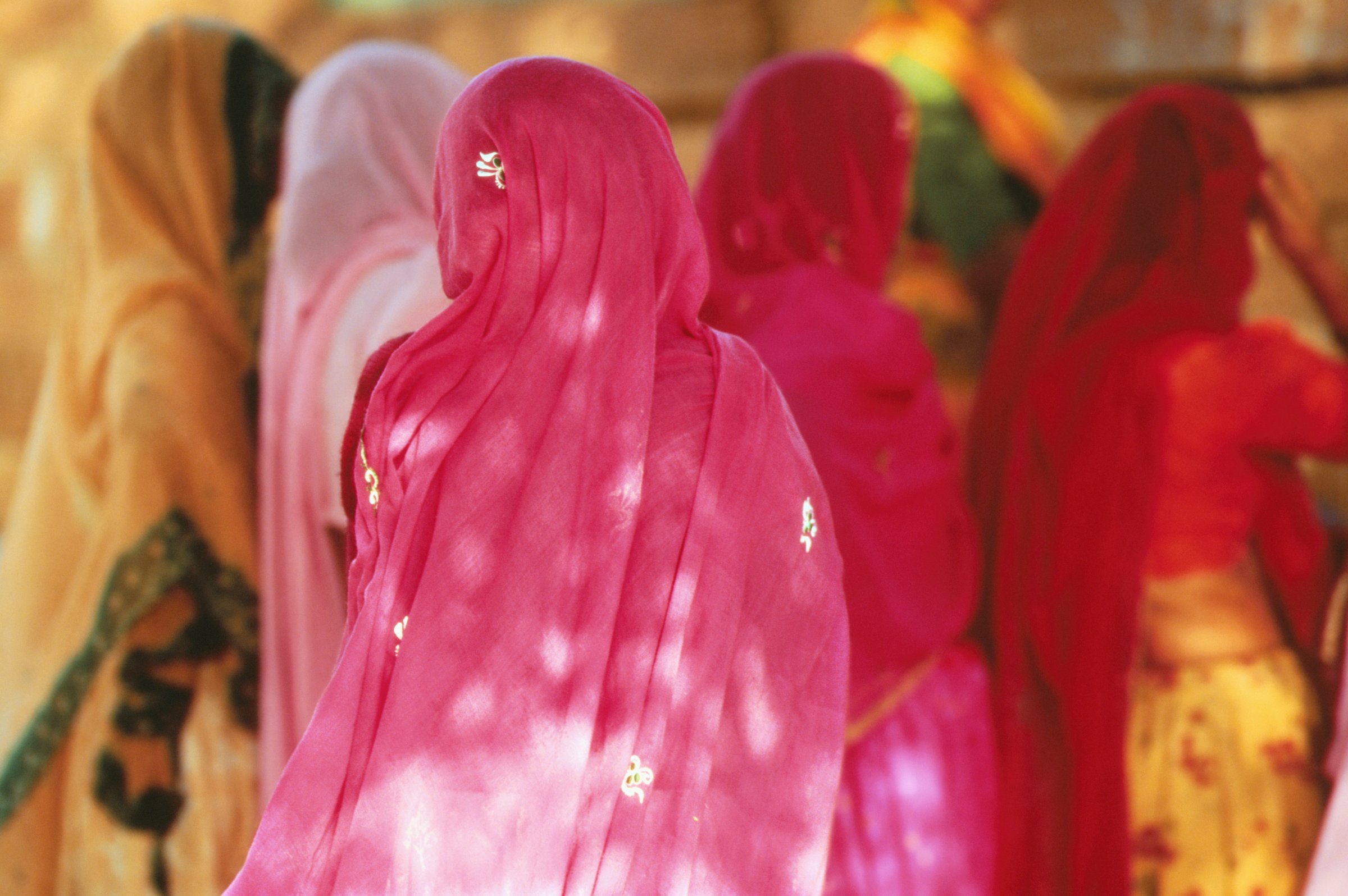

I am walking down the street, covered head-to-toe in modest clothing. I wonder if my conservative attire will protect me from the catcalls, the threats of violence, the harassment that is so common for women in my homeland of India.

