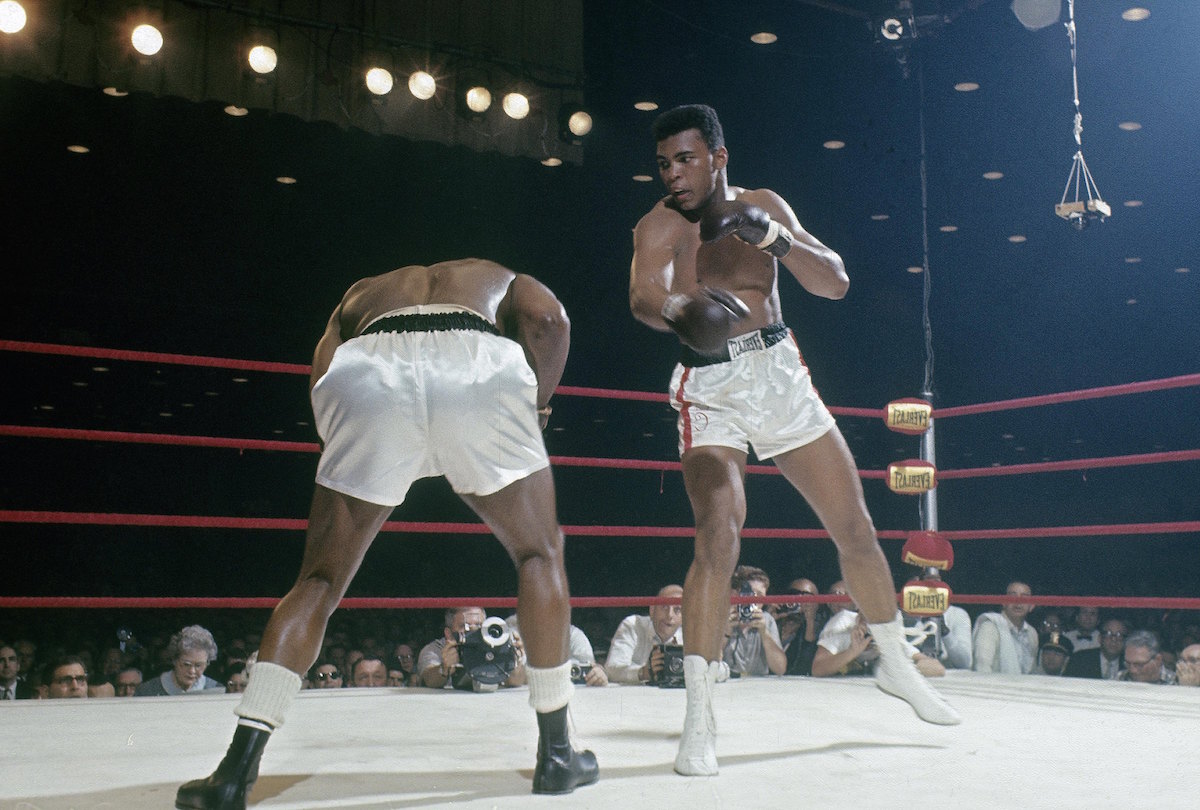

When Sonny Liston failed to return to the ring after the seventh round, ceding the heavyweight boxing championship in 1964, the media—which had largely bet against his rival—was forced to deal with, as TIME put it, the “mouth and magic” of Cassius Marcellus Clay.

Clay wasted no time rubbing his win into the faces of a naysaying media, shouting, as the magazine reported:

“Hypocrites!” yelled Cassius Clay at the press conference. “Whatcha gonna say now, huh? Huh? Who’s the greatest?” “Cassius,” came the faint reply—too faint to satisfy the new champ. “Let’s really hear it!” he hollered. “Who’s the greatest? I’ll give you one more chance: Who’s the greatest?” The chant was loud and clear. “You, Cassius, you. You’re the greatest.”

But Cassius Clay would not be the greatest for long. Weeks after that Feb. 25, 1964, win, the champ had a new religion, Islam, and a new name, Muhammad Ali. When the media rejected his new identity, Ali hit back hard as Alexandra Sims noted in a recent article for the Independent. “Cassius Clay is a slave name,” he said. “I didn’t choose it and I don’t want it. I am Muhammad Ali, a free name — it means beloved of God, and I insist people use it when people speak to me.”

The idea of rejecting a “slave name” has been a resonant one for many, but it comes with a twist in Ali’s case. Truth is, Ali’s father—Cassius Marcellus Clay, Sr.—was named after a Kentucky slave owner turned abolitionist.

The original Cassius Marcellus Clay (1810-1903), nicknamed Cash, was the son of Kentucky Revolutionary War veteran, politician and slave-owner General Green Clay. While at Yale College, Cash heard a speech by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who influenced the aspiring politician’s anti-slavery sentiments. Unlike Garrison, who called for the immediate end to slavery, Cash became an emancipationist supporting gradual emancipation.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

During the 1840s, Cash was elected to the House of Representatives and twice won reelection; but his anti-slavery views cost him his House seat and almost his life, as he survived two assassination attempts. The death threats continued when he freed his slaves and began publishing the anti-slavery newspaper The True American in Lexington, Ky. When vandals stole his publishing equipment, Cash relocated the office to Cincinnati.

In the 1850s, Cash gave abolitionist John G. Fee a ten-acre homestead on the edge of his property where Fee built Berea College, the first integrated institution of higher learning in the South; Cash was also a founding member of the Republican Party and was pivotal in the campaign to elect Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Cash served as Lincoln’s minister to Russia, where he witnessed the Tsar’s edict of emancipation, which liberated 23 million people from serfdom.

It is often the case in American history that black and white families from the same regions who share the same surname have familial ties, and in fact Clay family lore does say that the boxer was descended from a cousin of his namesake. In any case, they shared their flamboyant personalities and gifts of gab. According to biographer David Smiley in his book The Lion of White Hall, Cash was braggadocious and continuously talked about his military exploits in the Mexican-American War to anyone who would listen. No stranger to controversy, Cash ignited a firestorm on his return from Russia in 1862, on the brink of the Civil War, when he publicly rejected the president’s offer of a military command.

Cash accused Lincoln of “trying to conquer the rebellion with the sword in one hand and the shackles in the other” because he refused to liberate slaves in Confederate territories. “You allow four million of good Union men in the South,” he chided, “who are your natural allies, to cut your own throats, because you cannot lay aside a sickly prejudice.” The media had a field day as newspapers all over the country reprinted the speech.

Cash believed he had scored a major political victory on Sept. 22, 1862, when Lincoln issued a preliminary proclamation warning the Confederates of his intention to free all slaves within territories still in rebellion against the Union. The ambassador no doubt bragged that he had finally brought the president to his senses—but Cash would receive no sign of appreciation from Lincoln. According to the diary of Illinois Senator Orville Browning, Lincoln thought Cash was “conceited” and wanted “to control everything—conduct the war on his own plan and run the entire seat of government.”

After the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on Jan. 1, 1863, Cash resigned his commission and returned to Russia where he remained until 1869.

The parallels between Cassius Marcellus Clay the emancipationist and the boxing heavyweight champion of the world who once bore his name, while remarkable, also make Ali’s rejection of that name all the more appropriate. After all, self-naming is one of the pillars of self-liberation. Cassius Clay was the name of an emancipator, and Muhammad Ali was the name of a free man.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Arica L. Coleman is the author of That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia and chair of the Committee on the Status of African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and Native American (ALANA) Historians and ALANA Histories at the Organization of American Historians.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com