Carl Mydans credited his camera with getting him a job as one of LIFE Magazine’s first photographers.

That idea may sound obvious, but—as Mydans expressed it in a 1992 oral-history interview—he meant it literally. Mydans was working as a writer for The American Banker, a special-interest publication, in the early 1930s. On his lunch break, he would go out and take pictures of street scenes. One day, he happened to see a man speaking on Wall Street on an actual soapbox; the man turned out to be Eugene Daniell, a rabble-rouser famous for having gotten tear gas into the ventilation system at the New York Stock Exchange. Thinking his pictures of Daniell might be newsworthy, Mydans tried to sell them to newspapers and wire services. The only publication that bit was TIME—and the image of Daniel that ran in the April 1, 1935, issue became Mydans’ first published photograph.

But the camera, and not just the photo, caught the eye of the editor at TIME. Mydans—who was born May 20, 1907—used a small 35-mm. at a time when most photographers were still shooting with much larger cameras. A smaller camera meant the photographer could move around more easily, capturing the world as it was spinning. The early adopters of 35-mm. technology were just the people Time Inc. had in mind for something they were calling “Project X.” That project would turn out to be the new LIFE Magazine, which launched in 1936. Mydans came on staff almost immediately.

“Making pictures and telling stories with my camera has been the center of my life ever since,” Mydans said in 1992. That life, with the camera at its center, would prove to be one of the 20th century’s most fascinating.

