For the past five years, Fabio Bucciarelli has been photographing the ongoing refugee crisis across North Africa, parts of the Middle East and Europe in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. As hundreds of thousands of migrants and refugees make the dangerous trip with the hope and dream of better lives, the Italian photographer’s goal has been to move beyond the statistics to focus, instead, on the feelings that drive these refugees. The work is published now in a new photobook called The Dream, released by FotoEvidence.

Fabio Bucciarelli speaks to TIME LightBox.

Olivier Laurent: The first thing you notice with The Dream is the unusual choice of packaging. It’s stored in a lifejacket bag. Why did you decide to do this?

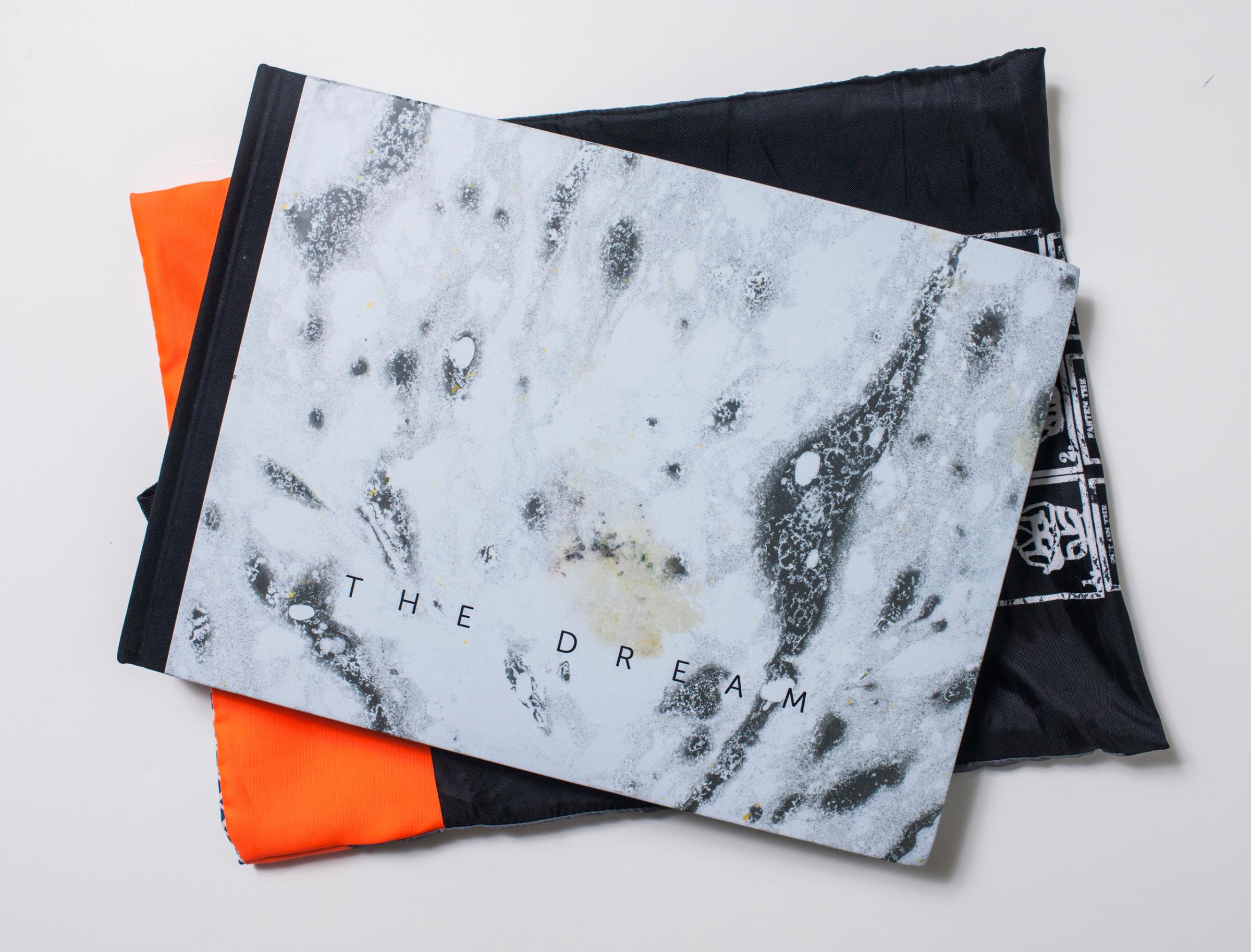

Fabio Bucciarelli: The special edition of The Dream is inserted in a “book vest” made by refugees and migrants with the life jackets they used to reach Europe. During the last year, the life jacket has become one of the symbols of this huge crisis. It’s the evidence of the great exodus, a piece of contemporary history that, over time, will become historical memory.

The concept behind this choice is the desire to offer a multi-sensorial experience focused on the humanitarian crisis, preparing the reader to a more intimate view of the book. The need to propose a real, concrete and tactile object runs in parallel with the aim to emphasize the reality of the migrant crisis and strengthen the relationship with the protagonists of the story.

Olivier Laurent: What were the logistics of getting these bags in the first place? Where do they come from?

