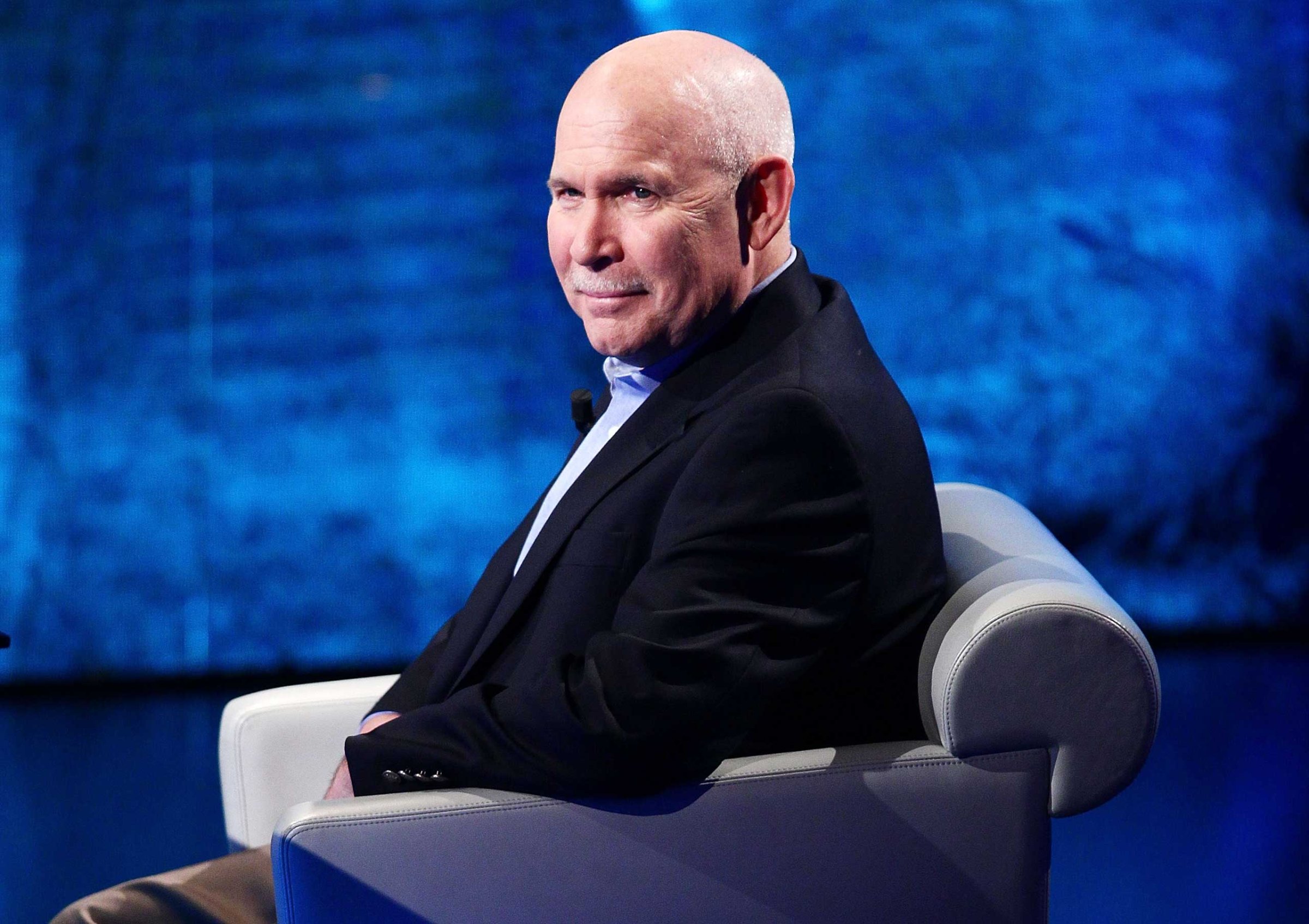

Over a career spanning more than four decades, Steve McCurry’s name has commanded respect beyond photographic circles. His books are bestsellers and his prints continue to fetch tens of thousands of dollars at auctions. So when the famed photographer was accused of photoshopping some of his images, people started paying closer attention to his work. In the last month, dozens of photographs have been exposed as manipulated. While some have been color processed – an accepted practice in photography – others show marks of cloning (where elements of an image have been removed or replaced).

McCurry’s career started in photojournalism, a field where evidence of manipulation beyond standard color correction and processing can break a photographer’s career (for example, the Associated Press fired photographer Narciso Contreras after he had digitally removed an object from one of his photographs).

Faced with mounting evidence of his own manipulations, McCurry has been forced to address his position in photography

“I’ve always let my pictures do the talking, but now I understand that people want me to describe the category into which I would put myself, and so I would say that today I am a visual storyteller,” McCurry tells TIME. “The years of covering conflict zones are in the distant past. Except for a brief time at a local newspaper in Pennsylvania, I have never been an employee of a newspaper, news magazine, or other news outlet. I have always freelanced.”

Over the years, McCurry took on assignments in the advertising world, he says, and for non-profits. “Some of my work has migrated into the fine art field and is now in private collections and museums,” he adds. “I understand that it’s virtually impossible to assign me to a specific category or classification, but that’s partly a function of working for 40 years, and having a career which has evolved as media itself has changed.”

McCurry is best known for his photograph of the Afghan Girl, which was featured on the cover of National Geographic’s June 1985 issue. The iconic portrait forever linked McCurry’s name with the yellow-border magazine. “No other image in my memory is so immediately recognizable and loved by such a large number of people across the globe,” Sarah Leen, National Geographic’s director of photography, tells TIME. “We are proud of that image and other iconic photographs that Steve created while on assignment for us.”

National Geographic does not “condone photo manipulation for editorial photography,” Leen adds, highlighting the magazine’s stringent photographic practices. “We receive all the raw files for every assignment, our photo editors look at every single frame and we do all of our own color production in house. I do not know of any other publication that has such a rigorous workflow.”

When asked about his own use of Photoshop, McCurry, however, cites National Geographic’s December 1984 issue, which featured one of his photographs. “I recall when my horizontal picture of the tailor in India’s monsoon was published on a National Geographic magazine cover, the water was extended down to fit the vertical format,” he says. “That use of Photoshop ensured that a powerful image wouldn’t be rejected because it was a horizontal orientation. Some would say that was wrong, but I thought it was appropriate because the truth and integrity of the picture were maintained.”

For Leen, this type of alterations is in the magazine’s past. “It was 32 years ago, a different era,” she says. “It would never happen now.”

For McCurry, however, the uproar has continued unabated for more than three weeks, with new examples of photoshopped images unveiled almost on a daily basis, forcing the photographer to announce that “going forward, I am committed to only using the program in a minimal way, even for my own work taken on personal trips.”

He adds: “Reflecting on the situation… even though I felt that I could do what I wanted to my own pictures in an aesthetic and compositional sense, I now understand how confusing it must be for people who think I’m still a photojournalist.”

Read next: Why Facts Aren’t Always Truths in Photography

The controversy has raised the issue of transparency within the photographic practice. While editorial photography must adhere to a set of industry-accepted rules, commercial and fine art photography don’t share the same standards. “It is essential that the lines between these genres are clear, well delineated and communicated to the audience,” says Leen. “Blurring these areas of photography creates confusion, skepticism and damage to all reputations involved. In the end honesty and transparency is essential.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com