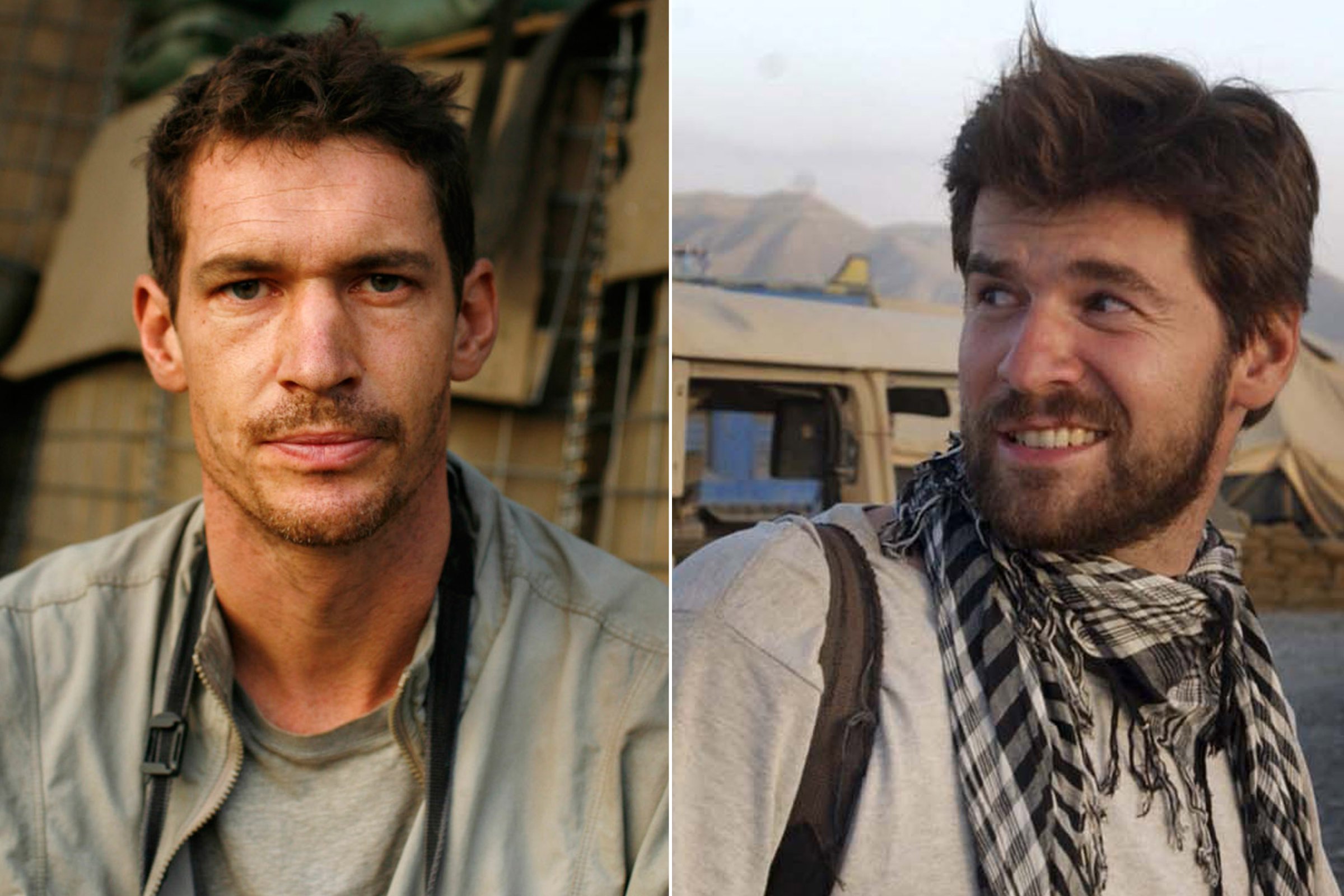

On April 20, 2011, in rebel-held Misrata, Libya, a mortar, targeted at a group of journalists, killed photographers Chris Hondros and Tim Hetherington. Their death deeply affected the close knit community of war photographers and journalists.