Fabio Bucciarelli: During the first trip to Lesbos in the summer of 2015, I realized the huge number of life jackets used by refugees to reach the coast of Greece and then abandoned on the beaches. During the winter months, I became aware of the fact that the volunteers of Pika — the small reception center located on the island — were teaching refugees how to create bags and backpacks out of the life jackets. At that moment, I was looking for a “vest” for the book, a symbol that could be connected to the great exodus. So I got in touch with the camp director, Lena Altinoglou, who carried out this project with respect and determination. In March, I returned to Lesbos to work with the staff and the refugees on the prototype of the bag before they could begin commissioning. I am very proud to have them on board of this project.

Olivier Laurent: The Dream covers five years of work. When you started thinking about this book, what was your vision for it?

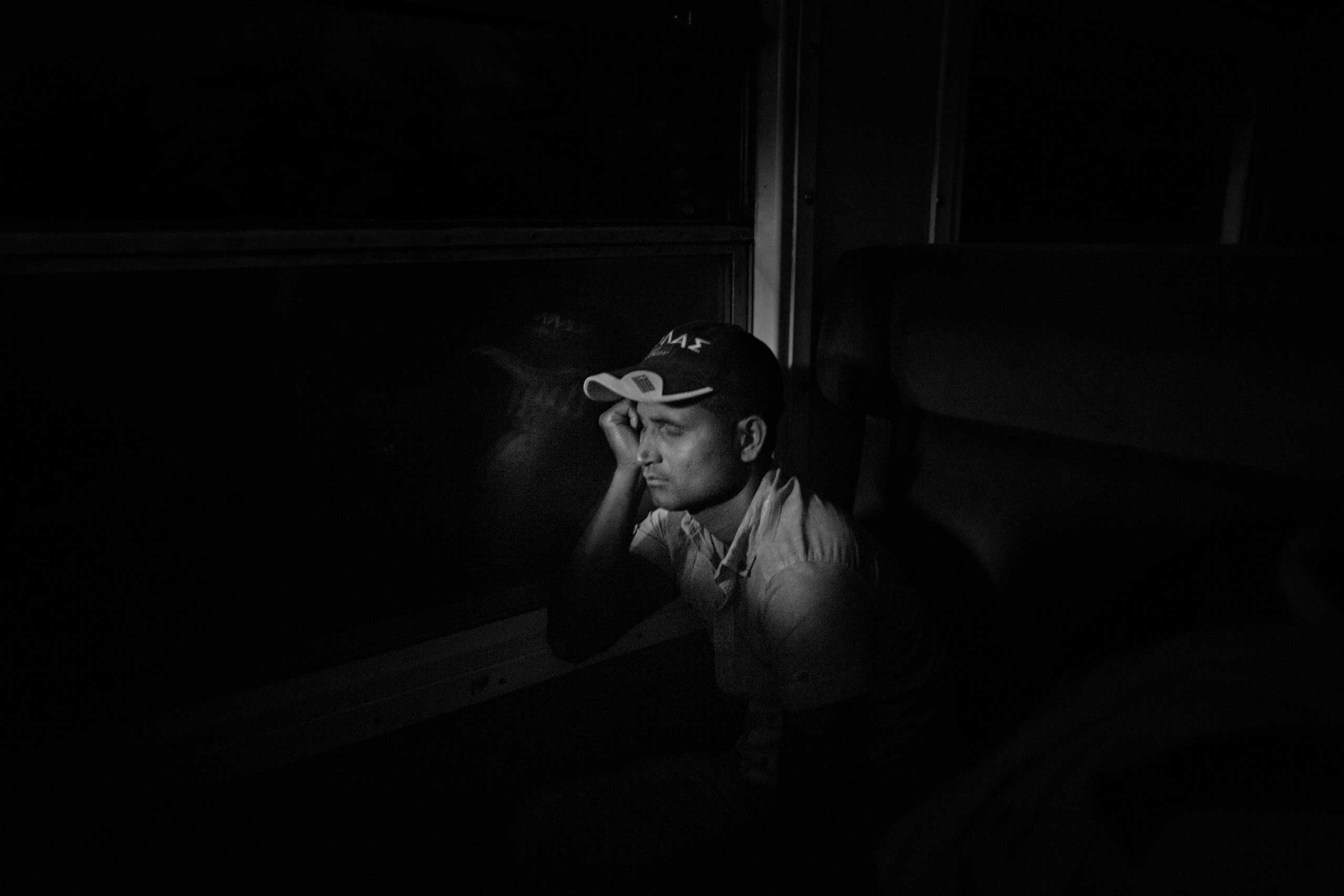

Fabio Bucciarelli: Five years ago, when the first refugees — migrant workers from Bangladesh and Sub-Saharan countries — were fleeing from the clashes in Benghazi during the Libyan civil war, I began to document their terrible suffering and inhuman condition. Even before the NATO intervention in Libya, hundreds of men and women were fleeing the fightings: a river of souls trapped in the limbo of a foreign nation.

