The scariest part of Emily Vorland’s relatively uneventful 2009 deployment to Iraq was that the enemy wore Army green, just like she did. When a higher-ranking male officer sexually harassed her, her commander told Vorland to file a formal complaint. So she did. Lieutenant Vorland was grateful when higher-ups ordered her alleged abuser to stop contacting her. But as the investigation continued, Vorland says the Army seemed to shift its focus to her.

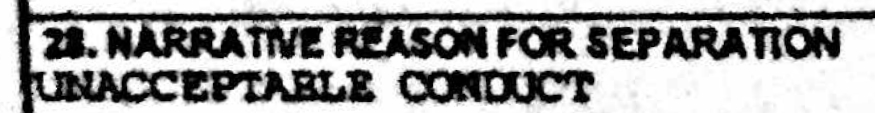

It concluded she had “acted inappropriately,” engaged in consensual sex and was lying about it. A lesbian, she was concerned that her best defense was one that would end her military career because the “don’t ask, don’t tell” rules were still in place. The Army used her acknowledgement that she should have been more careful in detailing what happened to generate a letter of reprimand, which it used to boot her out with a general discharge for “unacceptable conduct,” after her unit returned to its Texas base in 2010.

Her less-than-honorable discharge kept her out of the National Guard, barred her from transition assistance, and denied her six months of free post-military health care. Finding a job proved tough, because she’d be asked for her discharge papers to prove she had served. “So I avoided jobs where they wanted to see your DD-214,” she says, referring to the Pentagon’s discharge form.

“I wasn’t happy about it, but at the time I didn’t see it as being very impactful,” she says. “There was this sense of ‘Just go to the discharge review board and you’ll be fine,’” she remembers hearing about upgrading her discharge. That’s when she ran into an even more implacable Army foe: the stacked maze veterans must endure to try have their discharges upgraded.

Vorland got a preview of the process as she waited to appear before such a board in Dallas in 2013 and heard shouting from inside the closed-door hearing, where a young vet was seeking an upgraded discharge. Suddenly, rescue personnel rushed into the building. “The guy apparently became so undone that he threw up in the hearing,” Jo Ann Merica, Vorland’s lawyer, says. “We saw him carried out to an ambulance.”

The process that unfolded once Vorland and her lawyer got inside the hearing room also made them sick. The panel’s chairwoman, an Army colonel, was joined by several other Army personnel via video. “They just continued the retaliation, going into who I was as a person and asking me if I’d lied,” Vorland says. Merica was “flabbergasted” by what she called a “witch hunt”—where her pro-bono client was the one at the stake. “It was a weird atmosphere, and seemed like they already had their decision made,” says Chief Warrant Officer Norma Garza, a UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter pilot who was Vorland’s roommate in Iraq and testified for her at the hearing. “She got discharged from the Army when she wasn’t at fault.”

“I’ve been in a lot of courtrooms before, and I’ve appeared before some very cranky federal judges,” says Merica, who handled the case pro bono. “But I was almost immediately disabused of the notion that this hearing was going to be conducted with the same type of decorum.”

Less than two weeks later, the board rejected Vorland’s petition.

Even as the military scrambles under congressional pressure to prevent future cases of sexual abuse, past victims are suffering for having stood up for themselves. Thousands of victims have been pushed out of the service with less-than-honorable discharges, which can leave them with no or reduced benefits, poor job prospects and a lifetime of stigma. Worse, when they try to rectify their situation, as Vorland did, fewer than 10% of them succeed, the advocacy group Human Rights Watch estimates (the Pentagon doesn’t compile such data).

“Military personnel who report a sexual assault frequently find that their military career is the biggest casualty,” the group says in a new report. It spoke to 163 veterans ousted from the military between 1966 and 2015 after complaining about sexual abuse, ranging from harassment to rape. “Our interviews suggest that all too often superior officers choose to expeditiously discharge sexual-assault victims rather than support their recovery and help them keep their position,” the study says.

“For far too many years, the service members and veterans who have survived military sexual trauma have been re-victimized by improper discharges and an ineffective and discriminatory claims-review process,” Connecticut Sen. Richard Blumenthal, the senior Democrat on the veterans affairs committee, tells TIME. “These survivors deserve better.”

A Pentagon inspector general’s report released Tuesday made clear that the military process for those leaving the service after complaining about sexual abuse could use tidying up. Two of every three personnel files the IG requested from the services were incomplete, and one of every five could not be found. The IG conducted the inquiry after Congress said, in last year’s defense bill, that it was “concerned about early discharges of service members who have made a report of sexual assault.”

The Pentagon process for reviewing discharges is stacked against the discharged, through a byzantine and skewed process that, by default, contends their ouster was proper. “This is one of the weakest links in the American system of justice,” says Eugene Fidell of Yale Law School, a former president of the National Institute of Military Justice who says he has represented “scores” of veterans seeking upgraded discharges.

The Navy, for example, says it “will always presume” the original discharge was “correct,” and that unhappy ex-sailors must produce “clear and substantial evidence” the service was wrong. “Many service members reported being singled out for discipline for minor infractions following a sexual assault report in an effort, they believe, to create a record justifying a misconduct discharge,” the study says.