On the attack’s fifth anniversary, TIME asked their friends one question: what did you learn from Hondros and Hetherington?

Chris Hondros (1970 – 2011)

Christina Piaia, board president of the Chris Hondros Fund and public interest attorney on human rights policy

I remember walking down an uneven cobble stone street two nights before April 20, 2011. Thoughts sped through my mind all day, yet during this evening walk my thoughts slowed as feelings of gratitude and joy came upon me. I felt a sense of immeasurable happiness- I felt so much love for Chris and our love appeared in such a sweet, organic way. But, this greater sense of gratitude is the feeling that overwhelmed me. I began to think of a conversation Chris and I had the evening after he returned from a grueling assignment to Afghanistan in October, 2010 where his colleague and friend Joao Silva had been gravely wounded.

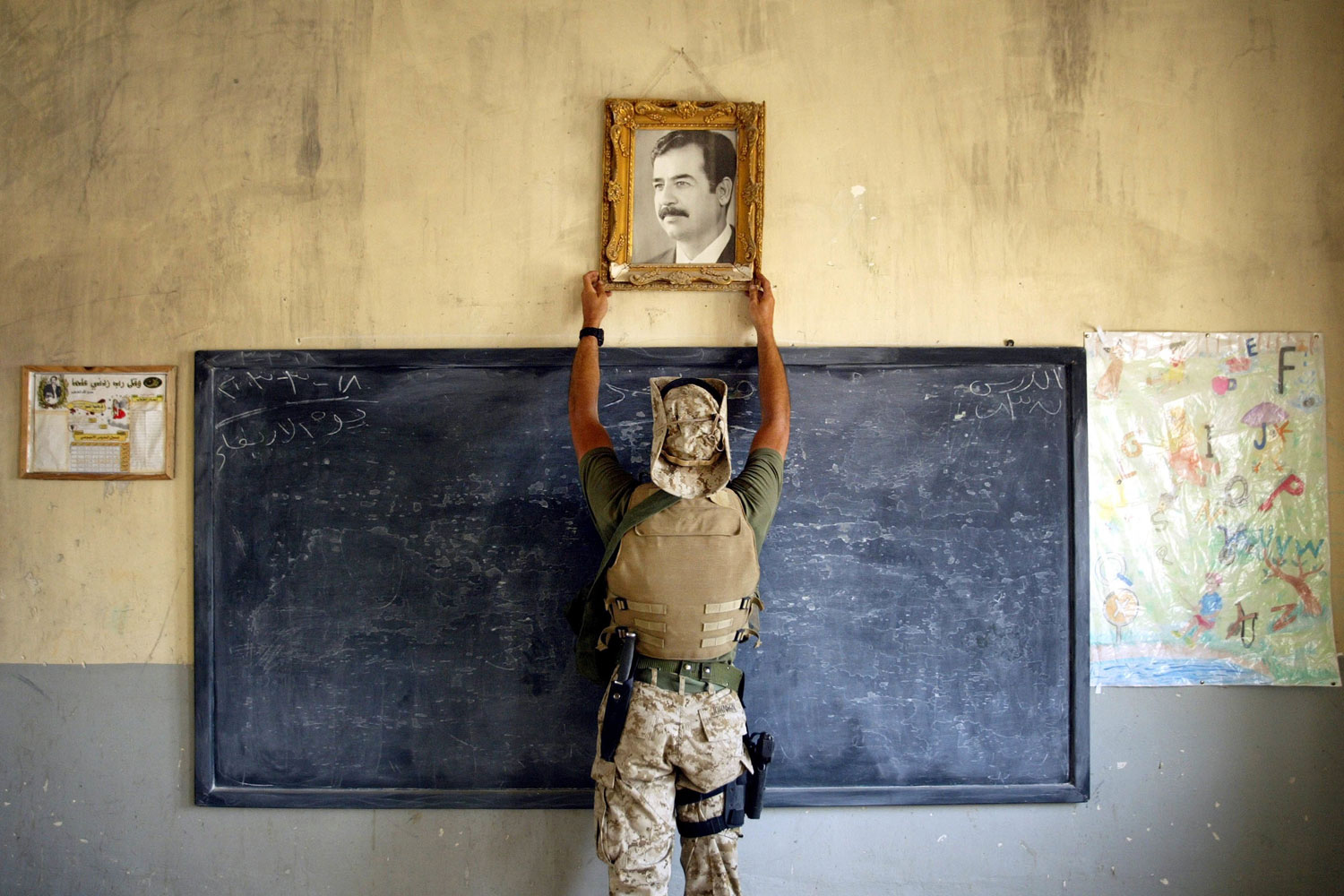

That night, Chris described many things to me: the schoolyard in Liberia exactly before and after a horrible attack that left the schoolyard, full of young children, dead; masses upon masses of bodies days after the earthquake tragically hit Haiti; and a conversation that he had with a young soldier about his buddy who stepped on an IED and blew off both his legs and an arm. Chris wondered in an email he wrote to me “Can you imagine? What a trip that must be [referring to the soldier’s wife traveling to the army hospital in Germany]. What’s the dominant feeling? Relief that your husband is still alive? Fear about the future and new reality? Anger…? All of that, I guess. It does make me appreciate life much more, and make me want to live it more fully, more completely…”

As Chris delicately described these scenes, he always returned to this concept: life is dangerously fragile. How cliché it may seem, he remarked, one second we are here and the next second we are not. As he described what he saw and how he felt and smelt death so close his experiences created a discerning and honest insight into life’s fragile state. This insight resonated so strongly in my heart and mind as he unknowingly shared these thoughts so intimately with me – it seemed as far from cliché as ever to me, especially after April 20, 2011.

Chris showed this fragile insight to all of us in his beautiful images and soulful vision. For me, the lesson and wisdom he gracefully and humbly shared became the most beautiful and important gift I could have ever imagined. It is present in every part of the life I live – both for the long run and in the hours of every day too. To have a true sense of gratitude for the life we live is a lesson I learn from Chris as each day passes.