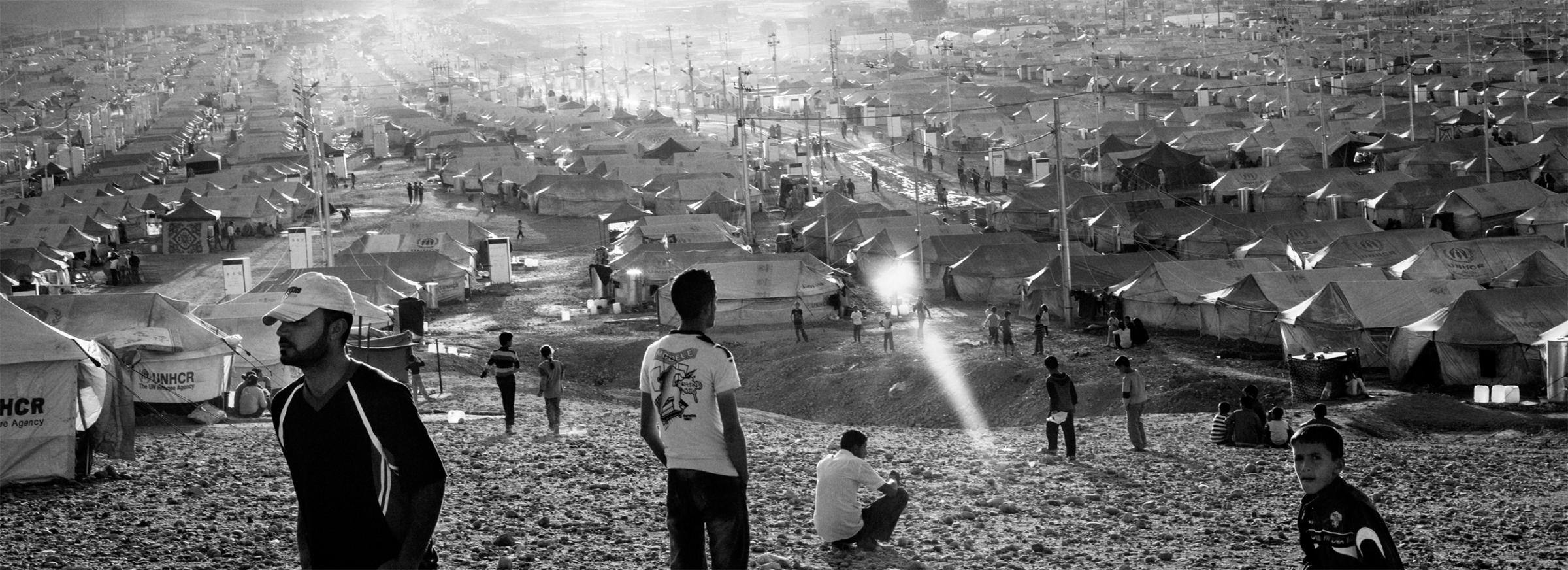

A year later, I found the same frightened glances and broken dreams along the border between Syria and Turkey: Syrian citizens fleeing from violent battles between Assad’s government and the Free Syrian Army. The beginning of a mass exodus that has now seen over seven and a half million Syrians displaced, making the current displacement of people the largest diaspora since the Second World War.

