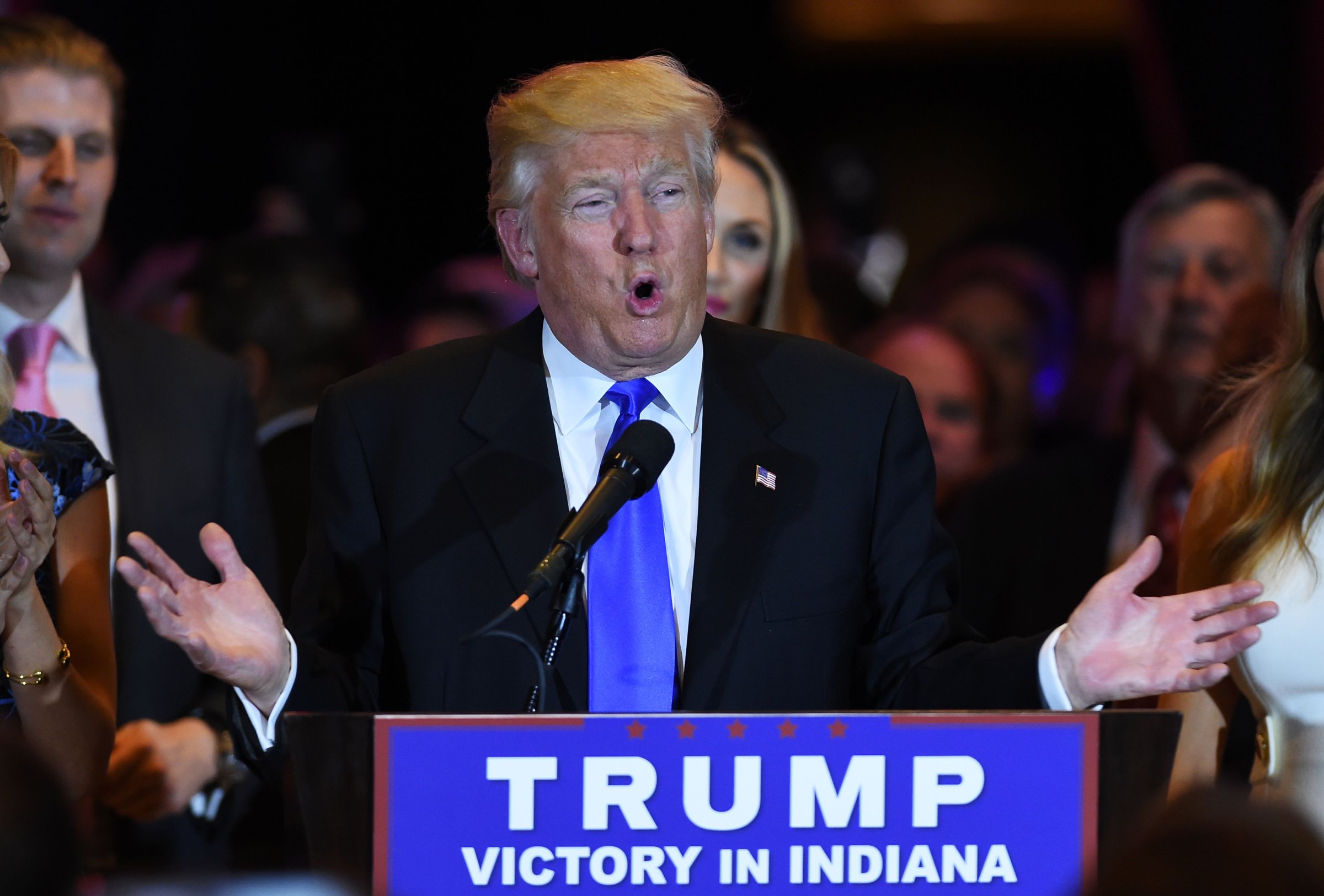

Donald Trump is running a presidential campaign that often seems to be more about projecting strength than offering specific policy positions. Trump presents himself to voters as a “strong man” type who would deport millions of people currently living in the U.S., bar Muslims from entering the country, shut down mosques and perhaps set up a national database to track Muslims.

Given that Trump is now the presumptive Republican nominee, it’s worth considering how his “strong man” approach would play out in office. Some are skeptical of his rhetoric, arguing that Trump, if elected, would have to contend with the reality that presidents generally cannot act alone. The Constitution divides most powers between the President and Congress: presidents cannot go to war unilaterally, they cannot make unilateral decisions about most matters involving national security. The constitutional system of separation of powers uses checks and balances to make sure no one branch of government has concentrated power.

That is certainly correct, in theory. In practice, however, recent presidents have shown a willingness and ability to write Congress out of the equation. A President Trump who determined to act without Congress would have recent precedent to draw on—most notoriously, the unitary executive theory relied on by the Bush administration. The unitary executive theory rejects the idea of checks and balances, claiming unchecked power for the president, even the power to set aside criminal laws. As political scientist Jim Pfiffner observes, this theory assigns presidents “powers once asserted by kings.” The Bush administration invoked the unitary executive theory to justify torture and warrantless surveillance prohibited by criminal law, and to claim complete power over decisions to use military force.

It is well worth finding out what Trump—and other candidates, for that matter—think of the unitary executive theory. During the 2008 election, reporter Charlie Savage surveyed the presidential candidates to ask specific questions about the scope and limits of executive power. Of course, getting candidates on the record is not enough—President Obama has not adhered to the limits on power that he acknowledged existed when he answered Savage’s questions as a candidate in 2007. But it is a useful starting point to ask Trump and other candidates whether they acknowledge constitutional limits on presidential power.

Some of Trump’s public statements suggest he believes that constitutional limits would not bind him. For instance, during a debate, Trump said that President Obama lacked the “courage” to use military force against the Assad regime in Syria in 2013. In reality, President Obama lacked constitutional authority to act alone against Syria—he needed congressional authorization, which Trump seemed to dismiss.

Trump has also said that he would order the military to carry out torture, declaring that they would follow his orders, whether lawful or not. Trump seemed to later backtrack when he said he would “stay within the laws” in responding to ISIS—but his new position does not immediately make sense.

Trump said he’d like to change the law to allow waterboarding. But waterboarding is torture. Torture, by definition, is illegal—both under U.S. law and international law. The U.S. has signed a treaty prohibiting torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. Would Trump have the U.S. withdraw from the treaty? If Congress did not support him, would he act anyway?

Candidate Trump has proposed a number of radical, dangerous ideas. He is running a campaign based in large part on the promise that he would be a strong leader who would take actions other presidents have been unwilling or unable to carry out. The U.S. constitutional system has checks in place that, in theory, can set limits on presidential power. But those checks have not functioned well during times of crisis, including in the years since 9/11—especially when Congress is passive or deferential. It’s essential to consider what a President Trump could do to deliver on his promise to rule as a strong leader. The answer is that it could largely depend on how far he is willing to go.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com