Headlines coming out of Burma have been largely positive this year, with the country’s first democratically elected government in decades taking the reins in late March following a sweeping election victory in November.

Yet U.S. President Barack Obama announced Tuesday that the situation in Burma, officially known as Myanmar, “continues to pose an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States.”

While Obama praised ongoing progress in the country, such as the release of political prisoners and child soldiers, and steps to improve labor standards, he raised serious concerns over the continued grip of power the military has in government, as well as ethnic civil wars and human-rights abuses.

Recent U.S. policy toward Burma has really been all about increasing engagement in a country that rarely produces good news stories. Presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton touts the country’s transition from brutal military rule as a major success of her time as Secretary of State. Her successor John Kerry will travel to Burma on May 22, as the State Department announced last week, “to signal U.S. support for the new democratically elected, civilian-led government and further democratic and economic reforms.”

Read More: 5 Challenges Facing Burma’s New Civilian Government

In keeping with that mood, seven state-run companies and three state banks were on Tuesday removed from the blacklist of specially designated nationals (SDNs) — companies and individuals with whom U.S. companies are barred from doing business. The Treasury also signaled a relaxation of measures that have restricted financial transactions involving Burma, and extended indefinitely an exemption that allows American firms to trade through the country’s biggest port and airport, which are both owned by controversial local tycoon Steven Law.

A trade embargo against Burma was mostly lifted in 2012, as the country began its transition to democracy, but bans on the lucrative trade in jade — which is mostly sold to China — and rubies remain, as do restrictions on specific businesses that propped up military rulers during years of isolation. (Six more companies owned by Law, the son of alleged Golden Triangle drug trafficker Lo Hsing Han, were added to the blacklist list Tuesday.)

The simultaneous give and take of sanctions reflects the complicated events now taking place in Burma that have fueled heated debate in recent weeks over whether the country should remain one of only 20 or so states against whom the U.S. has a specific sanctions program.

On the surface, Burma looks like a beacon of self-determination in an increasingly authoritarian region. Power was transferred smoothly to the election winners and Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi is now the government’s de facto leader in the self-created role of State Counselor. Investment is up, and Burma is experiencing Asia’s highest rate of economic growth.

Read More: Burma’s Transition to Civilian Rule Hasn’t Stopped the Abuses of Its Ethnic Wars

Against this backdrop, business lobbyists have called for the sanctions regime to be lifted entirely. They argue that it’s handicapping American companies in one of the last frontier economies (the country is rich with minerals, timber and oil and gas, and wages remain low enough to attract manufacturers looking for cheap workers). Calls to scale back sanctions against Burma have won some support in diplomatic circles, and even some within the Obama Administration admit that overusing them could damage the U.S.’s status as the center of the global financial system.

Eric Rose, a U.S. lawyer at the Rangoon-based Herzfeld Rubin Meyer & Rose law firm, told TIME that Tuesday’s changes did not do enough to ease the burdens on U.S. companies trying to deal with Burma. Leaving most of the powerful business tycoons — known locally as cronies — on the blacklist would continue to impede much-needed investment, he said. “The partial embargo against over 150 SDN-listed [Burmese] businesses and individuals, which control over 70% of [Burma’s] economy, continues unabated despite the loud and clear message of change given by the voters in November,” Rose said.

Burma Counts Down to Elections But Democracy Remains a Distant Dream

Peter Kucik, a former Treasury official who now advises companies on Burma for Inle Advisory Group, said targeted sanctions like the SDN list enabled the U.S. to influence developments overseas. But regular delistings were necessary to make sanctions effective as an incentive, he says. “While it takes time to investigate and assess each removal case, there must be a reasonable timetable for entities seeking relief,” he says by email.

Countering arguments calling to free up trade with Burma are human-rights advocates, who have been urging Obama to renew sanctions, saying that they remain one of the few proven tools in the diplomatic arsenal to tackle ongoing abuses. That call has been echoed by U.S. representatives on both sides of Congress.

