Over the past few years, the Philippines has quietly racked up economic growth that, by some estimates, is second only to China’s in Asia. The country’s outgoing President Benigno Aquino III has made needed investments in health and education. Yet this Southeast Asian archipelago nation of 100 million people still suffers from persistent poverty and crippling corruption.

Read More: These 5 Facts Explain Rodrigo Duterte’s Victory in the Philippines

Rather than gaining international attention for its economic gains, however, the Philippines now finds itself at the forefront of geopolitical gamesmanship because of rising tensions in the South China Sea, which sits to the west of the Philippines. Beijing’ recent expansion of mostly underwater reefs and rocks into islands complete with runways that can land military jets has spooked other claimants to specks of land in the vital waterway. Six governments — those of China, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Brunei and Malaysia — have overlapping claims over the South China Sea.

The smaller claimants — including the Philippines — fear China’s island-building campaign and military expansion is altering the status quo in this vital and long-contested waterway. The U.S. — by far the dominant naval power in the Pacific since the end of World War II — is similarly concerned.

Read More: Rodrigo Duterte Cancels Plans to Apologize to Pope Francis in Person

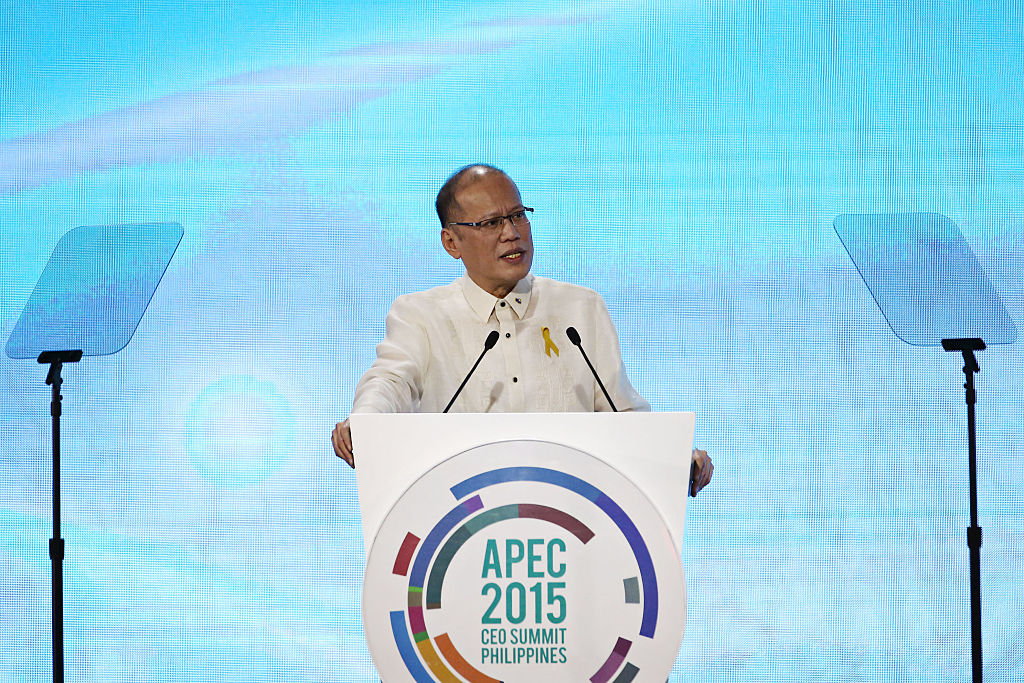

President Aquino, better known by his nickname Noynoy, has been one of the most outspoken critics of China’s construction boom in the South China Sea, which the Pentagon estimated last week has involved more than 3,200 acres of reclamation in the Spratly archipelago over the past couple years alone. During Aquino’s six-year tenure — Philippine Presidents are limited to a single term — Manila lodged a case with a U.N. tribunal questioning China’s South China Sea claims, which could be read to reserve nearly the entire waterway for itself. A decision from the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague is expected in the coming weeks. The judgment could well favor the Philippine government, but it may not matter — Beijing has already indicated that it considers the entire judicial process invalid and will not accept to the U.N. decision, which lacks any enforcement power.

After booting out a large U.S. military presence from the country in the early 1990s because of local opposition, the Philippines is now welcoming back American forces, presumably as a counterweight to China. U.S. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter last month promised joint military patrols with the Philippines. The U.S. is already bound to the Philippines by a long-standing mutual defense treaty, though Washington cautions that it does not take sides on which country should control the reefs, rocks and isles in the South China Sea.

Read More: Rodrigo Duterte: The Trump of the East?

Philippine President-elect Rodrigo Duterte, a populist gunslinger, has said that he wants to shore up relations with China that deteriorated during Aquino’s term. The 71-year-old President-elect, who will take office on June 30, says he may be willing to negotiate bilaterally with China on the South China Sea. That would be a win for Beijing, which has been pushing for bilateral negotiations with the Southeast Asian claimants, rather than a multilateral approach — likely because a unified stand by the nations China openly calls “the small countries” offer them a better chance of standing up to Asia’s greatest power.

