In June 1966, a black civil rights worker in Clarke County, Mississippi, met a fresh recruit at the local bus station. He loaded up John Cumbler, a white college student from Wisconsin, and took him for a ride. He drove south toward Shubuta, a small town of seven hundred located at the southern end of the county. Just north of town, John Otis Sumrall turned left onto a dirt road. Pocked with puddles, the route wound past a few clusters of cabins before narrowing into a densely wooded corridor. It seemed a road to nowhere, or at least nowhere one might want to go. A fork in the road revealed the Chickasawhay River, and a rusty bridge.

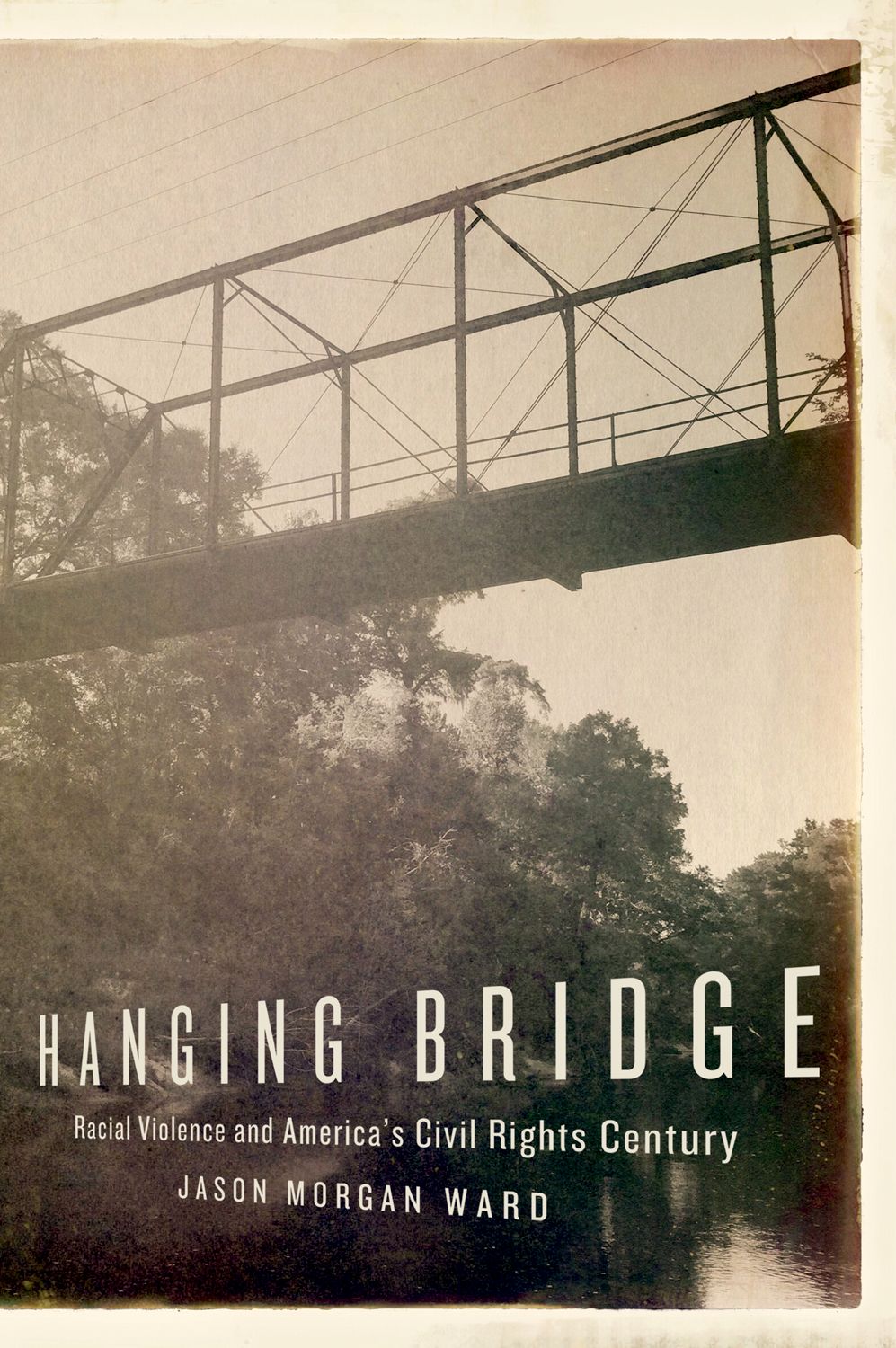

The steel-framed span loomed thirty feet above the muddy water. At the far end of the hundred-foot deck, the forest swallowed up a dirt road that used to lead somewhere. Years of traffic rumbling across the bridge had worn parallel streaks into the deck, and heavy runner boards covered holes in rotted planks. Metal rails sagged in spots. Still, the reddish-brown truss beams on either side stood stiff and straight, and overhead braces cast shadows on the deck below. On that rusty frame, between lines of vertical rivets, someone had painted a skull and crossbones and scribbled: “Danger, This Is You.”

“This,” Sumrall announced to Cumbler, his new recruit, “is where they hang the Negroes.”

“The way he said it,” Cumbler remembered, “it could have happened a hundred years ago, or last week.”

