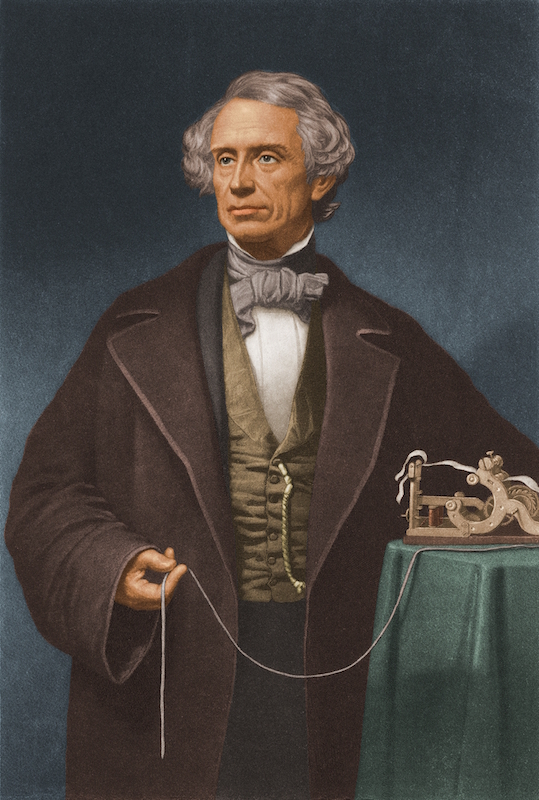

The telegraph has become the epitome of an obsolete technology. The last telegram was sent two years ago, and Morse code blinked out a few years before that. But in terms of influence, Samuel Finley Breese Morse—born on this day, April 27, in 1791—is anything but obsolete.

Described by biographer Carleton Mabee as “the American Leonardo,” Morse was a man of varied talents and diverse interests. Trained as a visual artist, Morse became one of the early republic’s finest painters and an early adopter of daguerreotype photography. Morse was also influential in 19th-century American politics—though his impact in this area was less salutary. A three-time candidate for public office, Morse lent his influence to anti-Catholic and proslavery political movements.

Even if Morse’s reputation were limited to his famous invention, however, he would still deserve more attention than he receives. Antiquated though it seems, the telegraph represented a revolution in communications rivaling both the printing press and Internet. Indeed, thanks to Morse’s invention, communication was, for the first time in history, no longer limited to the speed at which a physical message could pass between locations. So long as they were linked by telegraphic wires, humans were liberated from the tyranny of distance; Samuel F. B. Morse had, in the saying of contemporaries, “obliterated time and space.”

The path to this legacy was an unlikely one. Born shortly after George Washington’s inauguration as president, Morse was the eldest son of Josiah Morse: early America’s leading geographer and the minister of a venerable Congregationalist church in Massachusetts.

Though given the best education possible, Morse initially showed little promise as a student. He did, however, show promise as an artist. To develop this promise, Morse embarked on a costly, multi-year course of artistic study in Europe. Here, he not only blossomed into a promising painter. He also developed a fierce anti-Catholic fervor—which, according to Morse biographer Kenneth Silverman, partly stemmed from a violent run-in with an Italian soldier at a religious event in 1830. Impressive even by the standards of the 19th century American Protestants, Morse’s anti-Catholicism informed his two unsuccessful bids for New York City’s mayor, as the candidate of a short-lived anti-immigrant party, as well as his failed 1854 run for Congress.

Anti-Catholicism was not the only idea Morse acquired as a result of his European excursions. He also developed the idea for the telegraph while returning from the continent. Travelling aboard the ship Sully in 1832, Morse struck up a conversation with fellow passengers regarding the possibility of using electromagnetism as a means of communication. Confident that such a device was theoretically possible, Morse began building a prototype upon arrival in the U.S.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

It would be years before this device reached maturity. In the meantime, Morse tended to his career as artist, winning a number of distinctions, including opportunities to paint famous contemporaries like James Monroe and the Marquis de Lafayette. He also helped introduce Americans to daguerreotype photography and trained the first generation of American photographers—including Matthew Brady, whose photographs of the Civil War continue to define that conflict.