MORE: LIFE With MacArthur: The Landing at Luzon, the Philippines, 1945

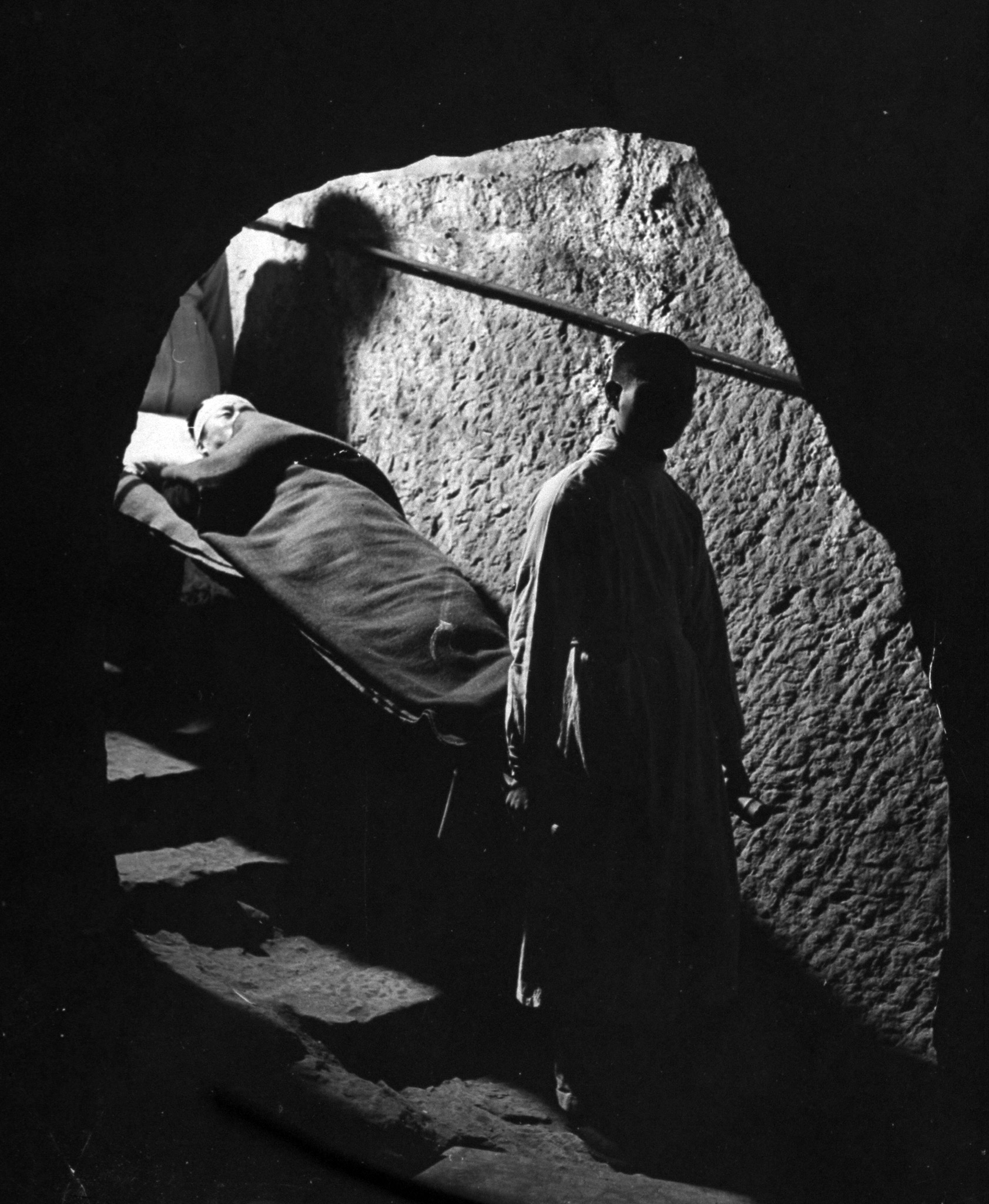

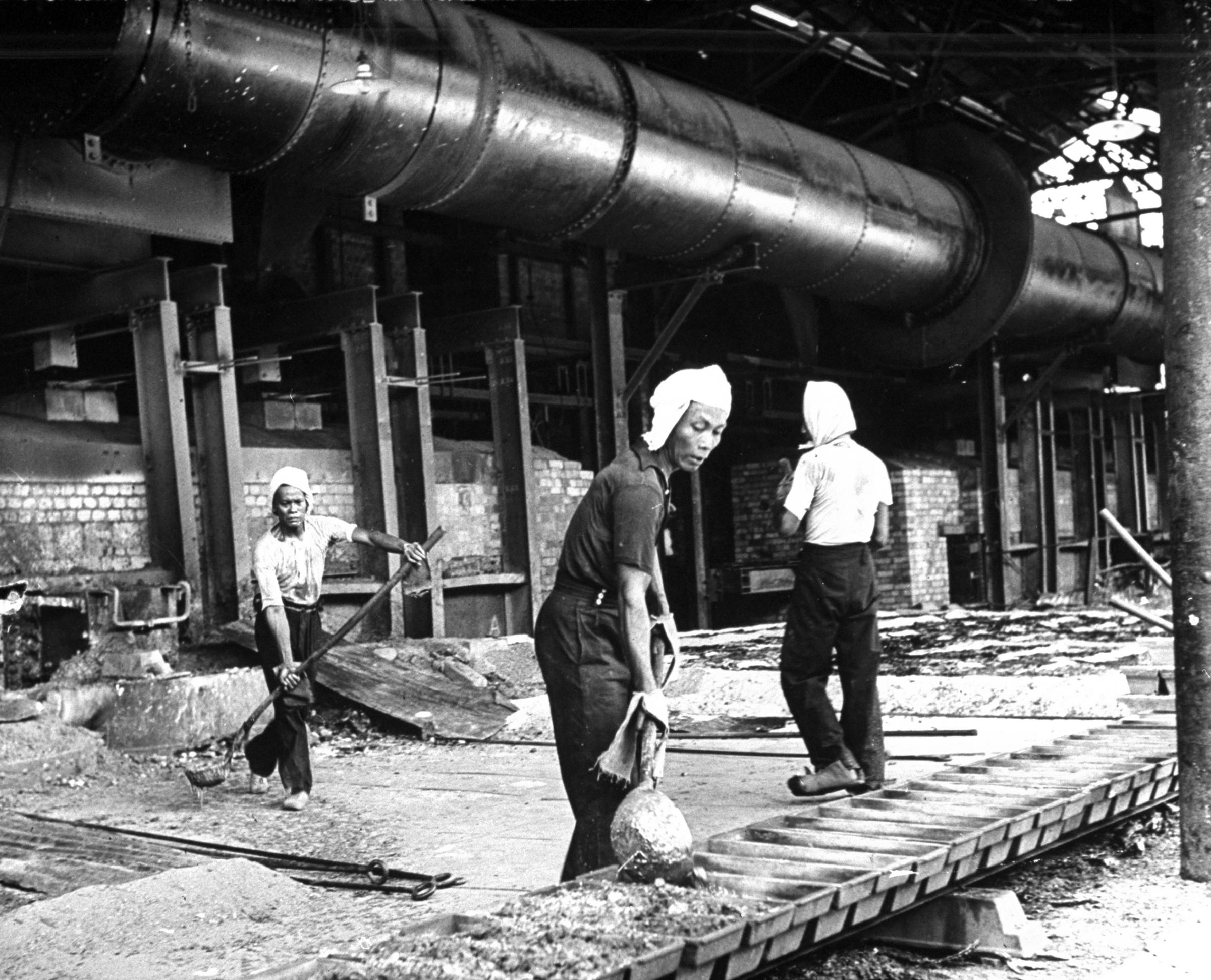

Though Mydans’ first assignments for LIFE were softer domestic stories, he had a way of colliding with world news, as these photographs from LIFE’s archives make clear. Shortly after he met his wife Shelley, who was a LIFE researcher, at a company holiday party in 1937, World War II started. The two were off to France—with a pit stop for Mydans to have an emergency appendectomy on the way—and they would barely stop moving for the rest of their lives.

As TIME put it in a review of his 1959 book More Than Meets the Eye, “Mydans, living and working in a time of violence, [saw] more of history than most men.”