Andrea Bruce, photojournalist and recipient of the first Chris Hondros Fund Award

Chris read Tolstoy while on assignment. He listened to classical music. Only classical music. He owned his individual-ness within our community, embraced it, diving into the creative process head first—teaching me to be myself, ignore the expectations others place on me, and search for other sources of inspiration that can refresh our vision.

And he always had my back, demonstrating that the true sign of being an accomplished photographer was being supportive to others, especially in the field. Since meeting Chris, I feel I can spot the pros… those that take the time to help others.

Todd Heisler, staff photographer for the New York Times

Chris never lost his cool. Well, I’m sure he did, but he rarely showed it. I always marveled at how calm and collected he always seemed. Cavalier, even. He’d love that.

You’d think I’d have some amazing war story to reflect this but I don’t. Though we met in Baghdad at the end of 2003, we never really worked in a war zone together. But even at the breakfast table at the Hamra, he had an air about him that seemed to put everyone at ease. He had this marvelous ability to digest information in such a rational way that made you feel like everything was going to be ok. He always saw the big picture. “You’ll be fine” was a common refrain heard from him, whether he was doling out advice about an upcoming embed or you were considering a career move. It was like a mantra.

Oddly one memory that stands out is of driving through Manhattan with him. It was a typical New York commute, filled with blaring horns, criss-crossing cab drivers, careless pedestrians and daredevil bike messengers. But classical music filled the inside of Chris’s car and he drove along steadily, pontificating about this and that as if we were chatting in a quiet corner in one of his favorite coffee shops. All that chaos around us and he never got pulled into the madness.

Chris Hondros in Memoriam

Pancho Bernasconi, vice president for editorial at Getty Images

It is difficult to put into words the one thing I learned from Chris as I have yet to fully recognize all I absorbed from him. The things you learn from friends and colleagues reveal themselves at different points in your life and that was and is very much the case for me with Chris.

In reflecting on our professional and personal relationship, I’m struck most by Chris’s ability to be present and in the moment. It’s what made him such a profoundly talented photographer but it’s what also made him such dear and important friend to so many of us. It is a lesson that is still seeping its way into me and I am grateful to have been shown its power by such a good and decent man.