Now closed to traffic, the Hanging Bridge still stands. In 1918, nearly a century ago and just five weeks after Armistice Day, a white mob hanged four young blacks—two brothers and two sisters, both pregnant—from its rails. This was several days after their white boss turned up dead. “People says they went down there to look at the bodies,” a local woman recalled fifty years later, “and they still see those babies wiggling around in the bellies after those mothers was dead.” When the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)—an organization less than ten years old at the time— demanded an investigation, Mississippi governor Theodore Bilbo told them to go to hell.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Twenty-four years later, white vigilantes hanged Ernest Green and Charlie Lang—fourteen and fifteen respectively—after a white girl accused them of attempted rape. Newspapers nationwide ran photographs of the two boys’ corpses and that same river bridge. “Shubuta Bridge’s Toll Stands at Six Lynch Victims,” the Chicago Defender announced. “Some place the figure at eight,” the prominent black newspaper continued, “counting two unborn babies.” In the wake of the latest atrocity, the Defender dispatched a black journalist to the nation’s new lynching capital. In Meridian, a small city forty miles north, the undercover reporter asked a black taxi driver for a ride to Shubuta. “No sir,” the cabbie replied. “I’d just as soon go to hell as to go there.”

Local whites proved just as blunt. A white undercover investigator sent to Clarke County in November 1942 spoke with a local farmer who bragged of his town’s most infamous landmark. “It’s not in use anymore as a bridge,” he boasted. “We just keep it for stringing up [n*****s].” Whites had to “mob” blacks from time to time, he explained, to keep them in line. “We had a case of that here just recently,” he added, “two fourteen-year-old boys….We put four up during the last war.”

From Jim Crow’s heyday to the earliest hints of its demise, the Shubuta bridge cast its shadow on Mississippi’s white supremacist regime and the movement that ultimately overthrew it. In the World War I era, on the heels of a three-decade campaign to disenfranchise and segregate African Americans across the South, vigilantes used brutal violence to deter challenges to white supremacy. A generation later, during World War II, local whites again relied on racial terrorism to prop up an order they claimed was under unprecedented attack. In both of these pivotal moments, national attention and protest politics collided at a lonely river bridge, where the pervasive violence of the twentieth-century South rose sharply and tellingly to the surface.

The bridge boasted a history as gory as any lynching site in America, but its symbolic power outlasted the atrocities that occurred there. While local whites emphasized its usefulness in shoring up white supremacy, civil rights supporters recognized its potential to galvanize protest. After the 1942 lynchings, a black journalist branded the bridge a “monument to ‘Judge Lynch.’” The “rickety old span,” Walter Atkins argued, “is a symbol of the South as much as magnolia blossoms or mint julep colonels.” With its grim history, as well as with the myths and legends it inspired, the bridge reinforced white control and deterred black resistance. The structure was not just a monument but also an “altar” to white supremacy, as the journalist put it, a place “to offer as sacrifices” anyone who threatened that power. The river below the bridge flowed gently, yet Atkins predicted “a long overdue flood that will smash and sweep away Shubuta bridge and all it stands for.”

MORE: New Report Documents 4,000 Lynchings in Jim Crow South

A generation after the 1942 lynchings, that flood finally hit. Civil rights workers, federal agents, and television reporters poured into the state in the mid-1960s, though the rising tide of protests and marches did not reach everywhere. Despite massive demonstrations in nearby places such as Meridian and Hattiesburg, Clarke County seemed left high and dry. Even as local activists and allies across the state challenged segregation and disenfranchisement, the Hanging Bridge still stood as a reminder of Jim Crow’s past and violent potential. Few civil rights workers ever set foot in Clarke County. The Mississippi movement’s high-water mark—1964’s Freedom Summer—came and went with no Freedom Schools and no marches in Shubuta; only a handful of the county’s black residents registered to vote.

Local people had a ready answer for anyone who wondered why the movement seemed to have passed them by. Old-timers across the county still spoke of a bottomless “blue hole” in the snaking Chickasawhay River, where whites had dumped black bodies. Far more mentioned the bridge that spanned the murky water. The myths could be just as muddy, the details dependent on the storyteller. However the events were mythologized, a fundamental truth remained. “Down in Clarke County,” a Meridian movement leader recalled, “they lynched so many blacks.” A white northern journalist who visited in the wake of the 1942 lynchings predicted that the mob impulse would die hard. “The lynching spirit means more than mob law,” he warned. “It means the inability of so many white Southerners to keep their fists, their clubs, or their guns in their pockets when a colored person stands up for his legal rights.”

When black activists in Clarke County defied mobs and memory in pursuit of political power and economic opportunity, they provoked a new round of violent reprisals. In the process, they fixed outside attention on problems that persisted in the wake of the soaring speeches and legislative victories of the civil rights era. In this rural corner of Mississippi previously known for lynchings, those activists used that infamous reputation to focus national attention on ongoing battles against racial terrorism, grinding poverty, and government repression. Their story reaches back into generations when the rural South seemed all but cut off from national campaigns against discrimination and abuse, but grassroots activism in Clarke County also extends the story deep into the 1960s and beyond. Racial violence—both in bursts of savagery that sent tremors far beyond Mississippi’s borders and in the everyday brutalities that sustained and outlived Jim Crow—connects the generations and geographies of America’s civil rights century. In reclaiming these stories, we bridge the gap between ourselves and a past less distant than many care to admit. To acknowledge the role of violence in shaping our racial past is no guarantee that we can face honestly the ways in which it informs our racial present, but it is a place to start. In the history of lynching, place is often difficult to pin down with precision—hanging trees long since felled, killing fields reclaimed by nature, rivers and bayous that hide the dead. Yet one of America’s most evocative and bloodstained lynching sites still spans a muddy river, and it still casts a shadow.

Adapted from Hanging Bridge: Racial Violence and America’s Civil Rights Century by Jason Morgan Ward with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2016 by Oxford University Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com