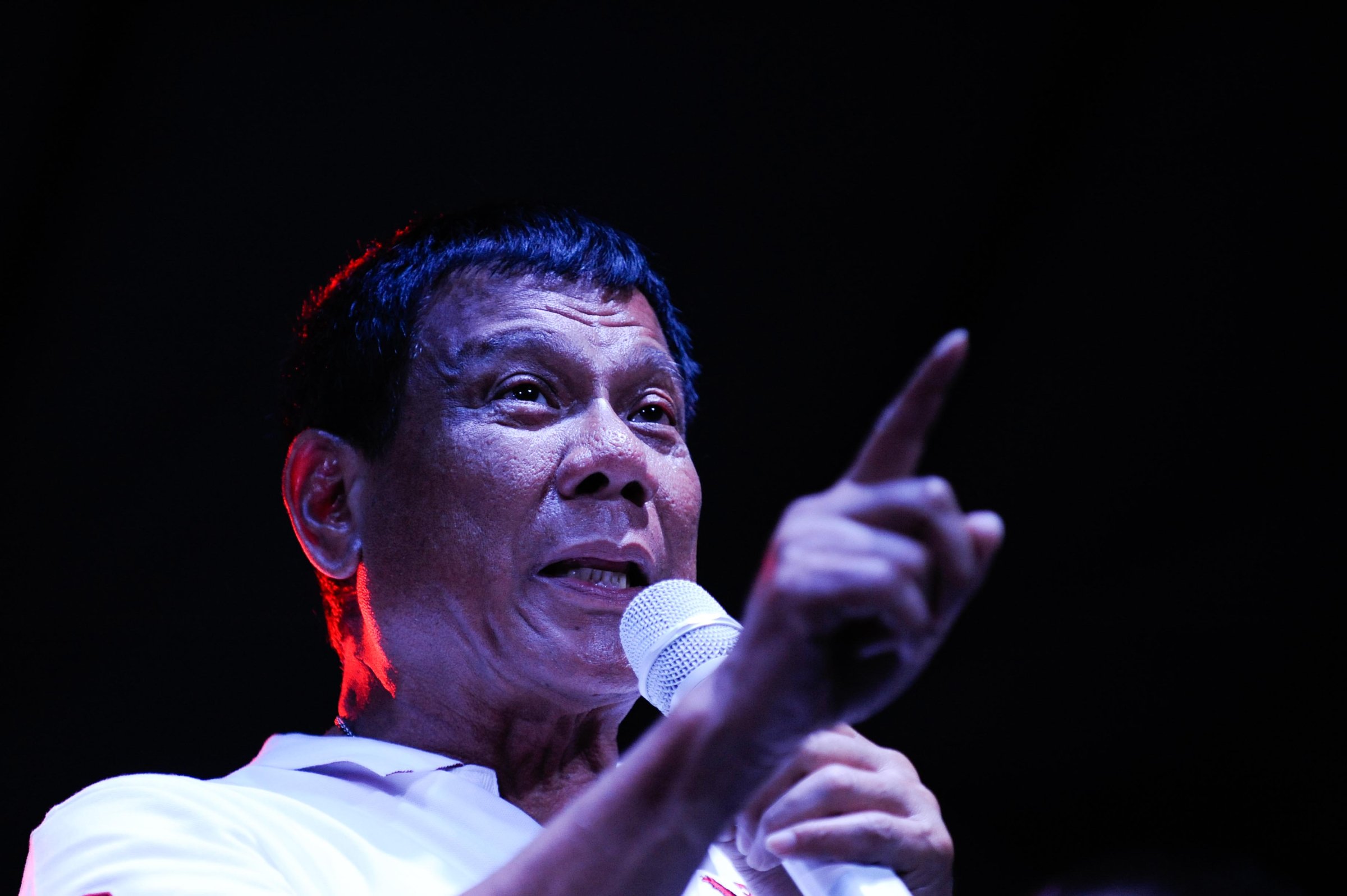

He jokes about rape, threatens to “butcher” criminals in front of human-rights advocates, and once called Pope Francis a “son of a whore” for clogging Manila traffic during a papal visit. But on May 9, Rodrigo Duterte was elected the 16th President of the Philippines, having mesmerized voters with his promise to purge the Southeast Asian nation of drugs, crime and corruption within six months. “It’s with humility, extreme humility, that I accept this, the mandate of the people,” Duterte, 71, told reporters after winning 38% of the popular vote in a five-candidate race.

Humility is not a quality usually associated with Duterte. As mayor of Davao, a sprawling city of 1.5 million on Mindanao Island, he developed a fearsome reputation for fighting crime. When he first took office, some 30 years ago, Davao was a no-go zone for many Filipinos—a cauldron of insurgents, jihadists and gangsters. Duterte turned the city around. He would personally patrol streets after dusk, checking up on police officers, dropping by jails to scold habitual offenders and dispensing pocket change to streetwalkers or the otherwise hard-up. His antics drew comparisons with rule-flouting Hollywood vigilantes such as “the Punisher” and “Dirty Harry.” “Davao is safe because of him,” says first-time voter Bless Golez, 18, an accounting-technology student and resident. “We want him to do the same for the rest of the Philippines.”