Tim Hetherington (1970 – 2011)

Idil Ibrahim, director and writer

Tim and I had many things in common. We shared a passion for human connection, for powerful storytelling and for the importance of using our creativity to shed light on critical social issues. But he also taught me an incredible amount about myself, and about the world. My lessons from him are endless.

After losing him I found myself searching for solace and comfort to fill the void, things I then found in the places I traveled and the beautiful and inspiring people I have met since. I operate in the world with less boundaries now and live with a greater sense of purpose and adventure. I’ve inherited Tim’s zest for life and a sense of openness that has only enhanced the connections I make with everyone I meet.

In his absence, I feel him with me as I move forward. I see him in the photos I take, the films I write, the exhibitions I attend, the framing of my shots. He is with me on my adventures, whether I am interviewing pirates marooned in Kenyan prisons, swimming in the deep sea, sharing laughter in a refugee camp, trudging through swamps in south-western Uganda, or watching the sun dip below the horizon off the coast of Beirut. I try to live without limits: honest, relentless and deeply committed to leaving this world better than I found it. I thank Tim for that.

Stephen Mayes, director of the Tim Hetherington Trust

After 15 years of feeling my way through the world with Tim as my thought-partner I can’t point at any one thing that I learned from him. He was just part of my process. By the time he died I couldn’t distinguish which of our ideas about photography and the media had originated with him or me, they just bounced between us accreting wisdom in layers as we went along.

Five years on, I have so many incomplete thoughts that I’d love to develop with Tim. Top of mind today is Tim’s self definition as a “visual storyteller.” He certainly had moments as a visual storyteller but he was in the process of unpacking his education in English and Classics and applying everything he had learned from Homer, James Joyce and others. More than simply telling stories he was exploring what it meant to tell stories. How can I complete this thought without Tim’s insight?

Max Houghton, senior Lecturer in Photography at the London College of Communication and a former editor of Foto8

Tim was an essential part of the organization Foto8, where Lauren Heinz and I first met him, with Jon Levy, in a cramped office above Great Portland Street. Tim treated everyone as an equal and when he talked with people, he would be listening all the time and learning from them. His first commitment was to the people in the stories he told; the subsequent publication of such stories was vital, but only in relation to dissemination of knowledge. He also placed the idea in my head of looking all the way around a potential photographic subject, as one would a classical sculpture. In his filmic work ‘Diary‘, he elucidated the question of “where to locate the self” as a documentary photographer with particular – and customary – grace.

James Brabazon, documentary filmmaker and producer of Which Way Is The Frontline From Here? The Life and Time of Tim Hetherington

