On May 16, 1966—precisely 50 years ago Monday—the Central Committee of China’s Communist Party issued a circular that would come to be known by that very date. The nation “must not entrust” academics, experts, journalists, artist and other “representatives of the bourgeoisie who have sneaked into the Party” with “the work of leading the Cultural Revolution.”

The May 16 Circular is widely seen as the official beginning of the Cultural Revolution in China, a period of terror during which Mao Zedong led the Party in persecuting anyone who might be seen as counter-revolutionary. As TIME put it that summer, Mao “aimed to blot out not only all traces of foreign influence, but to tear out China’s own cultural and historical roots as well.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

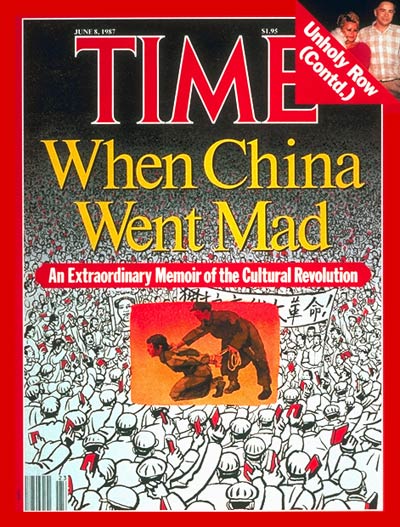

In 1987, TIME published a lengthy excerpt from Nien Cheng’s memoir Life and Death in Shanghai, the tale of her experience as a target of that prosecution. On the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution, her story is worth revisiting as a first-hand account of what happened.

Cheng worked for the oil company Shell until it pulled out of China in 1966, and ended up imprisoned for six-and-a-half years. When her story begins here, she has received an unexpected visit at home from a stranger and a man, Qi, who worked with the union at Shell:

”’We have come to take you to a meeting,” Qi said.

”You have been so slow that we will probably be late,” the other man added. ‘

‘What’s the meeting about?” I asked.

”There’s no need to ask so many questions,” the activist said. ”We would not be here if we did not have authority. All the former members of Shell have to attend this meeting. It’s very important. Don’t you know the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution has started?” The servants looked anxious as I left. We all knew that since Mao took over, innumerable people had left their homes during the political campaigns and never come back.

At the technical school, the target of the meeting was Tao Feng, the former chief accountant of our office. After several hours of speeches denouncing Shell and the ”running dogs of imperialism,” Tao Feng was led into the room wearing a tall dunce cap made of white paper with COW’S DEMON AND SNAKE SPIRIT written on it. (In Chinese mythology, these are evil spirits that can assume human forms to do mischief. Mao had first used this expression during the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957 to describe the intellectuals, many of whom were sent to labor camps for having taken up the Chairman’s own invitation to offer frank and constructive criticism of the Communist Party.)

In the office, Tao Feng was always full of self-assurance. Now he looked nervous and thoroughly beaten. He had lost a great deal of weight and seemed years older than only a few months ago. The young people behind me snickered. A man pushed a chair forward and told Tao Feng to stand on it. When he did and stood there in a posture of subservience in his tall paper hat, the snickers became uncontrolled laughter.

Someone in a corner of the room stood up. Holding up the Little Red Book of Mao Tse-tung’s quotations, he led the assembly in shouting slogans:

”Down with Tao Feng!” ”Down with the running dog of the imperialists!” ”Long live our great leader Chairman Mao!”

I was shocked to see Tao Feng raise his fist and shout with gusto the same slogans, including those against himself.

”Tao Feng will now make his self-criticism,” the man leading the meeting announced. Without lifting his eyes, Tao read a prepared statement in a low and trembling voice. He admitted all the ”crimes” listed by the speakers. He expressed regret for having worked for a foreign firm for more than 35 years and said he had wasted his life. He said he was ashamed he had been blinded by capitalist propaganda.

After the meeting, the man in charge took me aside. ”You must make a determined effort to emulate Tao Feng and do your best to reform,” he warned.

”I’m not aware of any wrongdoing on my part,” I said.

”Perhaps you’ll change your attitude when you’ve had time to think things over,” said a second man. ”If you try to cover up for the imperialists, the consequences will be serious.”

Read the rest, here in the TIME Vault: An Extraordinary Memoir of the Cultural Revolution

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com