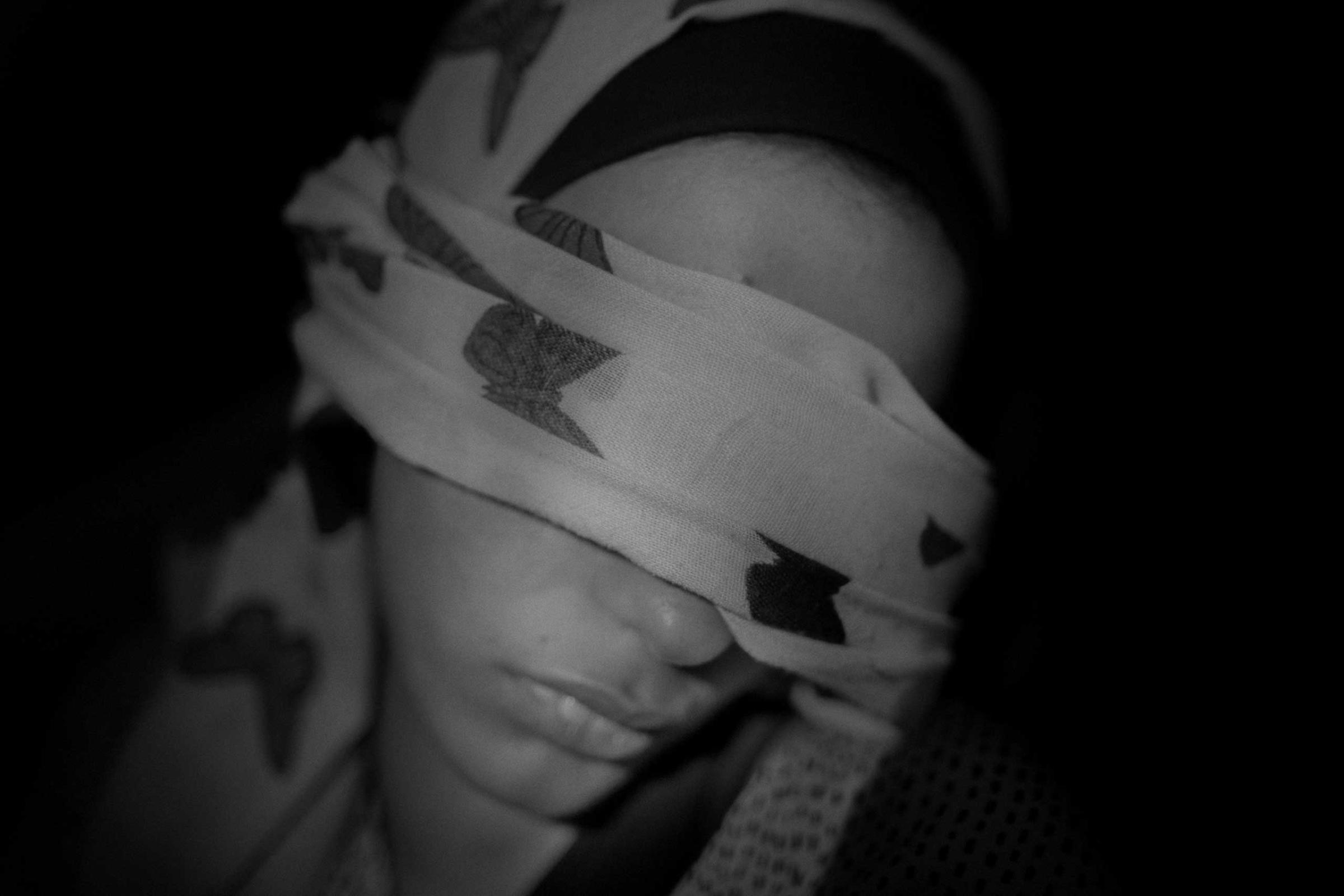

In 2015, concurrent with the growing media interest in the topic, I decided to start working on the book, pursuing the need to propose a different interpretation. I started seeing the entire work done until then from a different perspective. I was looking for humanity in tragedy, I purposely followed a language not just descriptive of the crisis, I developed a reflection focused on the dreams and the hopes of the migrants in opposition to the reality of life itself.

This was when the main idea, and the common thread of The Dream, arose and became the real engine of the trip: the dream of running away from the war, the dream of a new life, the dream of having a family, the dream of finding a job.

See Refugees and Migrants as They Sleep on Their Way to Europe

Olivier Laurent: How do you bring together such a massive amount of work in a few hundred pages? Did you work with an editor? How did you select the images?

