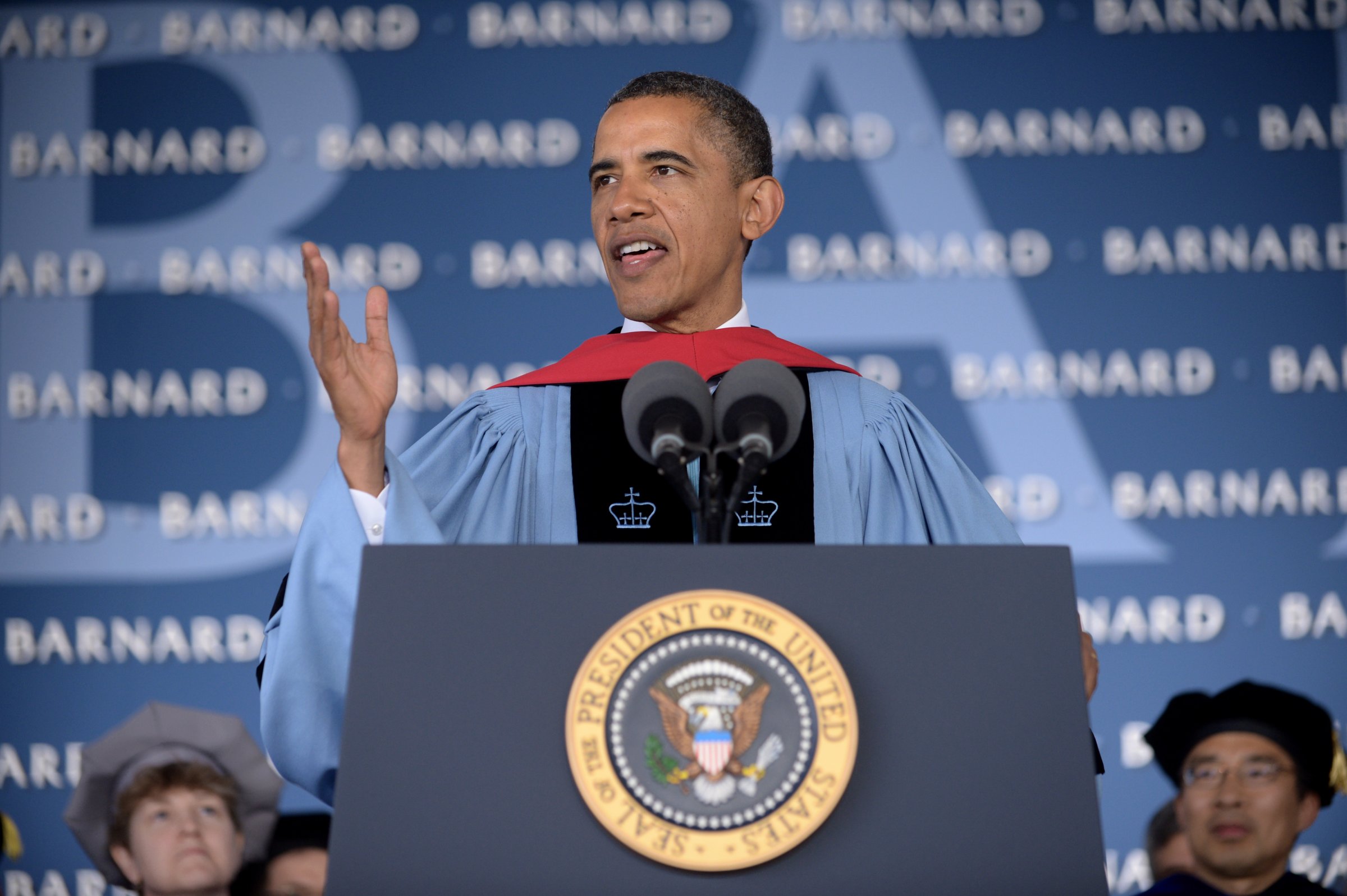

Here are the full remarks from Obama’s speech at Barnard College in New York, New York in 2012.

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you so much. (Applause.) Thank you. Please, please have a seat. Thank you. (Applause.)

Thank you, President Spar, trustees, President Bollinger. Hello, Class of 2012! (Applause.) Congratulations on reaching this day. Thank you for the honor of being able to be a part of it.