Read More: Why Burma Is Trying to Stop People From Using the Name of Its Persecuted Muslim Minority

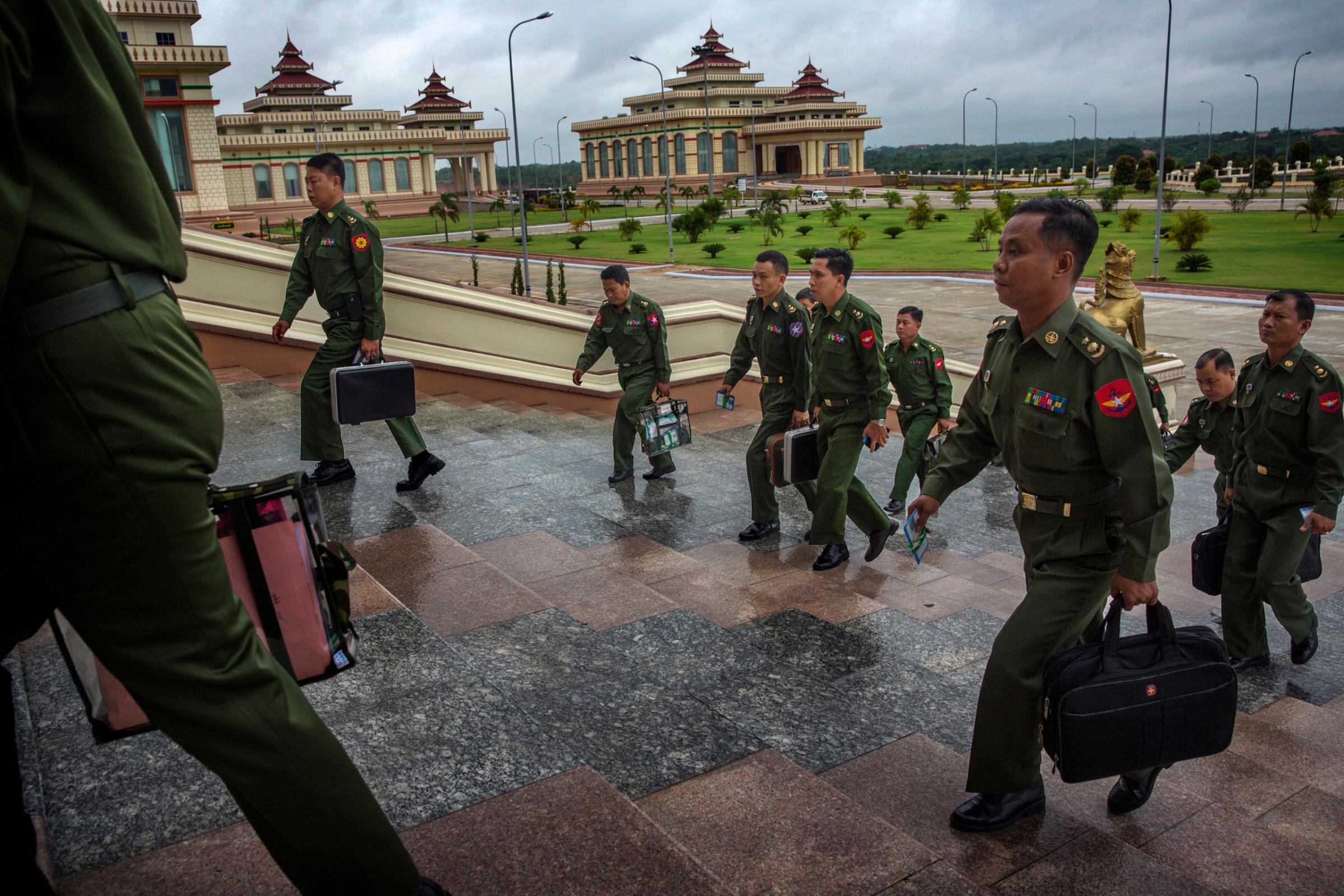

“It’s pressure applied to different targets within the country,” says Tom Andrews, a former Congressman and the president of the Washington, D.C.–based United to End Genocide. He stresses that Suu Kyi is confronting a constitutionally empowered military, with serving and former soldiers placed throughout the government, who wield serious economic clout through military-owned companies.

Suu Kyi, who spent the better part of the 1990s and 2000s under house arrest, is thought to have encouraged Western sanctions against the former junta. She has not spoken publicly on the issue recently, but officials in Washington told Reuters that Suu Kyi supported extending most sanctions.

Andrews says sanctions should also be used to pressure Suu Kyi herself. She has not spoken out about the oppression of the Rohingya, a persecuted Muslim ethnic group numbering more than 1 million who are denied citizenship by the Burmese state. Suu Kyi has even instructed Scot Marciel, the American ambassador in Rangoon, not to refer to the group as Rohingya — a name that’s not officially recognized in Burma.

“It’s extremely important for pressure to be maintained on the government of [Burma],” Andrews tells TIME, lamenting that the Obama Administration had not done more to target sanctions at human-rights abusers. “In key areas, we are seeing things going in the wrong direction.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Simon Lewis at simon_daniel.lewis@timeasia.com