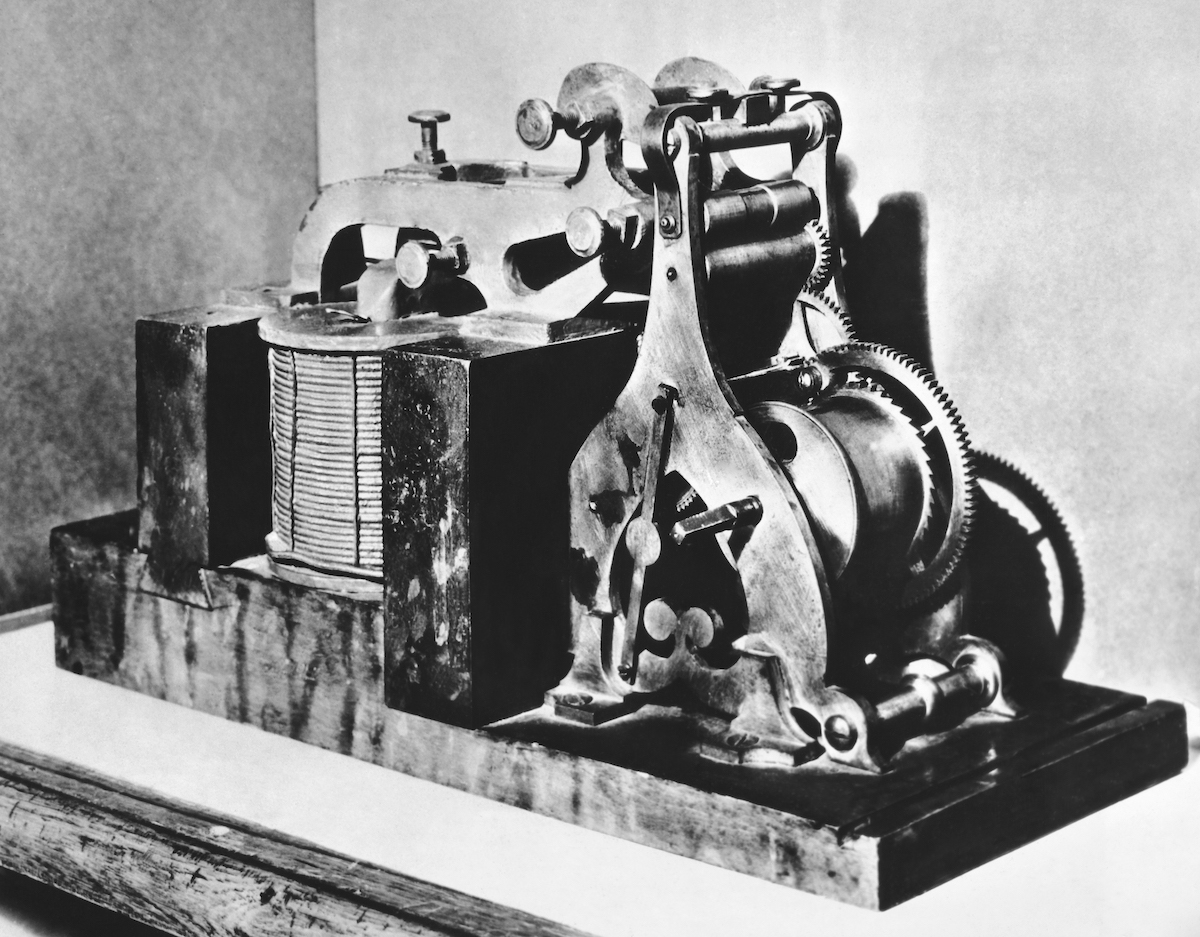

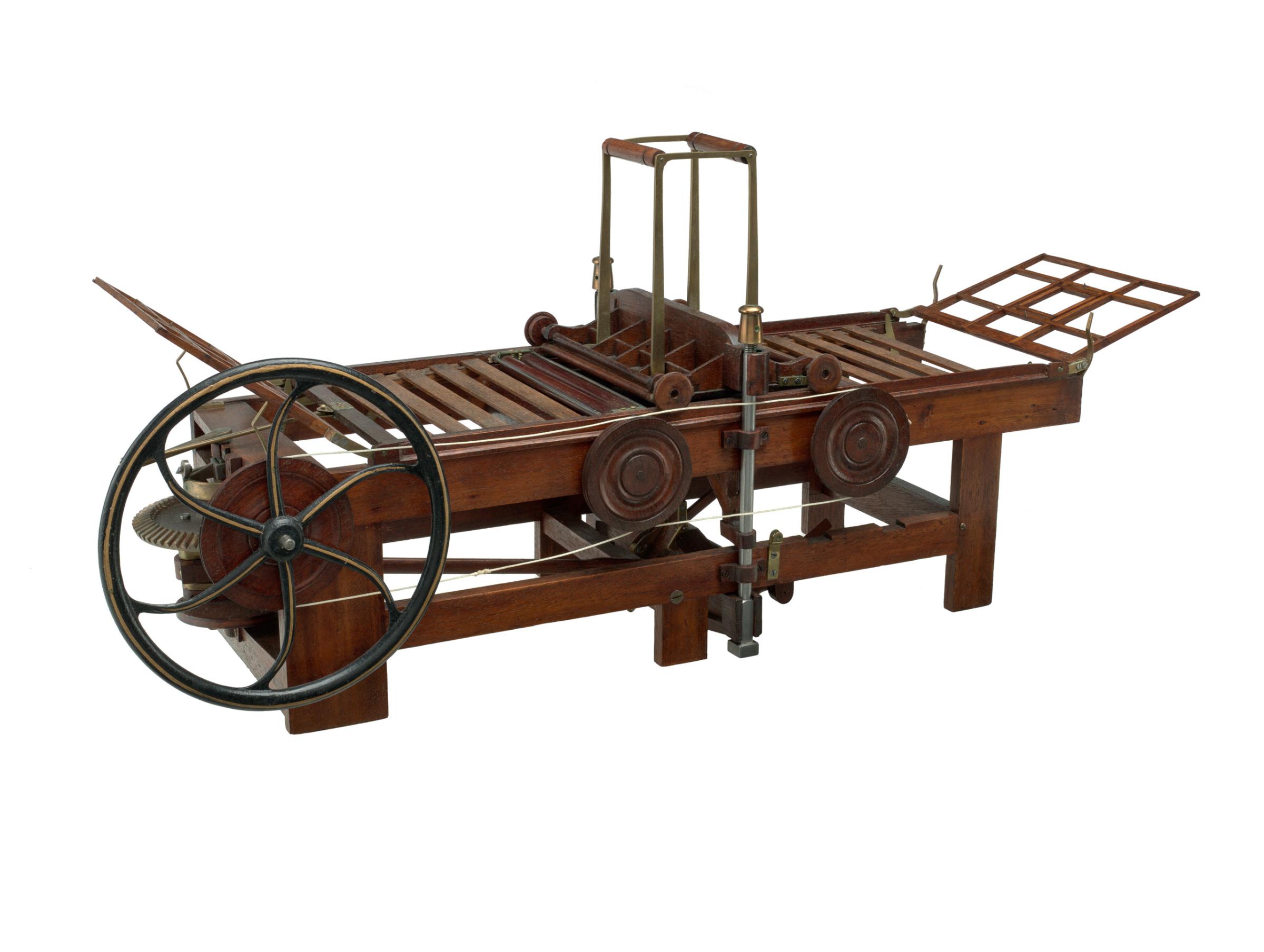

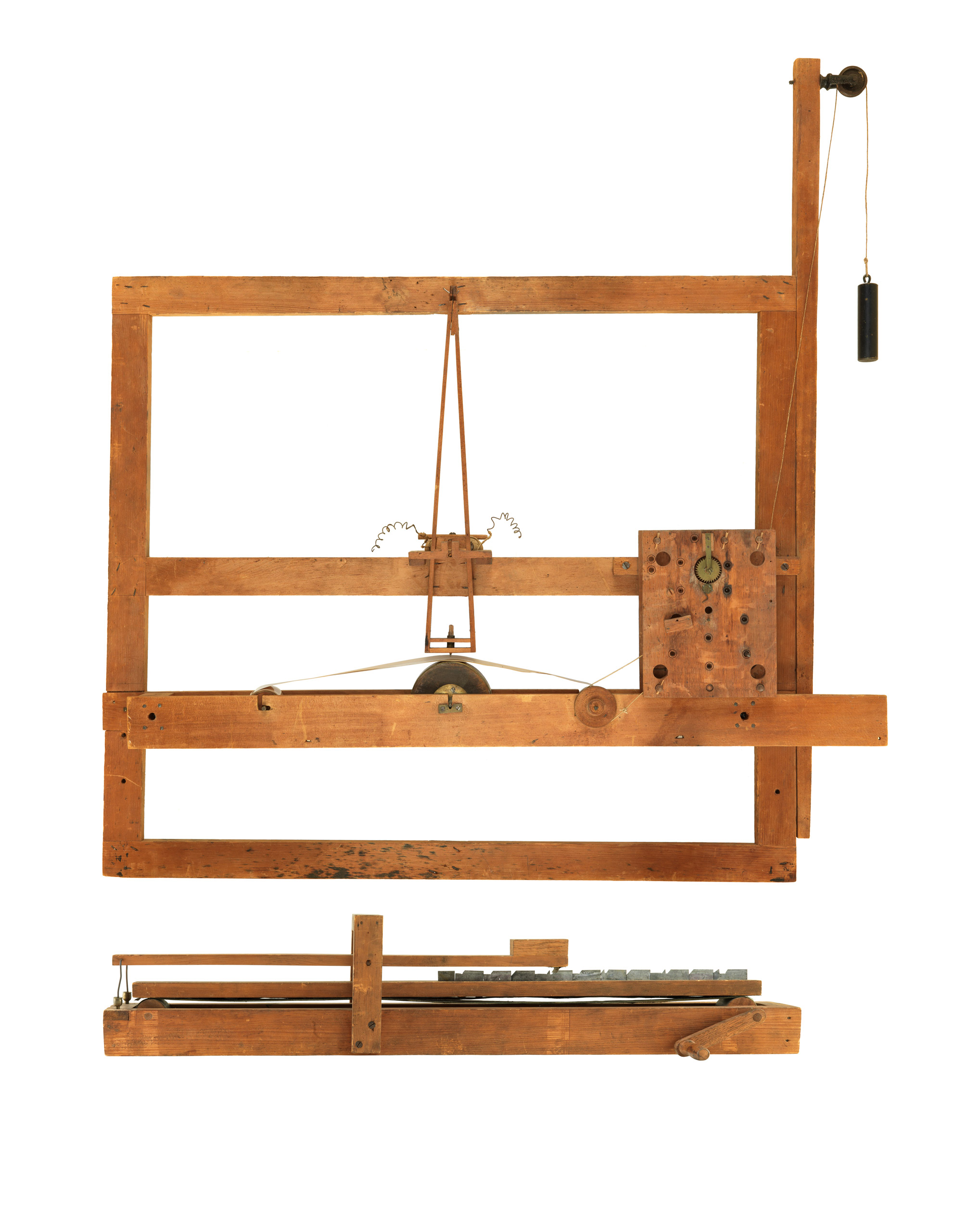

Despite these distinctions, however, Morse was constantly short on cash and thought of himself as an artistic failure. He therefore jumped at the chance to remake himself as a professional inventor. This opportunity arrived in April of 1837, when French tinkerers named Gonon and Serval arrived in the U.S., promoting a new method of long-distance communication. Fearful of being scooped, Morse overcame fears about the crude state of his prototype and submitted the device to public inspection.

The device Morse brought before the public was a far cry from latter-day telegraphs. For example, it lacked the iconic single key that telegraph operators would later use to enter the code that bore his name. But, in other respects, the device approximated the defining features of subsequent telegraphs.

