were no longer accessorized with weird-smelling mold. Just five years after Appert had picked up his prize check from the French government, Napoleon Bonaparte faced off against the British at the infamous Battle of Waterloo in 1815, where he may have been royally peeved to discover that not only were his adversaries carrying tinned food in their wagon trains, but that a Frenchman had been the one to put them there. So much for patriotism.

Thankfully, our own can of baked beans has one of those new-fangled rings pulls on the top, and doesn’t require the dreaded can-opener to be clumsily clamped over the metal lip. Still, at least the thing exists — in a weird quirk of history, the can-opener wasn’t invented until 1870, a lengthy 48 years after the can itself. It seems people spent the best part of half a century frustratingly smashing the tins open with hammers and chisels as if they were the furious bone-thumping apes in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

YOU SAY POTATO . . .

The guards stood defiantly around the edge of the fields, weapons in hand, as the local peasants peered past them, hunting for clues as to what precious luxury might be sprouting from the soil. Their curiosity inflamed, the locals patiently waited for dusk to settle and watched with eager delight as the soldiers abandoned their posts and traipsed to their barracks for the night. With no sentries on duty, these scruffy peasants scurried out into the fields, dug up the crops by moonlight, and ferried them quietly back to their own strips of land for replanting. Whatever aristocratic nosh this was, they were going to sample it first. When news of the dramatic theft reached the owner of the fields, he was delighted. His cunning plan had worked brilliantly.

As we chuck some shredded-potato hash browns into the frying pan, it may not occur to us that the story of the potato is a controversial one, and that the humble spud was once greeted with a mixture of haughty disdain and desperate panic. As with tomatoes, potatoes had been a South American food and the Incas had grown them at altitude, making use of the night frost to freeze-dry the tubers into dehydrated starch, almost like our frozen French fries, and this had allowed potatoes to be a long-life food source to fill the gap when other crops failed. Yet, upon arrival in Europe in the 1570s, the launch of such a nutritious and practical foodstuff was nothing but a spectacular PR disaster.

In 1596, the Swiss botanist Caspar Bauhin named the potato Solanum tuberosum esculentum, but provided a scarily dramatic drawing of the plant in his book and accompanied it with scurrilous gossip, suggesting that it caused flatulence, lust and leprosy — a holy trio of embarrassment, guaranteed to ruin any romantic encounter. We’re not sure why he decided this, but perhaps he came to this conclusion due to the somewhat lumpen, gnarly shape of his sample potato, which maybe resembled the ravaged limbs of lepers. This awful write-up gave the humble spud the kind of dreaded reputation more recently witnessed with Mad Cow Disease, and — as with the collapse of trust in British beef — soon people refused to eat potatoes, even in desperate times of famine.

The owner of those aforementioned ransacked fields was Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, a French food scientist who’d formerly been a prisoner of war and who had been fed by his Prussian captors with a lowly diet of horse food — i.e. potatoes — yet had emerged after three years of captivity in robust health. Clearly, potatoes weren’t some ungodly source of horror after all. Determined to prove his theory right, Parmentier began a long campaign to convince scientists, farmers, the French government and the superstitious population that potatoes were a useful alternative to bread, and not some fart-inducing aphrodisiac that made your legs fall off. In 1771, he managed to convince the scientists but still faced stiff opposition, so began plotting his clever series of promotional stunts, including serving potato dishes to celebrities, such as Benjamin Franklin; convincing Marie Antoinette to wear potato flowers in her posies; and fooling the peasants of Neuilly, west of Paris, that his heavily guarded potato crop — grown on 50 acres of sandy wasteland — was a new luxury food not intended for their low-born tummies. The reverse psychology, as we already know, was a triumph.

Parmentier is now celebrated with potato recipes named in his honor, and thanks to his efforts the starchy spud gradually shimmied its way up the nutritional ladder, from horse fodder, to emergency rations in a famine, to staple food source. Yet, tragically, in Ireland this former back-up option, there to plug the gap in times of crop-failure, ended up as the primary foodstuff and such over-reliance proved to be disastrous when the disease-prone tubers suffered a catastrophic blight.

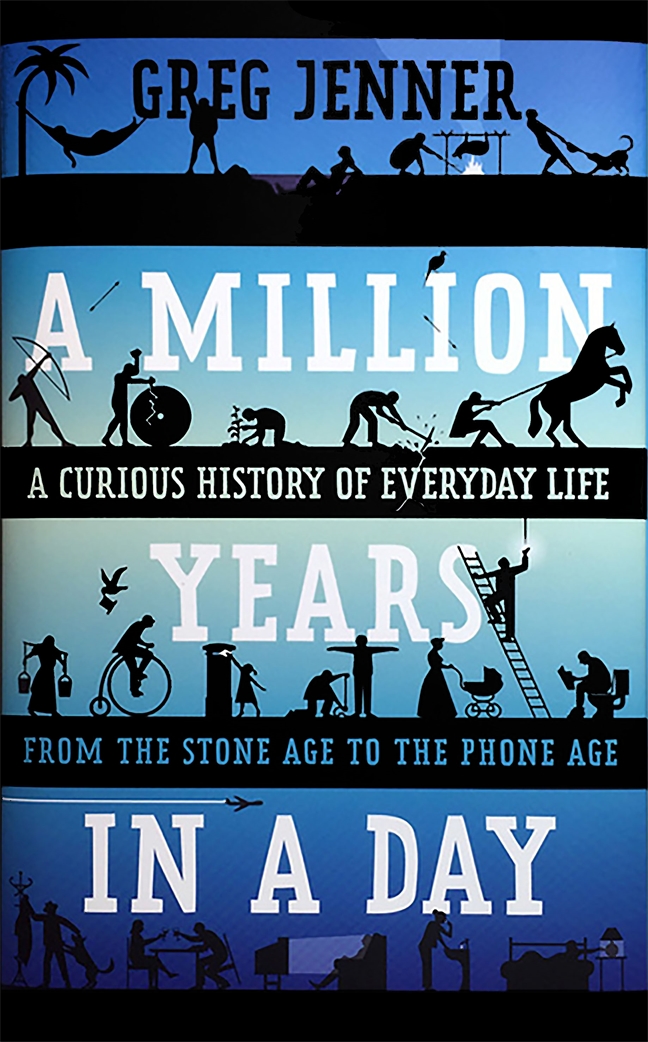

From A Million Years in Day by Greg Jenner. Copyright © 2016 by the author and reprinted by permission of Thomas Dunne Books, an imprint of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com