This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

There is something wonderfully seductive about our gadgets. Sleek and futuristic, they seem not of this world – and certainly not of the toxic, noisy world of extractive rock mining. Few think of the ecological impact of our craving for a range of lightning-quick, portable and disposable devices. The smartphones that allow us to connect instantly with the far corners of the planet rely on as many as seventeen so-called rare earth metals such as scandium, yttrium and lanthanides.

Few have even heard of these elements, even though they are pressed close to our skin most of the day and make our brave new digital world possible. The same is true of the material that made instantaneous global communication possible in the first place. When I ask people if they have heard of gutta-percha and I meet a blank response. Even so, gutta-percha belongs in the category of genuinely world changing materials.

The sap of a fruit tree found in the Malayan archipelago, gutta-percha solidifies on contact with the air. Subject to high temperature it becomes pliable latex that, thanks to industrial process, can be molded into intricate shapes. Its properties were discovered in the West in the 1840s, and in the next decade it became the wonder-material of the age. Type “gutta-percha” into the eBay search box and you will discover its ubiquity: photograph frames, brooches, buttons, snuffboxes, inkstands, statues and so on. If you have handled a Victorian knickknack, you have undoubtedly and probably unwittingly laid your fingers the substance. Look at the advertisements in old newspapers and gutta-percha is everywhere. You could have boots and shoelaces made from gutta-percha, dress hoops, door knobs, ear trumpets, inflatable dinghies, raincoats or walking sticks (the cane used in the notorious beating of Charles Sumner on the floor of the Senate in May 1856 was made from the Malayan latex). Resistant to acids and chemicals, it had hundreds of industrial applications. The ‘gutty’ ball transformed golf.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

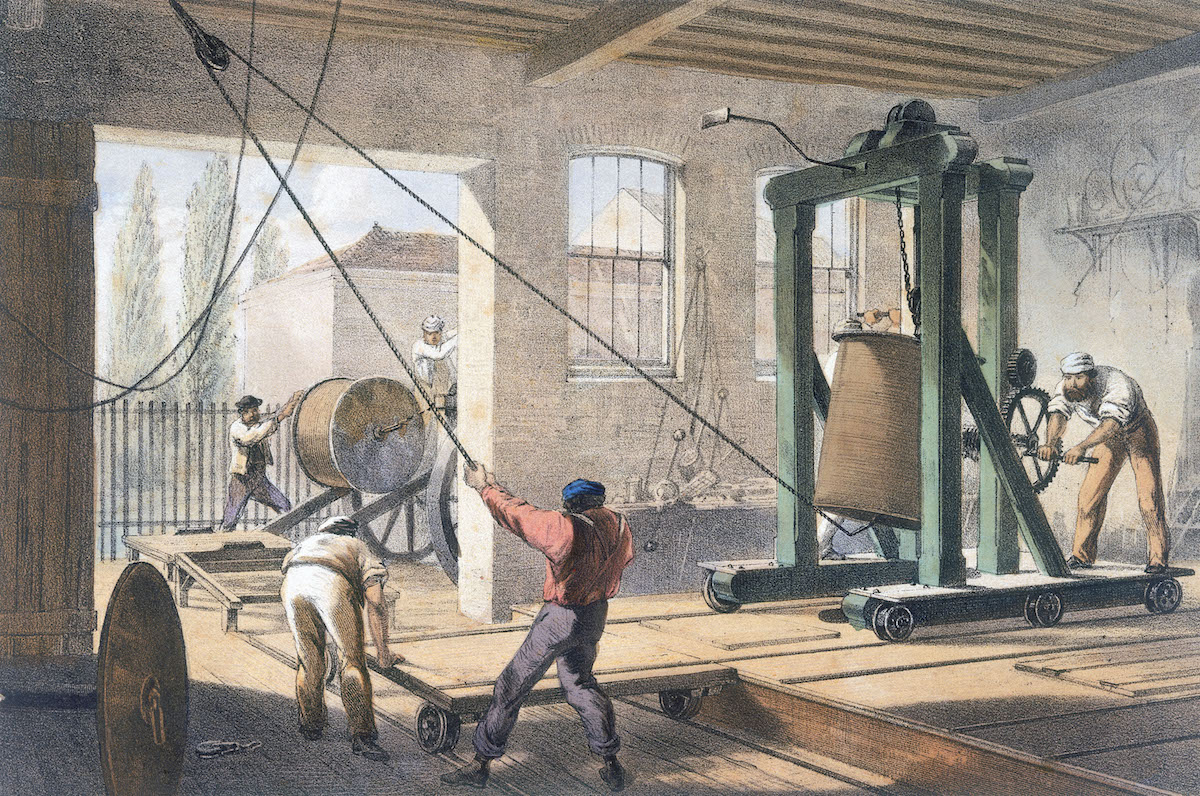

But it was not gutta-percha’s use in ear trumpets, golf balls and dress hoops that changed the world. In September 1851 a submarine telegraph was successfully laid across the English Channel, giving people in Britain instantaneous contact with hundreds of towns and cities across Europe. The engineering feat was made possible because gutta-percha proved to be the ideal insulator for copper electric wire. The Times of London said that “this conquest gained by science over the waves must ever remain recorded as amid the greatest of human achievements since record has existed of the mighty feats accomplished by man.” It was not the bridging of the narrow Channel that provoked the paper into such hyperbole; it was the realization that the entire planet could now be girdled with electric wire, reducing the gulf of months that separated distant parts of the globe to mere seconds.