There are so many people who are proud of you — your parents, family, faculty, friends — all who share in this achievement. So please give them a big round of applause. (Applause.) To all the moms who are here today, you could not ask for a better Mother’s Day gift than to see all of these folks graduate. (Applause.)

I have to say, though, whenever I come to these things, I start thinking about Malia and Sasha graduating, and I start tearing up and — (laughter) — it’s terrible. I don’t know how you guys are holding it together. (Laughter.)

I will begin by telling a hard truth: I’m a Columbia college graduate. (Laughter and applause.) I know there can be a little bit of a sibling rivalry here. (Laughter.) But I’m honored nevertheless to be your commencement speaker today — although I’ve got to say, you set a pretty high bar given the past three years. (Applause.) Hillary Clinton — (applause) — Meryl Streep — (applause) — Sheryl Sandberg — these are not easy acts to follow. (Applause.)

But I will point out Hillary is doing an extraordinary job as one of the finest Secretaries of State America has ever had. (Applause.) We gave Meryl the Presidential Medal of Arts and Humanities. (Applause.) Sheryl is not just a good friend; she’s also one of our economic advisers. So it’s like the old saying goes — keep your friends close, and your Barnard commencement speakers even closer. (Applause.) There’s wisdom in that. (Laughter.)

Now, the year I graduated — this area looks familiar — (laughter) — the year I graduated was 1983, the first year women were admitted to Columbia. (Applause.) Sally Ride was the first American woman in space. Music was all about Michael and the Moonwalk. (Laughter.)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Do it! (Laughter.)

THE PRESIDENT: No Moonwalking. (Laughter.) No Moonwalking today. (Laughter.)

We had the Walkman, not iPods. Some of the streets around here were not quite so inviting. (Laughter.) Times Square was not a family destination. (Laughter.) So I know this is all ancient history. Nothing worse than commencement speakers droning on about bygone days. (Laughter.) But for all the differences, the Class of 1983 actually had a lot in common with all of you. For we, too, were heading out into a world at a moment when our country was still recovering from a particularly severe economic recession. It was a time of change. It was a time of uncertainty. It was a time of passionate political debates.

You can relate to this because just as you were starting out finding your way around this campus, an economic crisis struck that would claim more than 5 million jobs before the end of your freshman year. Since then, some of you have probably seen parents put off retirement, friends struggle to find work. And you may be looking toward the future with that same sense of concern that my generation did when we were sitting where you are now.

Of course, as young women, you’re also going to grapple with some unique challenges, like whether you’ll be able to earn equal pay for equal work; whether you’ll be able to balance the demands of your job and your family; whether you’ll be able to fully control decisions about your own health.

And while opportunities for women have grown exponentially over the last 30 years, as young people, in many ways you have it even tougher than we did. This recession has been more brutal, the job losses steeper. Politics seems nastier. Congress more gridlocked than ever. Some folks in the financial world have not exactly been model corporate citizens. (Laughter.)

No wonder that faith in our institutions has never been lower, particularly when good news doesn’t get the same kind of ratings as bad news anymore. Every day you receive a steady stream of sensationalism and scandal and stories with a message that suggest change isn’t possible; that you can’t make a difference; that you won’t be able to close that gap between life as it is and life as you want it to be.

My job today is to tell you don’t believe it. Because as tough as things have been, I am convinced you are tougher. I’ve seen your passion and I’ve seen your service. I’ve seen you engage and I’ve seen you turn out in record numbers. I’ve heard your voices amplified by creativity and a digital fluency that those of us in older generations can barely comprehend. I’ve seen a generation eager, impatient even, to step into the rushing waters of history and change its course.

And that defiant, can-do spirit is what runs through the veins of American history. It’s the lifeblood of all our progress. And it is that spirit which we need your generation to embrace and rekindle right now.

See, the question is not whether things will get better — they always do. The question is not whether we’ve got the solutions to our challenges — we’ve had them within our grasp for quite some time. We know, for example, that this country would be better off if more Americans were able to get the kind of education that you’ve received here at Barnard — (applause) — if more people could get the specific skills and training that employers are looking for today.

We know that we’d all be better off if we invest in science and technology that sparks new businesses and medical breakthroughs; if we developed more clean energy so we could use less foreign oil and reduce the carbon pollution that’s threatening our planet. (Applause.)