Duterte has also indicated that a few choice roads and railways built by the Chinese on his home island of Mindanao in the southern Philippines would do much to dissipate territorial tensions. Still, Duterte’s foreign policy toward China isn’t exactly consistent. Earlier in the campaign trail, he enlivened a political debate by announcing that he would ride a jet ski to the artificial islands built by China in order to plant Philippine flags.

On May 19, a relaxed Aquino sat down with TIME at Manila’s Malacañang Palace, the same place where his mother Corazon Aquino served as President, after her opposition-leader husband Benigno Aquino Jr. was assassinated in 1983, catalyzing the People Power revolution that peacefully overthrew the regime of Ferdinand Marcos three years later. (In a country where political dynasties span generations, the kleptocratic strongman’s son Ferdinand Marcos Jr., familiarly referred to as Bongbong, ran for Vice President in the May 9 elections and looks to have narrowly lost to Leni Robredo, Aquino’s pick.) Dressed in a casual white shirt amid the ornate, wooden curlicues of Malacañang, Aquino, 56, discussed his presidential successor, tensions in the South China Sea and whether he’ll avoid the jail time that his predecessors have served. Edited excerpts of the interview follow:

What do you consider your greatest legacy?

The greatest has been a change in attitude among our people. In the period of 2010 and before that, the ultimate ambition [among Filipinos] was how to leave the country, that our country would never amount to anything, we can’t change anything. [Now there is] a preference to finding jobs here, as opposed to finding them abroad.

Was Duterte’s victory, based on an outsider campaign against the political establishment, a repudiation of your six years in office?

Well, we will study it but [his victory] was about a successful campaign. Even that 40% [of the electorate that voted for Duterte], without taking anything away from them, what portion is always interested in being on the winning side? Is it a repudiation? I don’t think so. He might be presented with facts that he was not aware of in the campaign. Undoubtedly he has begun to recognize that certain rhetoric that was allowed in the campaign might not be allowed in governance. He will adjust to the realities of governance.

How would you characterize Chinese actions in the South China Sea?

I try to put myself in others’ shoes: How does any country give up any sovereignty and expect to survive as a government? I don’t think that any Philippine President, or any leader for that matter, can afford to give up any portion of territorial sovereignty. That would be political suicide. Now you have the phenomenon of [China] creating islands that did not exist. I think at the very least [Beijing] cares about international opinion. The idea that anytime there’s a particular issue in the West Philippine Sea, [there is] a more rigid of an inspection of our bananas, that has prompted us to insulate ourselves from more interaction with [China]. And I’m sure a lot of other countries are wondering, Will this ever befall us, will this limit our ability to chart our own course? If China’s growth has been fueled by primarily by the export-driven model for such a long time, [for] continual growth, they will need positive good will from the rest of the world.

Do you think China is bullying the Philippines?

In several instances, yes. How do we match them economically? We were considered the sick man of Asia. What is heartening is that more and more of our colleagues in ASEAN [the Association of Southeast Asian Nations] see that they are trampling on the rights of one [and that] leads to the condition that everyone’s rights can be trampled on. So you have stronger and stronger statements from ASEAN, and we are gladdened by that. [Now ASEAN countries] are more engaged with China, but they felt compelled to say to China that right is right and wrong is wrong.

Has the U.S. failed the Philippines on the South China Sea issue by not speaking up initially on China’s island-building campaign and by not conducting freedom-of-navigation operations (FONOPs) near China’s artificial islands until last fall?

Well, in terms of FONOPs, better late than never. I’ve talked to so many people, so many institutions about how China works. When you talk to the [Chinese] Foreign Ministry, they tend to say a certain thing, when you speak to the central government, it seems like they’re not talking from the same page, or they are the extreme pages of the music sheet. Should we push? There is a theory that China will tend to push and if you bend, they will push some more. So we’ve had to weigh so many things. How to not exacerbate the situation. How do you give them enough room so that the idea of loss of face does not happen? It’s a work in progress.

The U.S. once colonized the Philippines. China is now the region’s preeminent economic power. Which is the lesser of two evils for a country caught between two great powers in the Pacific?

At least there are certain fundamentals [between the U.S. and the Philippines]. Strategic partnership is based on a shared set of values. We are supposed to talk as allies, as opposed to just following orders. Not to single out China, but in their system it is the [communist] party that is first and foremost. Our armed services are there to protect our people. In China it’s defined as to protect the party.

Your two presidential predecessors have spent time behind bars. Are you confident that you will not suffer the same fate?

I’m confident that nobody will find a charge that has substance. But in terms of harassment, I guess there will be. We’ve disturbed a lot of rice bowls.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com