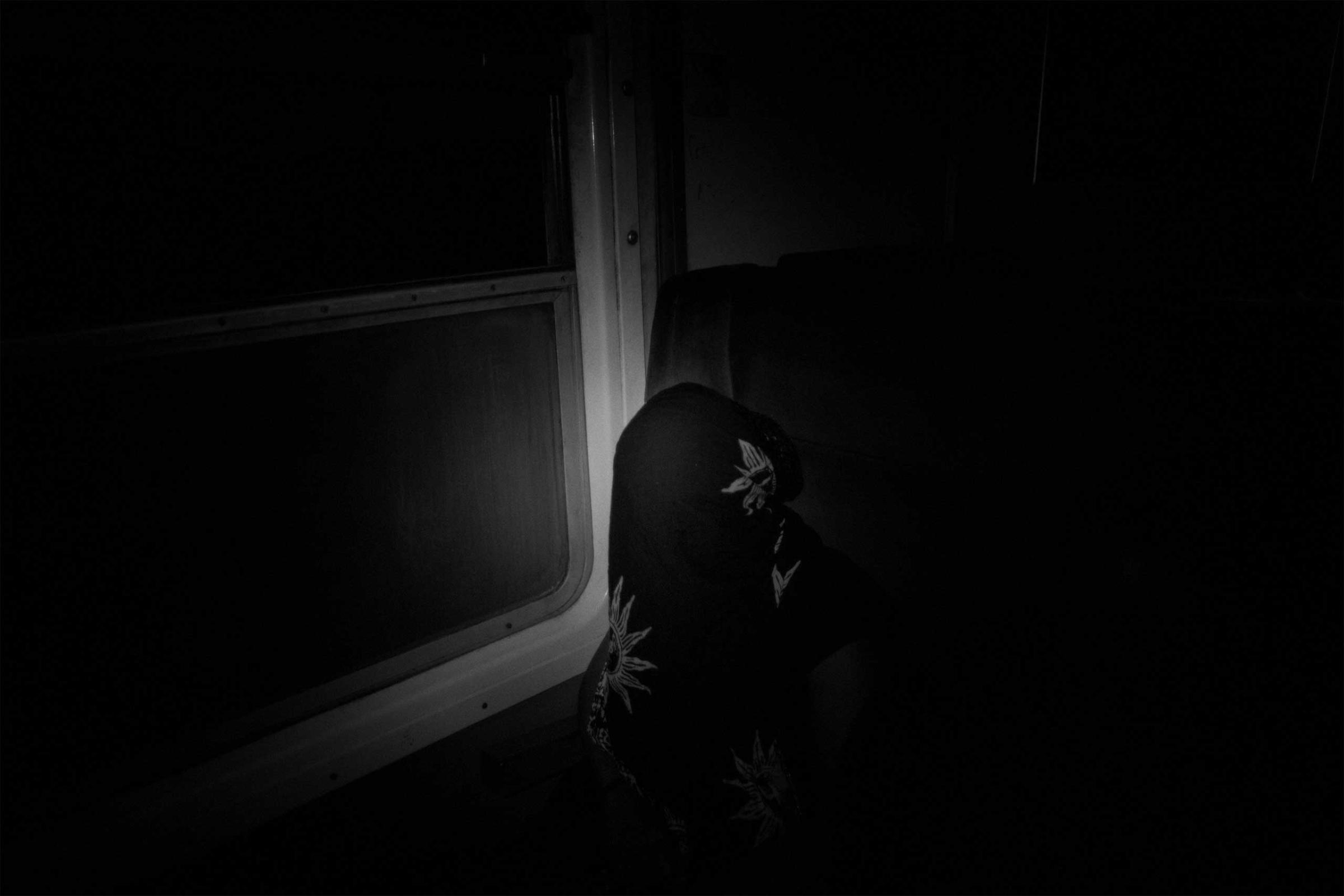

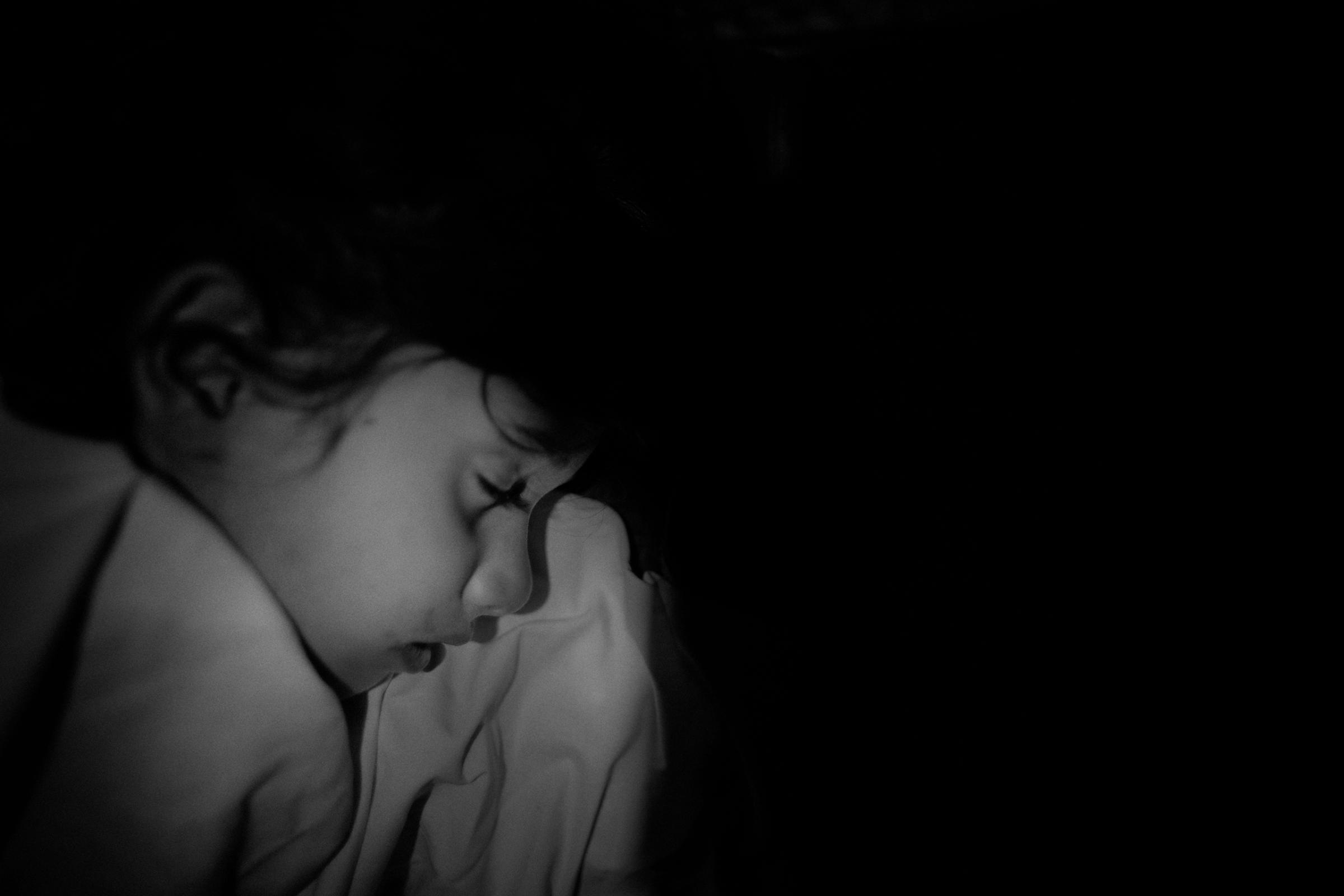

Fabio Bucciarelli: Over the years I have photographed with several cameras, including a pinhole camera: a simple camera, made of cardboard, created specifically for this project. Using my Pinolina, I made dreamlike images whose aim was not to describe reality, but to allow the viewer to connect with the protagonists, giving shape to the refugee’s emotions and offering a beat, a rhythm for the book.