Morse was not the first person to devise the notion of telegraphy—the idea of using electricity to communicate over distances had been circulating in scientific circles since the 18th century and others had already built working devices of less practical design—but he was ultimately the sin qua non of telegraphy. He did more than any other figure, not only to enhance the device technically, but to secure funding for the technology’s early adoption, most notably from Congress. A writer for the New York Times, put it best when he noted the following in 1852:

Grant that MORSE was … indebted to the suggestions of others. … Morse was the man who was publically experimenting, in our midst, on this subject … who besieged the doors of Congress for an appropriation to enable him to demonstrate the practicability of his invention … who, in 1844, laid down the first line of Electric telegraph in this country, from Washington to Baltimore, and sped the first aerial message on its electric path. … If others knew that electricity could be used for recording language at a distance, and kept the knowledge from the public … we think they are too late to claim the credit, after another, by labor and devotion, has accomplished the work.

The Times’ reference to “claiming credit” was not a mere rhetorical flourish. From the time Morse secured Congressional funding for his first telegraphic highway—which carried as its first message in 1844 the Biblical exclamation “What hath God wrought!”—Morse’s life became a three-decade carousel of litigation.

The details of these challenges are too complicated to summarize quickly. Nor are they interesting. Suffice it to say, Morse’s status as inventor of the telegraph was hard won.

