The message was hardly subtle. A black man — wolf-whistling, paint-splattered and with a lascivious wink — approaches a pretty Chinese girl in a kitchen. She then stuffs a detergent capsule in the man’s mouth and dumps him in the washing machine. Following a quick spin, the man emerges transformed into a porcelain-skinned Chinese guy — cue the girl’s turn to be overwhelmed by lasciviousness.

The advertisement, first broadcast on Chinese television last week, prompted scorn and outrage across China, forcing Qiaobi, the firm responsible, to eventually issue not one, but two apologies. “We regret that our advertisement led to controversy,” read a statement. “We strongly oppose and condemn racial discrimination.”

Then a viral video emerged of a black American man listing things that made him “uncomfortable” about living in China. “Don’t call me heiguai [black devil],” says New Yorker Ellis Penn in Chinese, before bemoaning the irksome questions — “Aren’t they all white in America?” and “Are you big down there?” — he receives.

The video clocked up over 9 million views at time of publication, and prompted soul-searching on social media. “I have no clue how some people can say that black people look disgusting after seeing this cute guy, you know you are causing China to lose face?” posted one commenter under Penn’s video.

Speaking to TIME, Penn wants to make clear that his video was made in jest at the behest of some Chinese friends, and does not represent his experiences in China, where he’s lived for three years in the central city of Chongqing.

“I am enjoying my time in China,” he says. “Most Chinese people have never been around a foreigner or a black person and probably don’t think the questions they are asking are rude. I wouldn’t call my experiences in China negative.”

Despite 55 recognized ethnic minorities, China is a broadly homogeneous nation where 91% of the 1.3 billion population are Han Chinese. The fact is that most people — particularly in rural areas — simply haven’t come into contact with many foreigners.

“I went to a few places around China and people start to touch your skin as they don’t believe that it is real,” says Khalid Bakri, 31, a soccer coach from Sudan who has lived in Beijing for six years. “They’ve just never seen black skin before.”

Still, there are negative aspects to this unfamiliarity, exacerbated by Chinese society’s traditional aversion to dark skin — a prejudice even enshrined in classical poetry from the 6th century B.C. Today, those same international cosmetics brands that bombard Western consumers with chimerical images of coppery skin, and routinely add bronzer to moisturizer, send out the opposite message in Asia, where skin whitener is ubiquitous in beauty products. And this can reinforce already present negative stereotypes about dark skin.

Read More: China Campaigns Against ‘Western Values,’ but Does Beijing Really Think They’re That Bad?

“There are a few Chinese who are very racist,” adds Bakri. “I never have any threats but sometimes I feel uncomfortable because you want a taxi, and when he gets close and sees you’re black he doesn’t want to stop, but 10 m later he stops for someone else. Of course, they are friendly when they know you, but if they don’t know you they can not be.”

Increasingly, Chinese are becoming more familiar with black people, though, not least due to Hollywood and sports, particularly the huge following the NBA has among young Chinese. The nation, which was effectively sequestered from the outside world from World War II until 1978 — not unlike today’s North Korea — welcomed more than 130 million international visitors last year. And almost that number of Chinese traveled abroad during the same period.

Curiosity about foreign cultures has been piqued. Mariatu Kargbo, a former Miss World contestant from Sierra Leone, has lived in China since 2007 after she won a talent show singing traditional Chinese songs. “Most of the time people want me to bring Africa to their Chinese culture,” she says. “Chinese people just want to learn. They want to know all about Africa.”

Commerce has also built bridges. In the southern Chinese megacity of Guangzhou, a thriving African community has emerged — merchants who buy a hodgepodge of inexpensive local goods for export back home. Today, the commercial hub is believed to have more than 20,000 African expats. Sometimes they rub up against officialdom, most notably protests in 2012 after the death of an African man in police custody.

But the overall picture is positive. A study by Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University last month found that the overwhelming majority of more than 500 Chinese canvassed in Guangzhou did not see Africans as threatening their jobs, neighborhoods, or way of life. In fact, most saw African migrants as contributing to the local economy and the multiculturalism of the city.