In the last months of 2015, I started working on the book, looking at thousands of digital and analogue photographs I had taken over the last five years. I decided to isolate myself for two months in my house in Pineto, which became a mini newsroom. With the help of my assistant Alessandro Falco and my post producer Eduardo Matas, I worked for about two months on the book, from the creative process to the design and postproduction.

After a short time, we had selected 1,500 photographs. I printed and stuck them on the walls of different rooms to have a global view of the project and be able to work on the different ideas that could make up the book. Day after day, analyzing the different levels of meaning of the images when juxtaposed with each other, the narrative structure of The Dream took shape.

Weeks later, I met up with my friend and editor Svetlana Bachevanova of FotoEvidence (the publisher of The Dream) and the book designer to finish the book and work on the cover.

Olivier Laurent: The book uses different layout options – for example, some images are blended into each others. You also make use of blank spaces and fold-out pages. Can you explain your thinking?

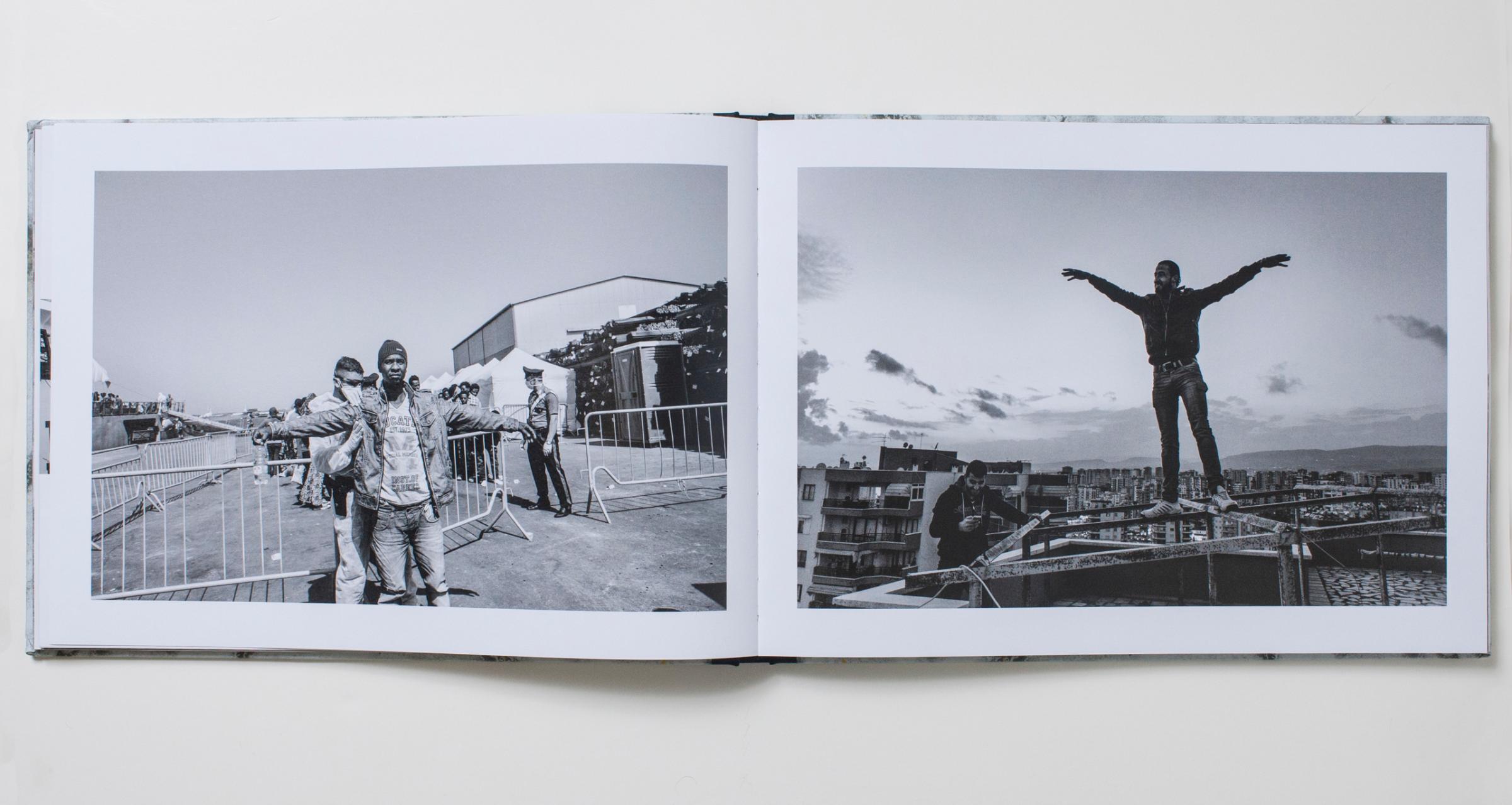

Fabio Bucciarelli: During the production of the book, I made use of various techniques to encourage the reader to investigate the migrant’s condition, including photographic sequences, color images, diptychs and collages.