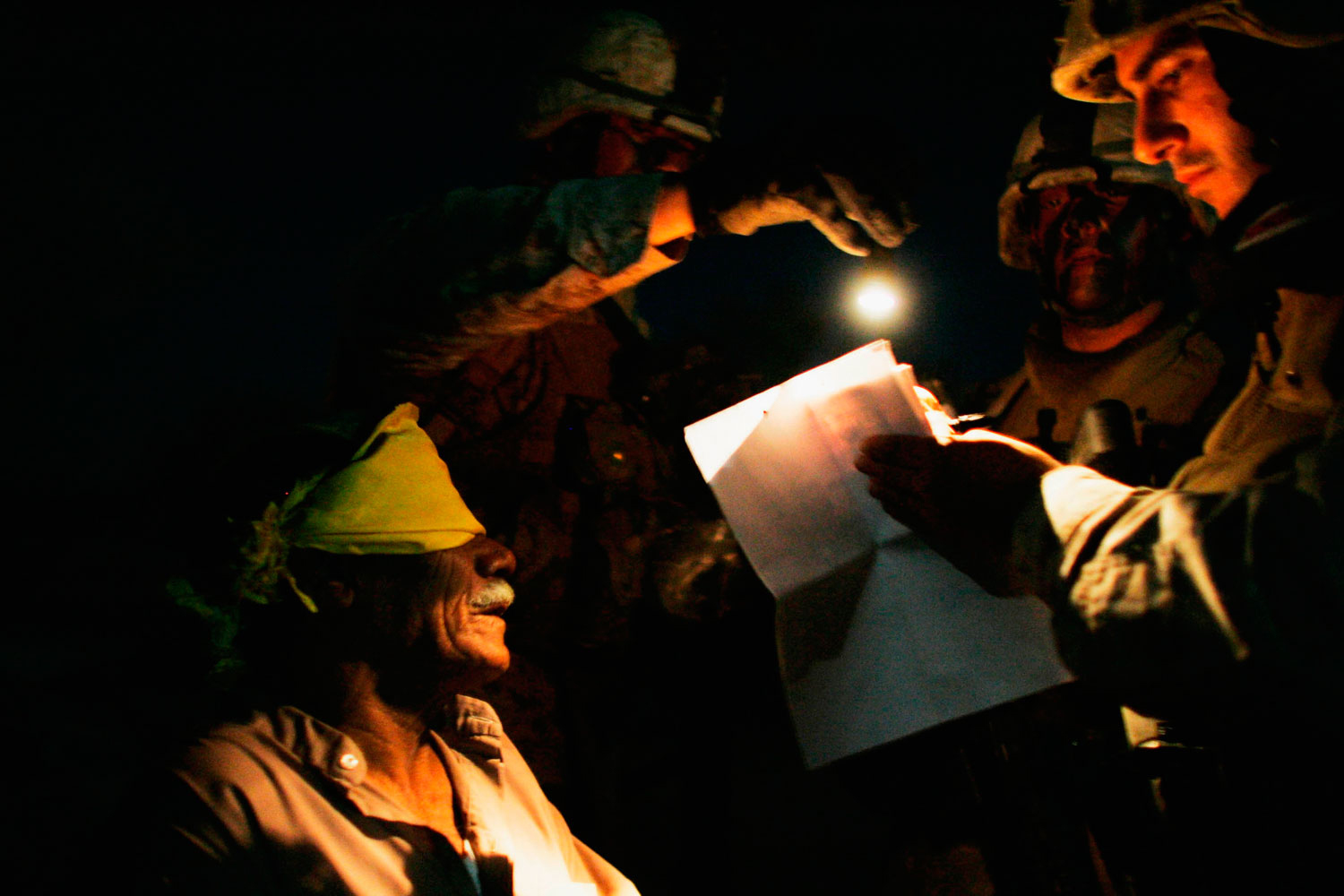

I learned from Tim to look through the lens, not at it. I learned to be serious in my work, but not to identify with the medium; that the medium is less important than the message; and that the message is inseparable from the messenger. I learned that without curiosity there can be no message, no image, no truth. I learned that beauty is not inferior to truth; and that truth is not tempered by beauty. I learned from Tim what war means: that time is finite and loss is absolute; but that the clocks restart and there will be a new day at dawn.

Art Blundell, partner at Natural Capital Advisors

What did I learn from Tim? Empathy…

More than anyone I’ve met, Tim was engaging. His genius began with curiosity: he was interested in connecting with you (and everything around him). He drew you in and made you more interested. He looked for the “special” thing about you, and that inspired you to look at the people around you with new eyes. That conversation extended into his story-telling. After his driver in Yemen told him he was unsure about the existence of heaven but swore the existence of extraterrestrials, Tim saw gas stations differently. Lit up at night they became “space stations” in the desert…

He was drawn to exploration and revolution: he took his middle name from the Odyssey; he loved Christopher Marlowe’s story-telling; and he studied Ulysses… Standing on the shoulders of these transformers, he was looking for new ways to tell our stories. He saw his last documentaries as searching for the answer to our most tragic paradox: why do we—as civilized people—continue to kill? Liberia was about “other” killing “other”; Restrepo: “us” killing “other”; his third was to be about “us” killing “us”. He felt the answer held within the triptych was that young men are used to kill so that old men can get what they want. As simple and as profound as that…

Tim saw the war photographer as Dr. Faust, making a deal with the devil not just to understand this essential question about our basic humanity, but gaining immortality to allow him to travel to dangerous war zones. But with every image taken, it is the photographer whose soul is tortured.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com