We know that we’re better off when there are rules that stop big banks from making bad bets with other people’s money and — (applause) — when insurance companies aren’t allowed to drop your coverage when you need it most or charge women differently from men. (Applause.) Indeed, we know we are better off when women are treated fairly and equally in every aspect of American life — whether it’s the salary you earn or the health decisions you make. (Applause.)

We know these things to be true. We know that our challenges are eminently solvable. The question is whether together, we can muster the will — in our own lives, in our common institutions, in our politics — to bring about the changes we need. And I’m convinced your generation possesses that will. And I believe that the women of this generation — that all of you will help lead the way. (Applause.)

Now, I recognize that’s a cheap applause line when you’re giving a commencement at Barnard. (Laughter.) It’s the easy thing to say. But it’s true. It is — in part, it is simple math. Today, women are not just half this country; you’re half its workforce. (Applause.) More and more women are out-earning their husbands. You’re more than half of our college graduates, and master’s graduates, and PhDs. (Applause.) So you’ve got us outnumbered. (Laughter.)

After decades of slow, steady, extraordinary progress, you are now poised to make this the century where women shape not only their own destiny but the destiny of this nation and of this world.

But how far your leadership takes this country, how far it takes this world — well, that will be up to you. You’ve got to want it. It will not be handed to you. And as someone who wants that future — that better future — for you, and for Malia and Sasha, as somebody who’s had the good fortune of being the husband and the father and the son of some strong, remarkable women, allow me to offer just a few pieces of advice. That’s obligatory. (Laughter.) Bear with me.

My first piece of advice is this: Don’t just get involved. Fight for your seat at the table. Better yet, fight for a seat at the head of the table. (Applause.)

It’s been said that the most important role in our democracy is the role of citizen. And indeed, it was 225 years ago today that the Constitutional Convention opened in Philadelphia, and our founders, citizens all, began crafting an extraordinary document. Yes, it had its flaws — flaws that this nation has strived to protect (perfect) over time. Questions of race and gender were unresolved. No woman’s signature graced the original document — although we can assume that there were founding mothers whispering smarter things in the ears of the founding fathers. (Applause.) I mean, that’s almost certain.

What made this document special was that it provided the space — the possibility — for those who had been left out of our charter to fight their way in. It provided people the language to appeal to principles and ideals that broadened democracy’s reach. It allowed for protest, and movements, and the dissemination of new ideas that would repeatedly, decade after decade, change the world — a constant forward movement that continues to this day.

Our founders understood that America does not stand still; we are dynamic, not static. We look forward, not back. And now that new doors have been opened for you, you’ve got an obligation to seize those opportunities.

You need to do this not just for yourself but for those who don’t yet enjoy the choices that you’ve had, the choices you will have. And one reason many workplaces still have outdated policies is because women only account for 3 percent of the CEOs at Fortune 500 companies. One reason we’re actually refighting long-settled battles over women’s rights is because women occupy fewer than one in five seats in Congress.

Now, I’m not saying that the only way to achieve success is by climbing to the top of the corporate ladder or running for office — although, let’s face it, Congress would get a lot more done if you did. (Laughter and applause.) That I think we’re sure about. But if you decide not to sit yourself at the table, at the very least you’ve got to make sure you have a say in who does. It matters.

Before women like Barbara Mikulski and Olympia Snowe and others got to Congress, just to take one example, much of federally-funded research on diseases focused solely on their effects on men. It wasn’t until women like Patsy Mink and Edith Green got to Congress and passed Title IX, 40 years ago this year, that we declared women, too, should be allowed to compete and win on America’s playing fields. (Applause.) Until a woman named Lilly Ledbetter showed up at her office and had the courage to step up and say, you know what, this isn’t right, women weren’t being treated fairly — we lacked some of the tools we needed to uphold the basic principle of equal pay for equal work.

So don’t accept somebody else’s construction of the way things ought to be. It’s up to you to right wrongs. It’s up to you to point out injustice. It’s up to you to hold the system accountable and sometimes upend it entirely. It’s up to you to stand up and to be heard, to write and to lobby, to march, to organize, to vote. Don’t be content to just sit back and watch.

Those who oppose change, those who benefit from an unjust status quo, have always bet on the public’s cynicism or the public’s complacency. Throughout American history, though, they have lost that bet, and I believe they will this time as well. (Applause.) But ultimately, Class of 2012, that will depend on you. Don’t wait for the person next to you to be the first to speak up for what’s right. Because maybe, just maybe, they’re waiting on you.