The sun is hot, and I am warm in my full-sleeved shirt and tunic. My clothes are baggy; they are a size or two larger than my own. I am walking to public transportation when I realize that nothing is different. Men are still undressing me with their eyes, whizzing past while whistling in high pitched, shrill tones.

It’s not just catcalls and disgusting looks, though: A hand lingers longer than necessary when returning change; one man brushes against me when there is enough space for a car to pass.

My clothing experiment has proven to me what I’ve known all along: Harassment is not linked to a woman’s choice about what to wear, do, or say; harassment is a result of a deeply patriarchal culture that fosters degrading attitudes toward women.

Women in my country live in communities that are rife with a heady mix of sexism, patriarchy and misogyny. The National Crime Records Bureau tells us that in 2014, there were over 848 women who were either harassed, raped or killed every single day. And these are only the reported cases. Heaven knows how many more would be added to the list if all cases were brought to light.

The idea for my clothing experiment came to me when a friend from the United States visited my country. She told me she couldn’t go anywhere in India in shorts, sleeveless shirts, or knee-length skirts without being ogled at and even groped.

Her comment didn’t surprise me, but it did rekindle my anger about an issue that is near and dear to my heart: blaming and shaming the victim. And it got me thinking.

Is it a woman’s duty to “not get” violated, or raped or harassed? Is it for a woman to do everything she can so that a man can “keep his urges in check”?

If we answer these question with a “yes,” it is like saying every criminal urge is a result of external forces. In reality, it’s more often a proclivity inherent in an individual. It is disheartening to note that many believe that it is a woman’s way of dressing that causes sexual violence. Nothing in a woman’s choices or actions invites objectification.

My experiment only reiterated what I had heard from others around me: I am harassed while modestly dressed, just as I am harassed when I wear more revealing clothing. We must put the onus where it belongs: on those who perpetrate violence.

I strongly believe the root cause of any form of violence and discrimination between the genders stems from patriarchal attitudes. India is home to a deeply misogynist culture.

Some time after my clothing experiment, I decided to take my research a bit further. I made it a point to engage in conversations in public spaces and social gatherings with men, on intellectual, political, social and spiritual debates. I made it a point to read and equip myself with information that would help me carry on conversations I initiated. I held my ground, and defended my points in a clear manner. Nine times out of 10, I noticed that men in my community spent time looking at my feet or my hands when I spoke. They would not look at my face as I shared my opinions. Seven out of 10 times, I noticed that my conversation partner had completely spaced out. Three out of 10 times, I had men tell me that I was too well-read for a woman.

Some might argue it is the media that fosters an Indian society that devalues women. But this, again, is misplaced blame. Media represent women as society sees them.

In India, it is the good-natured, simple woman who keeps house that is the ideal. The woman who wears anything she wants and knows what she wants is the anomaly. The media picks up on that—so, is it fair to say that the media influences us to look at women as chattels?

Let’s take a moment and look at this objectively. A burger brand sells its products using images of a woman with a deep-necked dress holding a burger. A singer weaves in horribly sexist and violence-promoting lyrics. A car brand advertises itself with an image of a bunch of women tied up in the boot of the vehicle. Who is to blame? Is it media—or is it a society that allows these images and notions to be perpetuated?

Until we realize that patriarchy causes harm, a culture of fear will continue. I choose the word “we” purposefully because it isn’t only men who perpetuate patriarchy. It’s women, too. And all this happens because, as a community, we know no better.

Why is it that we still do not know better? We’re in a day and age when education has reached so many corners of the globe. And yet, there is a continued support circle for gender discrimination. This is especially because our education system seems to emphasize literacy, rather than sensitization and behavioral changes. Let’s expand our educational programming to allow for discussion of violence, patriarchy and respect for all.

Let’s build up educational curriculums that center on gender neutrality and sensitivity. Let’s shift the way we think about gender as rigid roles we must conform to. Together, we can create a social climate of equality that will keep violence and misogyny at bay.

We have to rise above the absolutely ridiculous considerations of inferiority or superiority of the sexes. We’re all human. Respecting differences and celebrating those differences isn’t hard, but men and women need to be taught at an early age to value all members of society.

Only then will we have a culture in India that allows for women to walk down the street without the fear or threat of violence.

Kirthi Jayakumar is a contributor from India. This piece was originally published on World Pulse. Sign up to get international stories of women leading social change delivered to your inbox every month here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com