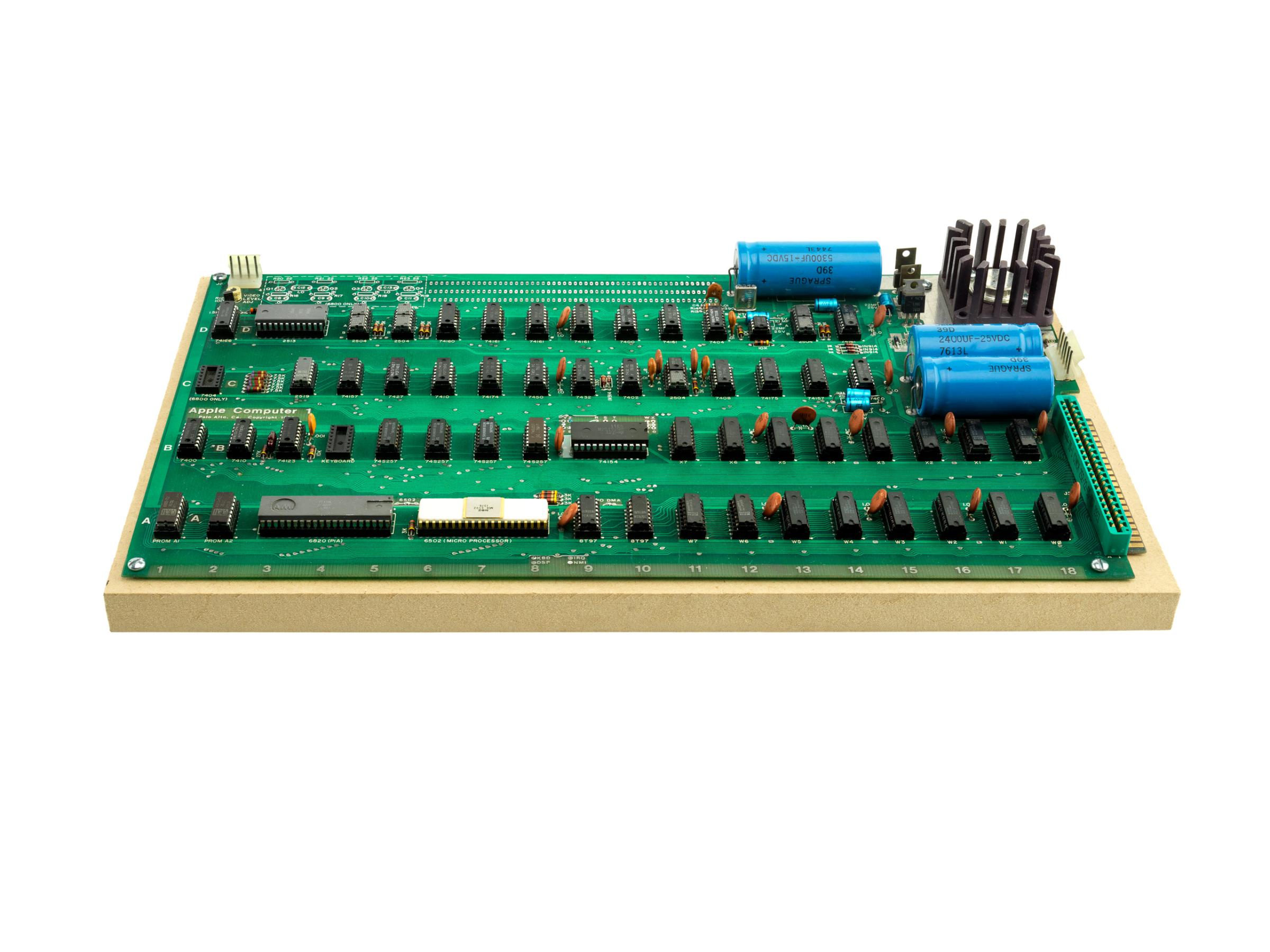

See Original Models of the Apple I and Other Iconic American Inventions

By the time Morse died in 1872, he was a wealthy, celebrated man. His invention, quite literally, reached around the world – with telegraphic cables stretching across Eurasia, the Bering Strait, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean. And Western Union, the largest telegraph operator in the United States, was on its way to becoming one of the greatest corporate behemoths in an age of monopoly. The effects of this telegraphic infrastructure were far reaching. Military leaders flashed orders to distant battlefields. Businesspeople set commodity prices on opposite sides of the globe. And journalists responded to growing demand for timely news updates by forming the Associated Press.

Not all of the telegraph’s impacts were quite so obvious, however. In recent years, scholar Trish Loughran has argued that the telegraph pushed America toward Civil War by forcing readers in the North and South to grapple with profound differences in how they viewed the nation and its future. And historian Garry Wills has argued that the telegraph’s forced brevity revolutionized Abraham Lincoln’s rhetorical style, leading the 16th president toward the famous terseness of the Gettysburg Address.

The brainchild of one of the world’s last great polymath thinkers, telegraphy helped inaugurate the instantaneous, intensively-networked world we inhabit today. As the words of this article are beamed, simultaneously, to the four corners of the world, it seems only fitting to celebrate the life of the telegraph’s brilliant, and brilliantly flawed, inventor.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Sean Trainor has a Ph.D. in History & Women’s Studies from Penn State University. He teaches history and humanities at Santa Fe College and blogs at seantrainor.org.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com