Which brings me to my second piece of advice: Never underestimate the power of your example. The very fact that you are graduating, let alone that more women now graduate from college than men, is only possible because earlier generations of women — your mothers, your grandmothers, your aunts — shattered the myth that you couldn’t or shouldn’t be where you are. (Applause.)

I think of a friend of mine who’s the daughter of immigrants. When she was in high school, her guidance counselor told her, you know what, you’re just not college material. You should think about becoming a secretary. Well, she was stubborn, so she went to college anyway. She got her master’s. She ran for local office, won. She ran for state office, she won. She ran for Congress, she won. And lo and behold, Hilda Solis did end up becoming a secretary — (laughter) — she is America’s Secretary of Labor. (Applause.)

So think about what that means to a young Latina girl when she sees a Cabinet secretary that looks like her. (Applause.) Think about what it means to a young girl in Iowa when she sees a presidential candidate who looks like her. Think about what it means to a young girl walking in Harlem right down the street when she sees a U.N. ambassador who looks like her. Do not underestimate the power of your example.

This diploma opens up new possibilities, so reach back, convince a young girl to earn one, too. If you earned your degree in areas where we need more women — like computer science or engineering — (applause) — reach back and persuade another student to study it, too. If you’re going into fields where we need more women, like construction or computer engineering — reach back, hire someone new. Be a mentor. Be a role model.

Until a girl can imagine herself, can picture herself as a computer programmer, or a combatant commander, she won’t become one. Until there are women who tell her, ignore our pop culture obsession over beauty and fashion — (applause) — and focus instead on studying and inventing and competing and leading, she’ll think those are the only things that girls are supposed to care about. Now, Michelle will say, nothing wrong with caring about it a little bit. (Laughter.) You can be stylish and powerful, too. (Applause.) That’s Michelle’s advice. (Applause.)

And never forget that the most important example a young girl will ever follow is that of a parent. Malia and Sasha are going to be outstanding women because Michelle and Marian Robinson are outstanding women. So understand your power, and use it wisely.

My last piece of advice — this is simple, but perhaps most important: Persevere. Persevere. Nothing worthwhile is easy. No one of achievement has avoided failure — sometimes catastrophic failures. But they keep at it. They learn from mistakes. They don’t quit.

You know, when I first arrived on this campus, it was with little money, fewer options. But it was here that I tried to find my place in this world. I knew I wanted to make a difference, but it was vague how in fact I’d go about it. (Laughter.) But I wanted to do my part to do my part to shape a better world.

So even as I worked after graduation in a few unfulfilling jobs here in New York — I will not list them all — (laughter) — even as I went from motley apartment to motley apartment, I reached out. I started to write letters to community organizations all across the country. And one day, a small group of churches on the South Side of Chicago answered, offering me work with people in neighborhoods hit hard by steel mills that were shutting down and communities where jobs were dying away.

The community had been plagued by gang violence, so once I arrived, one of the first things we tried to do was to mobilize a meeting with community leaders to deal with gangs. And I’d worked for weeks on this project. We invited the police; we made phone calls; we went to churches; we passed out flyers. The night of the meeting we arranged rows and rows of chairs in anticipation of this crowd. And we waited, and we waited. And finally, a group of older folks walked in to the hall and they sat down. And this little old lady raised her hand and asked, “Is this where the bingo game is?” (Laughter.) It was a disaster. Nobody showed up. My first big community meeting — nobody showed up.

And later, the volunteers I worked with told me, that’s it; we’re quitting. They’d been doing this for two years even before I had arrived. They had nothing to show for it. And I’ll be honest, I felt pretty discouraged as well. I didn’t know what I was doing. I thought about quitting. And as we were talking, I looked outside and saw some young boys playing in a vacant lot across the street. And they were just throwing rocks up at a boarded building. They had nothing better to do — late at night, just throwing rocks. And I said to the volunteers, “Before you quit, answer one question. What will happen to those boys if you quit? Who will fight for them if we don’t? Who will give them a fair shot if we leave?

And one by one, the volunteers decided not to quit. We went back to those neighborhoods and we kept at it. We registered new voters, and we set up after-school programs, and we fought for new jobs, and helped people live lives with some measure of dignity. And we sustained ourselves with those small victories. We didn’t set the world on fire. Some of those communities are still very poor. There are still a lot of gangs out there. But I believe that it was those small victories that helped me win the bigger victories of my last three and a half years as President.