Responding to the report, the Pentagon says recent changes mean “liberal consideration” will be given to veterans seeking upgraded discharges, including those alleging sexual abuse. The Defense Department gives the services “wide latitude in ensuring their high standards are met, but provides oversight through the extensive procedural requirements and appeal options available to service members who face separations,” says Air Force Major Ben Sakrisson, a Pentagon spokesman.

Such less-than-honorable discharges are on the rise. About 125,000 veterans who served in Afghanistan and Iraq have such “bad paper” discharges that deny them VA benefits. That translates into a rate nearly double as those who served in Vietnam, and four times as likely as those who served in World War II, according to a recent report from Swords to Plowshares, a veterans advocacy group.

Military discharges fall into several categories. More than 85% are “honorable” discharges. One step down is a “general under honorable conditions” discharge, followed by one issued “under other than honorable conditions.” The worst are “bad conduct” and “dishonorable” discharges, generally stemming from courts martial, and can’t be changed by review boards. The Human Rights Watch report also notes that many sexual-assault survivors are booted out for “personality disorders.” Between 2001 and 2010, there were more than 31,000 of these discharges. Such blemished discharges have been linked to homelessness, imprisonment and suicide. Poor discharges also can deny veterans suffering from mental distress resulting from sexual assault from receiving the care from the Department of Veterans Affairs (about 33% of sexual-assault victims experience post-traumatic stress disorder, compared to an estimated 15% of combat veterans).

Heath Phillips enlisted in the Navy in 1988 at 17, and says repeated sexual assaults by fellow sailors forced him to go absent without leave from the USS Butte, an ammo-supply ship. “I was so messed up I tried hanging myself in a storage room,” he says. “You think as a sailor I would know how to tie a knot, but I didn’t know how to tie a slipknot.” Ultimately, the service gave him a choice: six months’ confinement aboard ship with his abusers, or his signature on discharge papers that would get him off the ship and out of the Navy. “I felt that if I stayed aboard the ship, I’d be killed, or kill one of them,” Phillips says. “I would have signed a deal with the devil to get off that ship.”

He says a Navy lawyer assured him that his other-than-honorable-discharge would be automatically upgraded after six months, but it never happened. “I was a teenager and very naïve,” says Phillips, now 44. “I didn’t know any better.” Phillips, suffering from PTSD, spent more than a decade mired in liquor and drugs. Now married with six children (“none of them want to go into the military”) and living in upstate New York, Phillips has filed written petitions with the Navy twice seeking to upgrade his discharge without success. “We always bring up the sexual assaults,” he says, “but they never do.”

Veterans can seek an upgraded discharge from discharge review boards, either in writing or in person, within 15 years of leaving the military. Beyond that time frame, or if the military-staffed review board has denied an upgrade, the veteran can file an appeal with the service’s board for the correction of military records. But the process is confusing. The boards rarely hold hearings and lack full documentation of their proceedings, which makes prevailing (most vets do not have lawyers) difficult.

While the boards’ decisions can be appealed to federal courts, only a handful of vets do so, because of the financial and emotional toll involved. Only 56 former soldiers appealed the tens of thousands of decisions made by the Army’s Board for the Correction of Military Records between 2008 and 2013; the courts reversed 12, at least in part. The chance of a court reversing board decisions “is so negligible and deferential as to be nearly non-existent, providing little incentive for boards to create credible decisions that can withstand scrutiny,” Human Rights Watch concludes.

The boards, created by Congress in 1946, make a certain amount of sense. Commanders don’t have time to deal with troublemakers, especially on the front lines, and are given leeway to force troops out. But that makes the boards’ oversight, acting as a check on commanders’ authority, critical. “In the civilian world, you have protections against being unfairly fired, but that doesn’t happen in the military,” says Sara Darehshori, the report’s author. The boards for the correction of military records, staffed by civilians, are supposed to provide such protection, “but the process has been overtaken by military staff who do all the decision-making for the boards’ rubber stamp.”

Human Rights Watch concludes that there needs to be wholesale changes in how the military reviews such discharges, including the right to hearings where military personnel can tell their stories. Cases should be recorded, summarized and available to petitioners to help guide their appeals.

Back in Texas, veteran Vorland works as a physical therapist in Austin, 70 miles south of Fort Hood, where her Army career ended more than five years ago. Despite the passage of time, her nightmare continues. The Army insists she repay $4,000 of the ROTC grant she used to attend the University of Iowa due to her early ouster.

“I still feel pride in my service, but there’s a sense of humiliation,” Vorland says. “I did the right thing, so how has this happened?” However, she savors small victories. The Texas Department of Motor Vehicles, citing her bad paper, denied her a veteran’s license plate. But she convinced the DMV she’d earned one, which is now proudly fastened above the rear bumper of her 2008 Nissan Sentra.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Canada Fell Out of Love With Trudeau

- Trump Is Treating the Globe Like a Monopoly Board

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- See Photos of Devastating Palisades Fire in California

- 10 Boundaries Therapists Want You to Set in the New Year

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Nicole Kidman Is a Pure Pleasure to Watch in Babygirl

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com