Looking back at the year 1851 Thomas Hardy said that it marked “an extraordinary chronological frontier … at which there occurred what one might call a precipice in time.” Gutta-percha is a symbol of an age experiencing rapid acceleration. The 1850s saw a boom in which world trade expanded five-fold and millions of migrants ventured forth to settle what they called the wilderness. With boomtowns erupting out of the ground, clippers and steamers cutting journey times on the oceans, and railroads extending their tentacles across the world’s landmasses, this was an age of dizzying acceleration and giddy utopianism. Above all, the spreading telegraphic network seemed to herald a future of unity and peace. One journalist foresaw the “never-ceasing interchange of news” in real time across a planetary nervous system. A newspaper in 1851 marveled at the “practical annihilation of space and time” wrought by modern technologies.

Information became one of the most valuable commodities going. In the 1850s the United States exploited lucrative markets opened up by the rage for free trade. Exports of cotton, foodstuffs and lumber to Europe and Australasia surged. Increasingly intertwined with the wider world, Americans craved news. Thanks to a baton race of telegraphs and steam ships, the transmission of news between the U.S. and Europe had been slashed to a mere ten days. But, in age intoxicated by speed, that was too long. Buoyed by the success of the pioneering Channel Cable, the New York businessman Cyrus West Field set in motion the greatest engineering project of the age, a telegraph cable across the Atlantic.

Fired by almost messianic conviction, Field believed that the great endeavor would be accomplished swiftly. In fact it took years of effort, expense and repeated failure. Finally, in August 1858, the cable was successfully laid, sparking rejoicing on both sides of the Atlantic. On September 1 500,000 New Yorkers lined Broadway for the mother of all parties. The first dispatch sent down the cable brought news of an epochal trade treaty with China and of the final crushing by the British of the Indian Rebellion, vital intelligence at a time when the American economy was increasingly dependent on (as one U.S. paper put it) “such fantastical contingencies as plenty or famine, peace or war, in other quarters of the globe.” A pair of New York journalists looked forward to a world criss-crossed with electric wire and wrote that “it is impossible that old prejudices and hostilities should longer exist, while such an instrument has been created for an exchange of thought between all the nations of the earth.”

They spoke too soon. Even as New Yorkers partied, the great cable was failing. The anti-climax was crushing, but it did not stop the urge to speed up the world. Soon after the failure, the Associated Press stationed a news yacht off Cape Race, Newfoundland. Its job was to scoop canisters dropped by liners en route to New York or Boston. Inside those canisters were the latest items of world news that were telegraphed across the States from a lonely telegraph station on the edge of Newfoundland. Items with the dateline Cape Race appeared frequently in American newspapers, the place name proving that the information was piping hot. The world had to wait until 1866 when trans-Atlantic telegraphic communication at last became a reality. Within a few short years the global telegraphic network stretched from San Francisco to Yokohama and Sydney, via New York, London, Moscow and Bombay.

MORE: What the Digital Age Owes to the Inventor of Morse Code

The dream had been realized. But had it made people more peaceful and harmonious? Our own experience of digital technology suggests the answer. If anything, instantaneous communications sharpened nationalism and intensified international competition for markets and colonies. The beneficiaries were acquisitive empires and the centralizing nation state. A correspondent for the New York Times grumbled that news sent down the wire was “superficial, sudden, unsifted, too fast for the truth.”

Like the mid-nineteenth century generation, we have also trekked the path from utopianism to cynicism. Machines that once promised liberation have quickly become something darker, or at least more ambiguous. But perhaps the most important lesson is the way that the Victorians remained willfully ignorant of the materials that made their technologies possible. A single telegraph wire across the Atlantic required gutta-percha tapped from 250,000 trees. As the demand for more and more submarine cables grew, whole areas of rainforest in a neglected part of South East Asia were devastated.

The mighty trees rotted on the forest floor; none were replanted. By the beginning of the 20th century gutta-percha was about to run out. By then, however, synthetic materials were being used to insulate underwater telegraph and telephone wires and the ecological catastrophe went unremarked. (Today, gutta-percha is still used in small quantities for root canal work in dentistry.) In the digital age we are ransacking the planet for a finite supply of rare earth metals; within a few years many will be in short supply. Like the people who lived through the first age of instantaneous communication we are bad at asking what lies inside our inventions, seeing them as divorced from the natural world. Charting the story of poor, neglected gutta-percha has opened my eyes not only as a historian but as a 21st century consumer.

Ben Wilson received his MPhil in history from Cambridge University. He is the author of five critically acclaimed books, including What Price Liberty?, which won the Somerset Maugham Award. His latest book is Heyday: The 1850s and the Dawn of the Global Age (Basic Books, 2016).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Your Vote Is Safe

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- Column: Fear and Hoping in Ohio

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com