And I wish I could say that this perseverance came from some innate toughness in me. But the truth is, it was learned. I got it from watching the people who raised me. More specifically, I got it from watching the women who shaped my life.

I grew up as the son of a single mom who struggled to put herself through school and make ends meet. She had marriages that fell apart; even went on food stamps at one point to help us get by. But she didn’t quit. And she earned her degree, and made sure that through scholarships and hard work, my sister and I earned ours. She used to wake me up when we were living overseas — wake me up before dawn to study my English

lessons. And when I’d complain, she’d just look at me and say, “This is no picnic for me either, buster.” (Laughter.)And my mom ended up dedicating herself to helping women around the world access the money they needed to start their own businesses — she was an early pioneer in microfinance. And that meant, though, that she was gone a lot, and she had her own struggles trying to figure out balancing motherhood and a career. And when she was gone, my grandmother stepped up to take care of me.

She only had a high school education. She got a job at a local bank. She hit the glass ceiling, and watched men she once trained promoted up the ladder ahead of her. But she didn’t quit. Rather than grow hard or angry each time she got passed over, she kept doing her job as best as she knew how, and ultimately ended up being vice president at the bank. She didn’t quit.

And later on, I met a woman who was assigned to advise me on my first summer job at a law firm. And she gave me such good advice that I married her. (Laughter.) And Michelle and I gave everything we had to balance our careers and a young family. But let’s face it, no matter how enlightened I must have thought myself to be, it often fell more on her shoulders when I was traveling, when I was away. I know that when she was with our girls, she’d feel guilty that she wasn’t giving enough time to her work, and when she was at her work, she’d feel guilty she wasn’t giving enough time to our girls. And both of us wished we had some superpower that would let us be in two places at once. But we persisted. We made that marriage work.

And the reason Michelle had the strength to juggle everything, and put up with me and eventually the public spotlight, was because she, too, came from a family of folks who didn’t quit — because she saw her dad get up and go to work every day even though he never finished college, even though he had crippling MS. She saw her mother, even though she never finished college, in that school, that urban school, every day making sure Michelle and her brother were getting the education they deserved. Michelle saw how her parents never quit. They never indulged in self-pity, no matter how stacked the odds were against them. They didn’t quit.

Those are the folks who inspire me. People ask me sometimes, who inspires you, Mr. President? Those quiet heroes all across this country — some of your parents and grandparents who are sitting here — no fanfare, no articles written about them, they just persevere. They just do their jobs. They meet their responsibilities. They don’t quit. I’m only here because of them. They may not have set out to change the world, but in small, important ways, they did. They certainly changed mine.

So whether it’s starting a business, or running for office, or raising a amazing family, remember that making your mark on the world is hard. It takes patience. It takes commitment. It comes with plenty of setbacks and it comes with plenty of failures.

But whenever you feel that creeping cynicism, whenever you hear those voices say you can’t make a difference, whenever somebody tells you to set your sights lower — the trajectory of this country should give you hope. Previous generations should give you hope. What young generations have done before should give you hope. Young folks who marched and mobilized and stood up and sat in, from Seneca Falls to Selma to Stonewall, didn’t just do it for themselves; they did it for other people. (Applause.)

That’s how we achieved women’s rights. That’s how we achieved voting rights. That’s how we achieved workers’ rights. That’s how we achieved gay rights. (Applause.) That’s how we’ve made this Union more perfect. (Applause.)

And if you’re willing to do your part now, if you’re willing to reach up and close that gap between what America is and what America should be, I want you to know that I will be right there with you. (Applause.) If you are ready to fight for that brilliant, radically simple idea of America that no matter who you are or what you look like, no matter who you love or what God you worship, you can still pursue your own happiness, I will join you every step of the way. (Applause.)

Now more than ever — now more than ever, America needs what you, the Class of 2012, has to offer. America needs you to reach high and hope deeply. And if you fight for your seat at the table, and you set a better example, and you persevere in what you decide to do with your life, I have every faith not only that you will succeed, but that, through you, our nation will continue to be a beacon of light for men and women, boys and girls, in every corner of the globe.

So thank you. Congratulations. (Applause.) God bless you. God bless the United States of America. (Applause.)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com