Duterte’s victory is not just a domestic story. The Philippines is a key U.S. ally standing up to Chinese expansion in the South China Sea, where both Beijing and Manila claim the resource-rich Spratly Islands. President Benigno Aquino III, who was ineligible for reelection after a single six-year term, recently agreed to ramp up U.S. troop rotations on Philippine military bases. Manila is vital to Washington’s “rebalancing” to Asia.

Is Duterte suited to leading so pivotal a nation? During his campaign he joked that he “should have been first” in the 1989 rape of a “beautiful” Australian missionary. He said he’d “kill” his own children if they dabbled in drugs, and told a women’s-rights group to “go to hell” for reporting him to the national human-rights commission for what he said about the rape.

But if Duterte is politically outrageous, he is no outsider. Southeast Asia’s most vibrant democracy is dominated by a network of powerful clans. And though Duterte portrays himself as the antidote to entitlement and privilege, his father was governor of Davao province, and his daughter is succeeding him as mayor. “Like in any capitalist country, we just have to accept the fact that the influence and the power of the rich cannot be constrained,” outgoing Vice President Jejomar Binay, who was also running for the presidency, tells TIME.

The President-elect is also identified with death squads. On local television he read out the names of petty criminals, warning them to reform their ways or face dire consequences. The bloated bodies of some of those named later turned up riddled with .45 ACP or 9-mm bullets. International human-rights groups say that several hundred innocent people are among those summarily executed, a tactic mimicked by other towns across the country.

Duterte both denies accusations of mass murder and boasts on the stump about gunning down hoodlums. “If I make it to the presidential palace, I will do just what I did as mayor,” he told a sea of 300,000 supporters in Manila on May 7. “All of you who are into drugs, you sons of bitches, I will really kill you. I have no patience, I have no middle ground, either you kill me or I will kill you idiots.”

For many non-Filipinos, Duterte’s populist rise may be perplexing, given that the archipelago long dubbed the “sick man of Asia” is now one of the region’s best-performing economies. Annual growth stands at around 6.1%, inflation at less than 2% and the young, English-speaking population is at a demographic sweet spot for foreign investment. Plus, the country is no longer dogged by coup rumors. (As recently as 2007, renegade soldiers seized Manila’s five-star Peninsula Hotel.)

But the gains are not widely felt. Despite Aquino’s inroads against corruption and the budget deficit, many complain that the current boom lacks inclusiveness, with a quarter of the 100 million population below the poverty line. Manila does not feel like a flourishing metropolis, awash as it is with tumbledown shanties. Conditions are even worse in rural areas, where farmers contend with alternating typhoons and droughts. Infrastructure remains dismal across much of the country, undermining efforts to build a manufacturing economy.

In the end, there was only muted support for moderate candidates. Manuel “Mar” Roxas, a former banker and Cabinet member who was Aquino’s chosen pick, struggled to charm voters after a gaffe-ridden early campaign. And Senator Grace Poe, a foundling adopted by Philippine movie legend Fernando Poe, was hampered by residency issues.

Duterte’s populist rhetoric and public crudity inevitably drew comparisons with Donald Trump, the presumptive U.S. Republican presidential nominee. But Duterte’s three decades in public service—he started as a prosecutor—and steadfast support for minorities, make the parallel problematic. A Catholic who lives in a modest three-bedroom home, Duterte sends donations to Islamic charities and fiercely defends the nation’s marginalized Moro Muslims. Despite government peace deals with Mindanao’s two main armed groups, splinter cells continue to wage a guerrilla war that has claimed some 120,000 lives since the 1970s. Duterte advocates the devolution of power through federalism. “Sixty years ahead of when Magellan landed and claimed these islands for King Philip of Spain, Islam was already firmly implanted here,” he says. “They are just claiming what is their legitimate right.”

Duterte is adopting a conciliatory approach too with China. Aquino took Beijing to an international court in the Hague over competing territorial claims in the South China Sea. Duterte, arguing against antagonizing the superpower, instead has said he would be in favor of joint exploration of oil beneath the atolls. If that worries Washington, he’s less concerned. When the U.S. and Australian ambassadors condemned Duterte’s rape remark, he responded by threatening to sever diplomatic ties. “China will play the long game and entice the new President into resuming high-level contact,” says Carlyle Thayer, emeritus professor at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

For the present, Duterte is focused on home. At a press conference at the close of polling, he pledged to make up with his fellow candidates. “Let us begin the healing now,” he said. But a few minutes later, Duterte was on his feet, black marker pen in hand, scrawling a single word over the campaign backdrop: STOP. “I would like people in government to memorize this one word,” he said, eyes steely. “Do not oppress the people. Stop your corruption.” The Punisher was now the President.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlie Campbell/Davao at charlie.campbell@time.com