The Dream wants to put a face to the numbers, reveal the full emotional spectrum of the migrants, restore their dignity and scream to the world their universal right to dream of a better future regardless of one’s origins, education or social affiliation. This means I had to remove the space-time references and captions, so that the book would not differentiate between migrants and refugees, thus forcing the viewer to focus on the human.

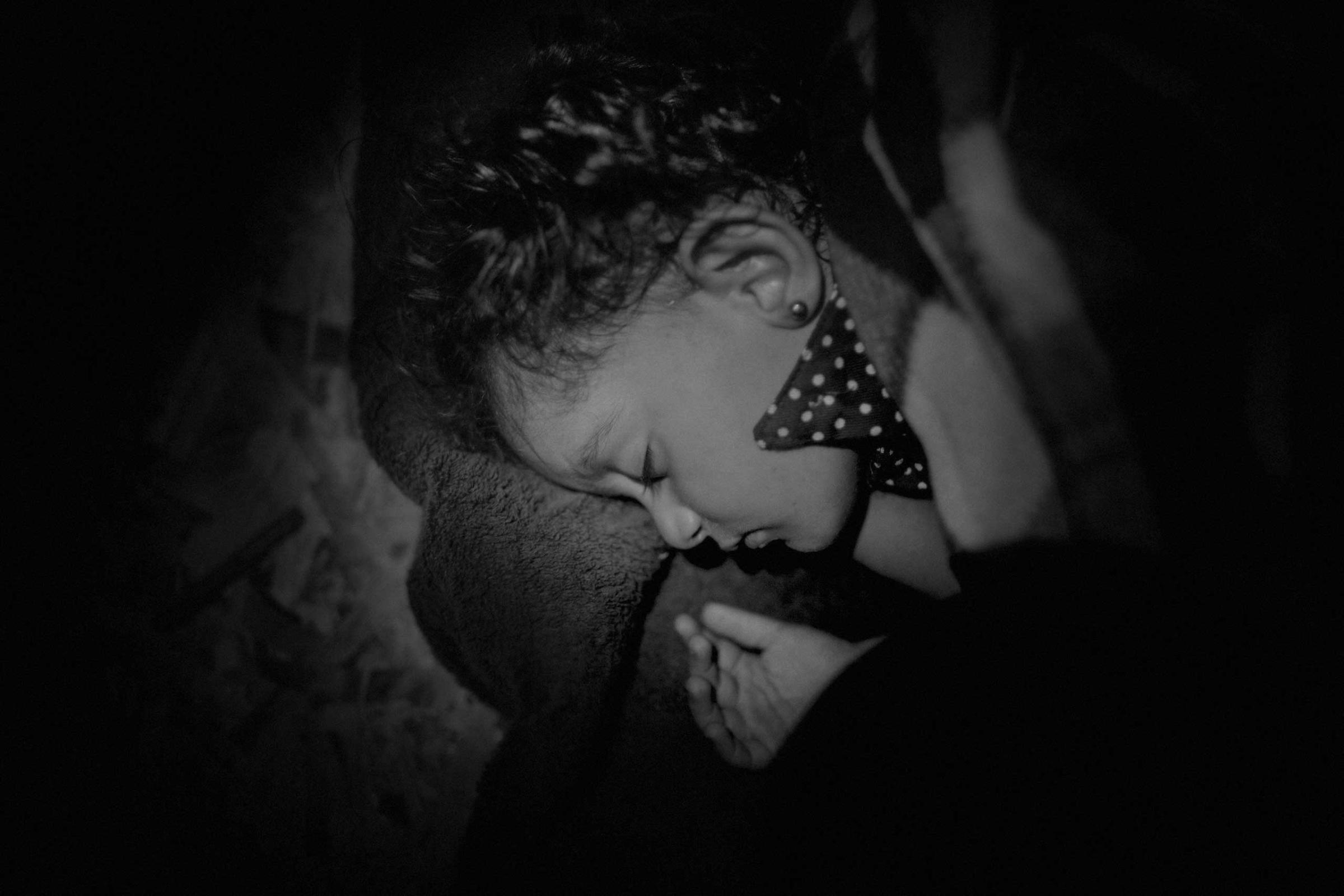

In the first part of the book, through a symbolic and dreamlike language, the reader is taken into a dream world, where memories and hopes appear to flash in the mind of migrants, resulting in an unconscious sentimental journey. Turning the pages, step by step, the book evolves and the reader is catapulted into reality; a reality that for refugees and migrants is completely different from a dream, way tougher and full of pain. The photojournalistic images start to take the upper hand leading us into a vortex of reality, from the arrivals, the camps and the funerals.