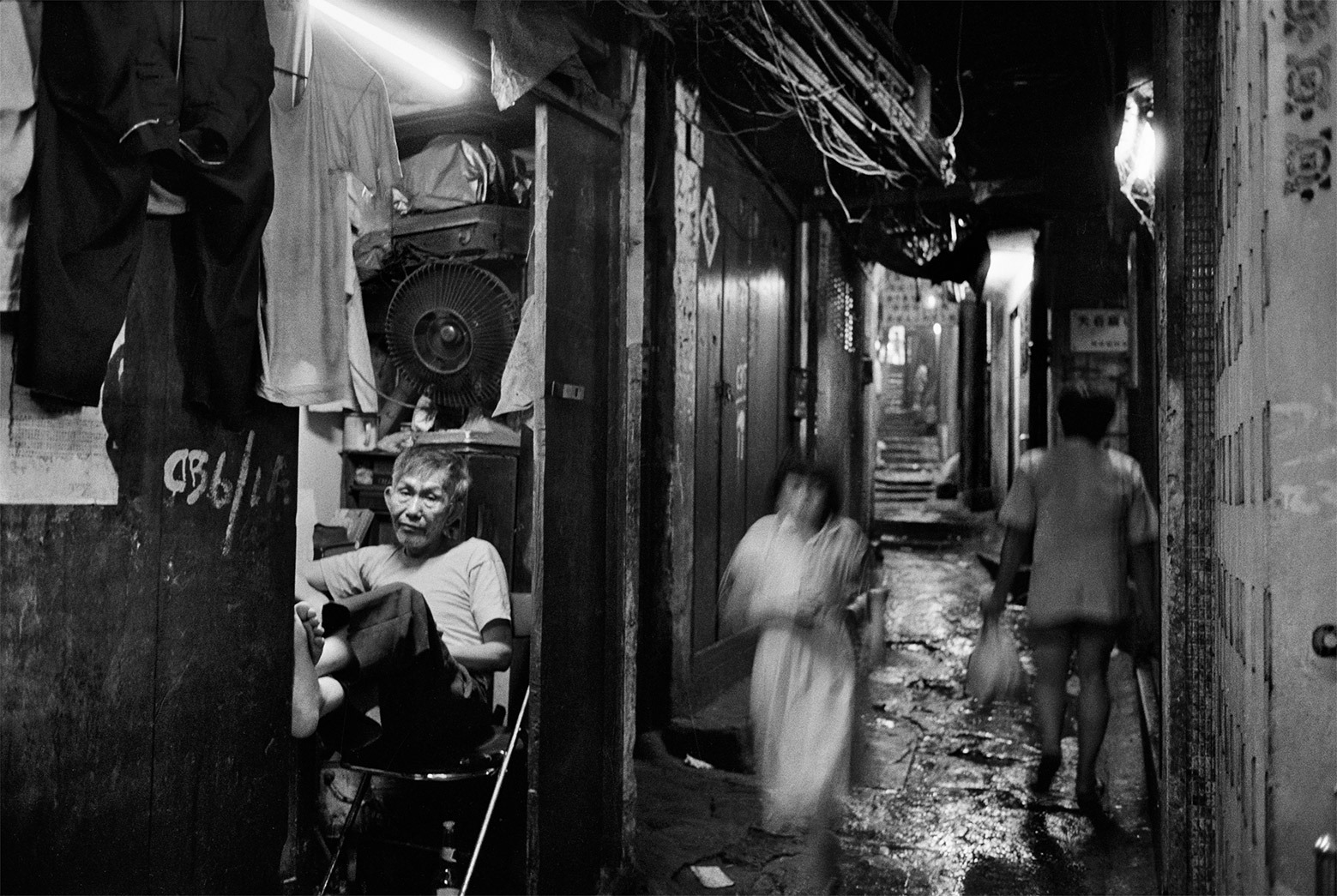

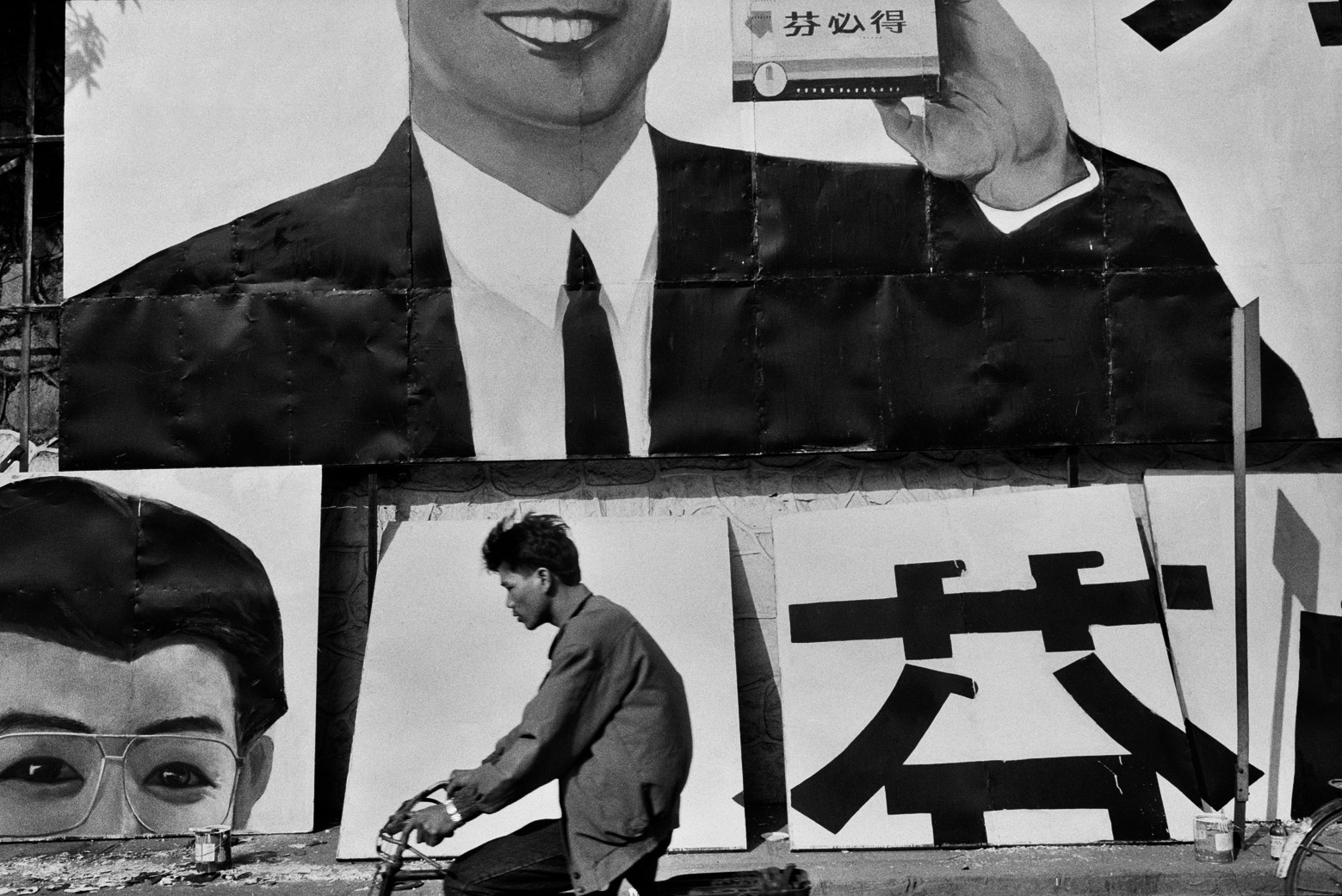

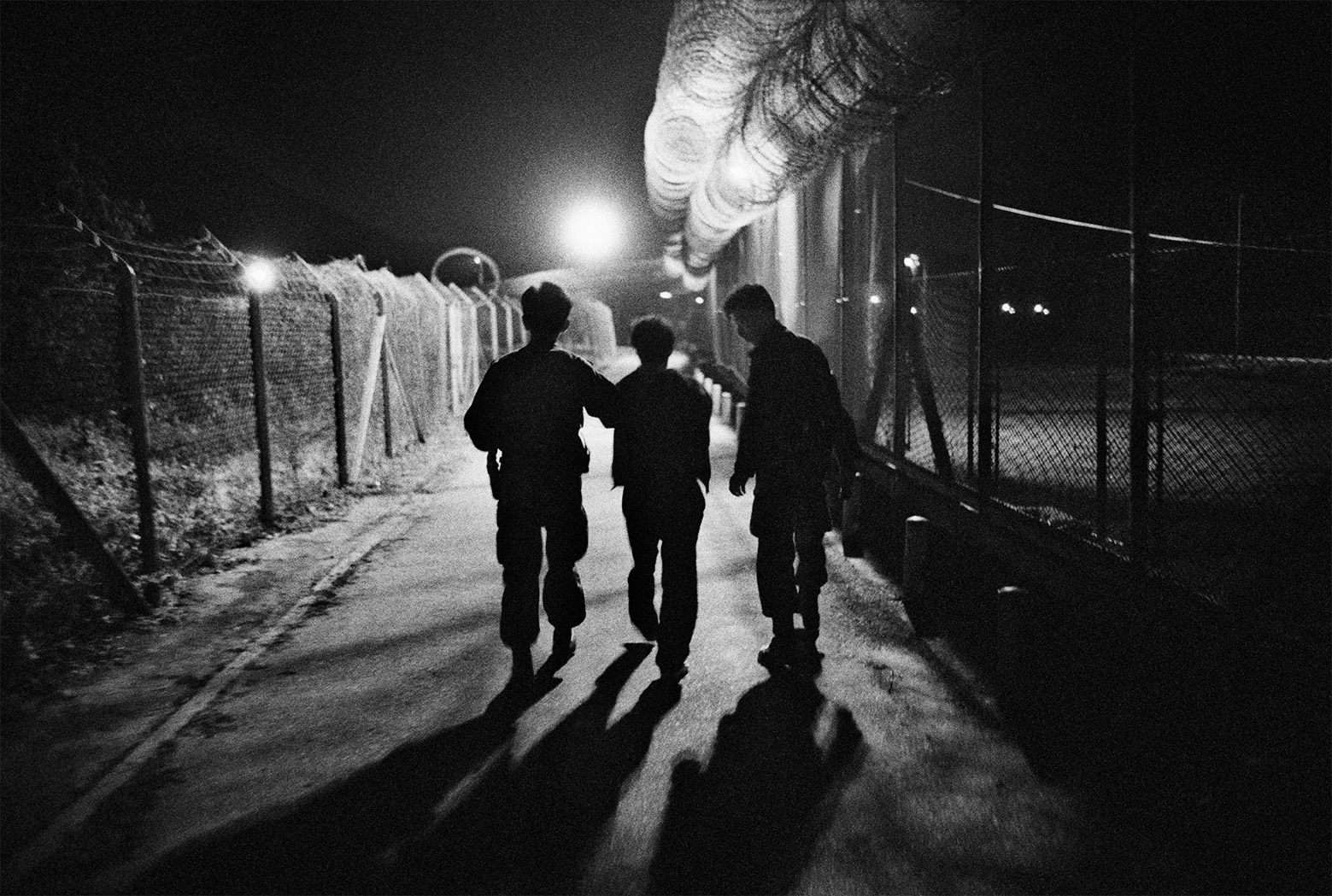

A Photographer's Farewell to China

The Chinese government has also forged impressive links in Africa over recent years — cozying to various governments, democratic and otherwise — and swapping gifts such as soccer stadiums and cash for access to the continent’s bountiful natural resources. On Tuesday, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang welcomed Togolese President Faure Gnassingbé to Beijing, pledging “cooperation in transportation infrastructure, port construction and operation, mining industry and other fields,” according to Chinese state media.

The government even commented on the detergent-ad furor. “Everyone can see that we are consistent in equality towards, and mutually respect, all countries, no matter their ethnicity or race,” said Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying. “In fact, we are good brothers with African countries.”