MORE: JFK’s Assassination: Portrait of an Era When Newspapers Mattered

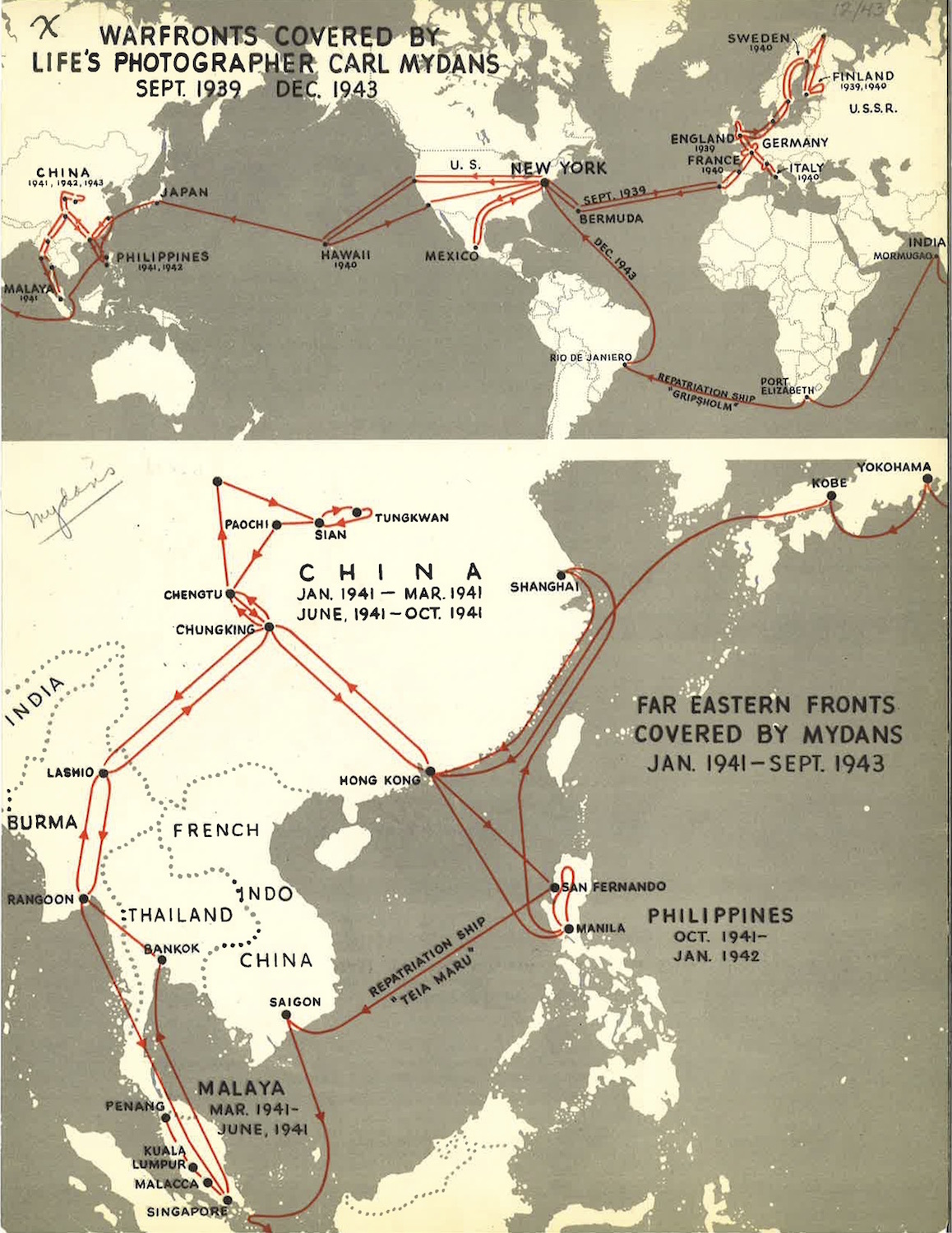

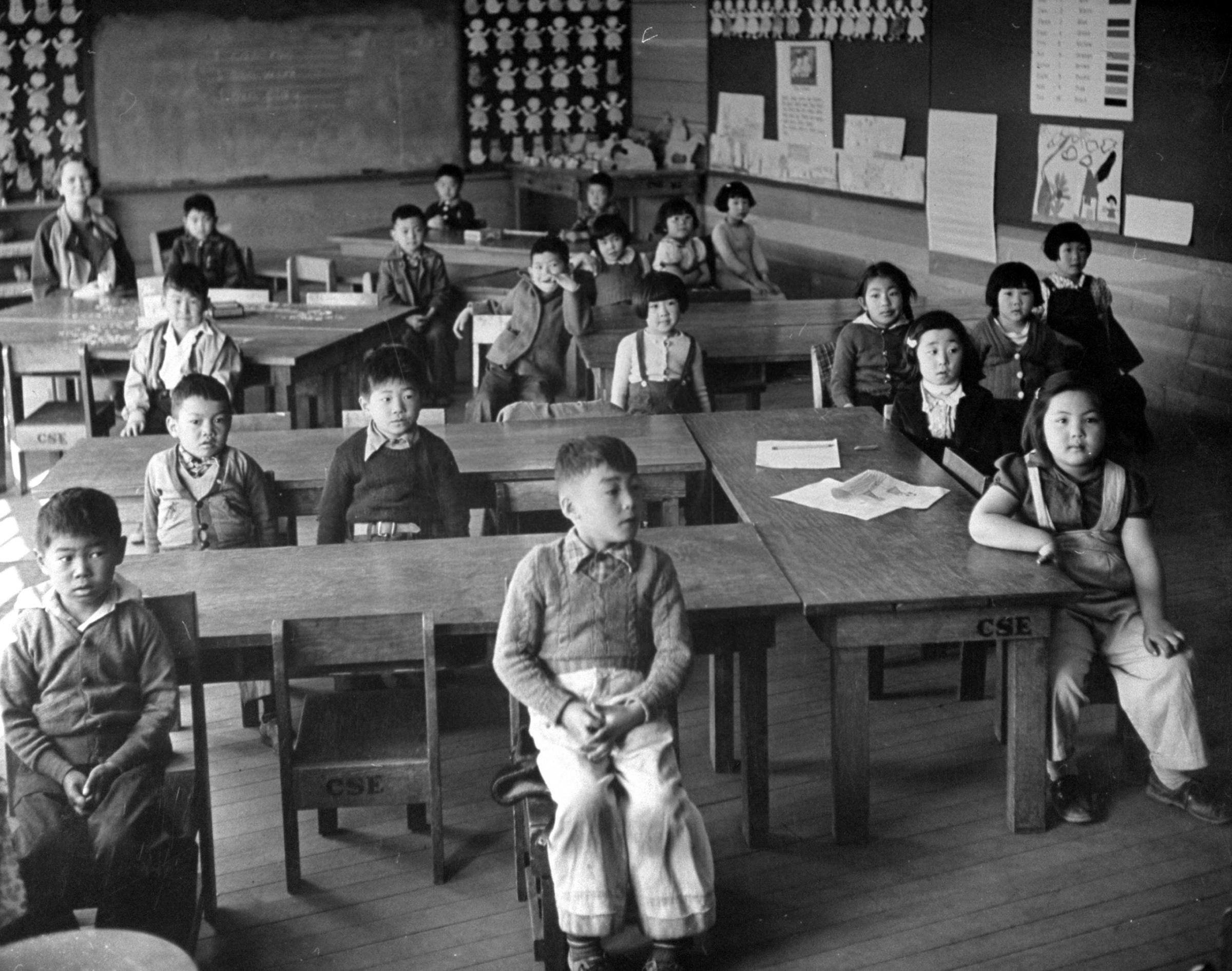

During World War II, Mydans worked on the Finnish-Russian border and in Sweden, Britain, Italy, France, China, Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines. At one point, he was mistaken for a German paratrooper, accused of being a spy and arrested. When the Philippines were seized by the Japanese, Carl and Shelley were trapped, first interned on a university campus and later in China, prisoners of war for nearly two years. After they were repatriated in 1943, they hardly paused before returning to the field. Carl Mydans would be one of three American correspondents on board Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s ship for his famed return to the Philippines, an episode that produced one of the photographer’s best known shots, and he captured the wreck that was Hiroshima only two weeks after the bomb was dropped.

The 1945 Battle of Luzon, during which MacArthur led the Allies to victory in the Philippines, highlighted how close he was to the news: Mydans accompanied the troops liberating prisoners of war at camp Santo Tomas, the very place where he and his wife had been interned. The memorable headline in LIFE quoted one of the prisoners he saw rescued: “My God, it’s Carl Mydans!”

The end of World War II did not mean an end to Mydans’ work, a fact he would explore in The Violent Peace, a 1968 book he co-wrote with his wife about the post-war world. Not only did war continue (Mydans covered the Korean War for LIFE) but, even without a battlefield, the world was unsettled—sometimes literally, as during the earthquake he covered in Japan in 1948. Serving as Tokyo Bureau Chief and Moscow Bureau Chief, he worked for LIFE until the magazine ceased weekly publication in 1972, after which he worked mostly for TIME.

MORE: World War II in Color: The Italian Campaign and the Road to Rome

Mydans died in 2004, remembered by his friends and colleagues as a man who had witnessed the worst of humanity but remained to the end gentle and friendly and a consummate professional. The camera had gotten him a job at LIFE, and it had shaped the arc of his own life. And, as his body of work clearly shows, he did the camera justice.

“Marked by pride and delight and excitement in what we were doing under the new name ‘photojournalists,'” he once wrote in a draft for an unpublished memoir, “we became storytellers and recorders of our times in pictures.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com