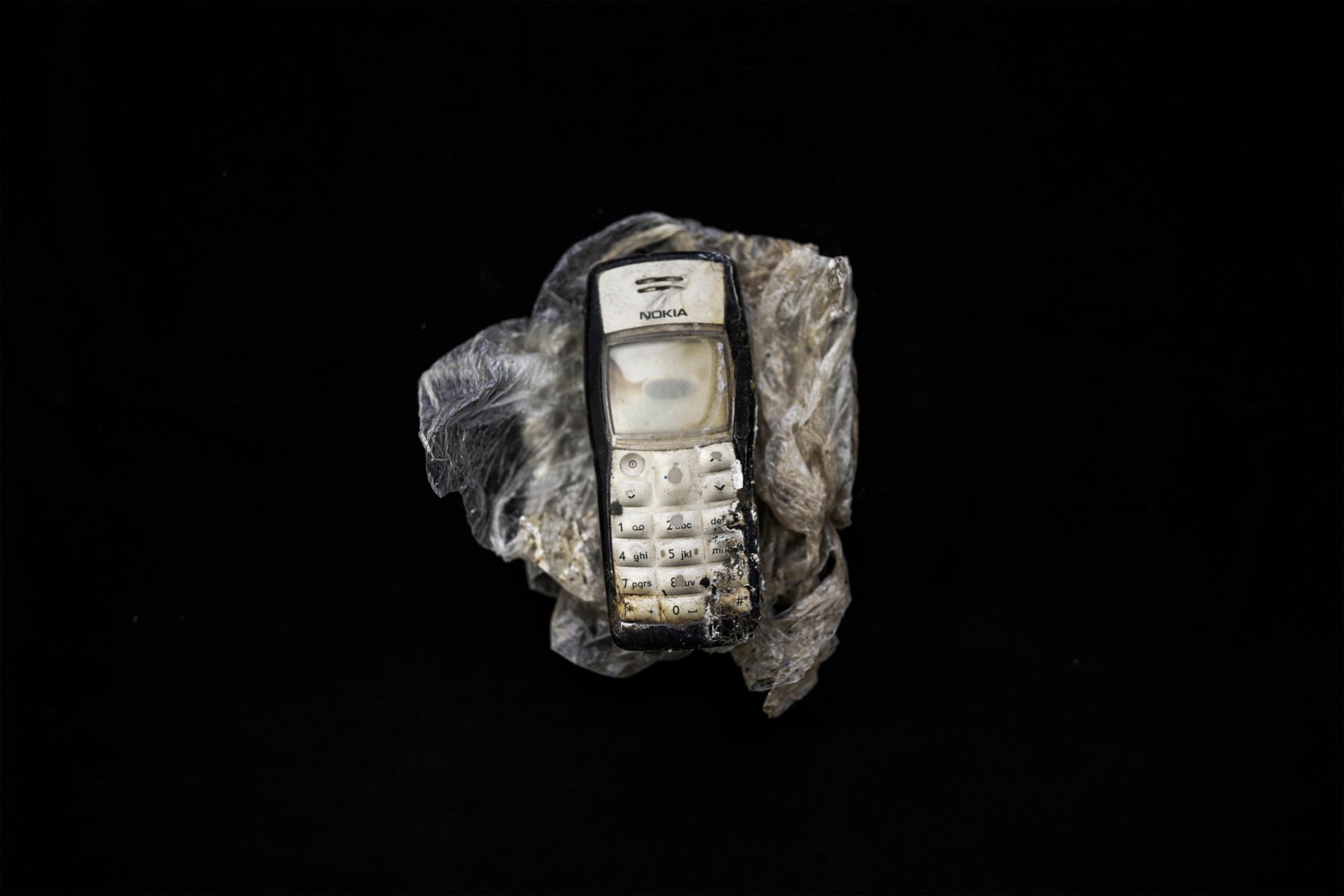

The aggravation of their condition makes the characters exhausted, so much so that they slowly return to sleep, eager to return to the dream, creating a cycle in the book that is a metaphor for their lives, caught between dreaming of a new life and their reality. The book ends with still life images of the objects that belonged to the refugees died during the route to reach Lampedusa.

For example, on these two pages, the dream of the Syrian boys who recently fled the war and who now share a moment on the roof of an hotel in Mersin, Turkey, is opposed to the reality of an African migrant who just landed at the port of Catania and raided by the Italian authorities.

Olivier Laurent: Looking back at the production of this book, is there anything you’ve learned that changed the way you look at or shoot photography?

Fabio Bucciarelli: I see photography as a communicative tool to create awareness.To document the refugee crisis, I decided to embark on a narrative experiment, between photojournalism and fine-art photography. A lucidly dreamlike photographic story for a book that comes to light at a time when the refugee crisis is a major contemporary issue, often documented by the media in an impersonal and sensationalistic way, generating indifferent, if not hostile, public opinion toward migrants.

After years spent documenting the causes and consequences of conflicts, I felt the need to use a new language to propose a humanist approach to the refugee crisis, far from the news.

Fabio Bucciarelli’s The Dream is available now. Follow him on Instagram @thedream_project.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com