Today, China is Africa’s biggest trading partner, swapping around $160 billion worth of goods annually. There are more than 1 million Chinese working in Africa, mostly as laborers and traders, and not without the occasional friction and fracas that oft accompanies a large number of comparative moneyed foreigners descending on a once isolated community.

Historically, tensions have arisen in the opposite direction. During the 1970s and ’80s, when the Great Helmsman Mao Zedong was courting the support of pliant African nations in the name of “third-world solidarity,” a number of African students studied at Chinese universities. Granted better stipends than their Chinese counterparts, who felt aggrieved by their perceived wooing of Chinese women, tensions flared into sporadic violence, culminating in a riot at Nanjing University in 1988.

By contrast, many African students now study in China without encountering problems. “China is a great country,” says Ben Weles, 21, an electronics-engineering student in Beijing who arrived from his native Cameron four months ago. “Living costs in China are very expensive, but it’s O.K. I live well, there’s good accommodation. For students, it’s no problem.”

For sure, China has elements of prejudice. Many of China’s own minorities complain of marginalization and even persecution at the hands of the Beijing-based government, and xenophobic protests — particularly targeting old foe Japan — are tolerated and even inculcated by the authorities.

But ultimately, Penn says ignorance and curiosity lie behind most common misunderstandings. “I don’t think they are intending to cause an offense,” he says of the complaints in his viral video. “Every country has good or bad people, and to be honest there’s more racism in America than anywhere else in this world.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlie Campbell / Beijing at charlie.campbell@time.com