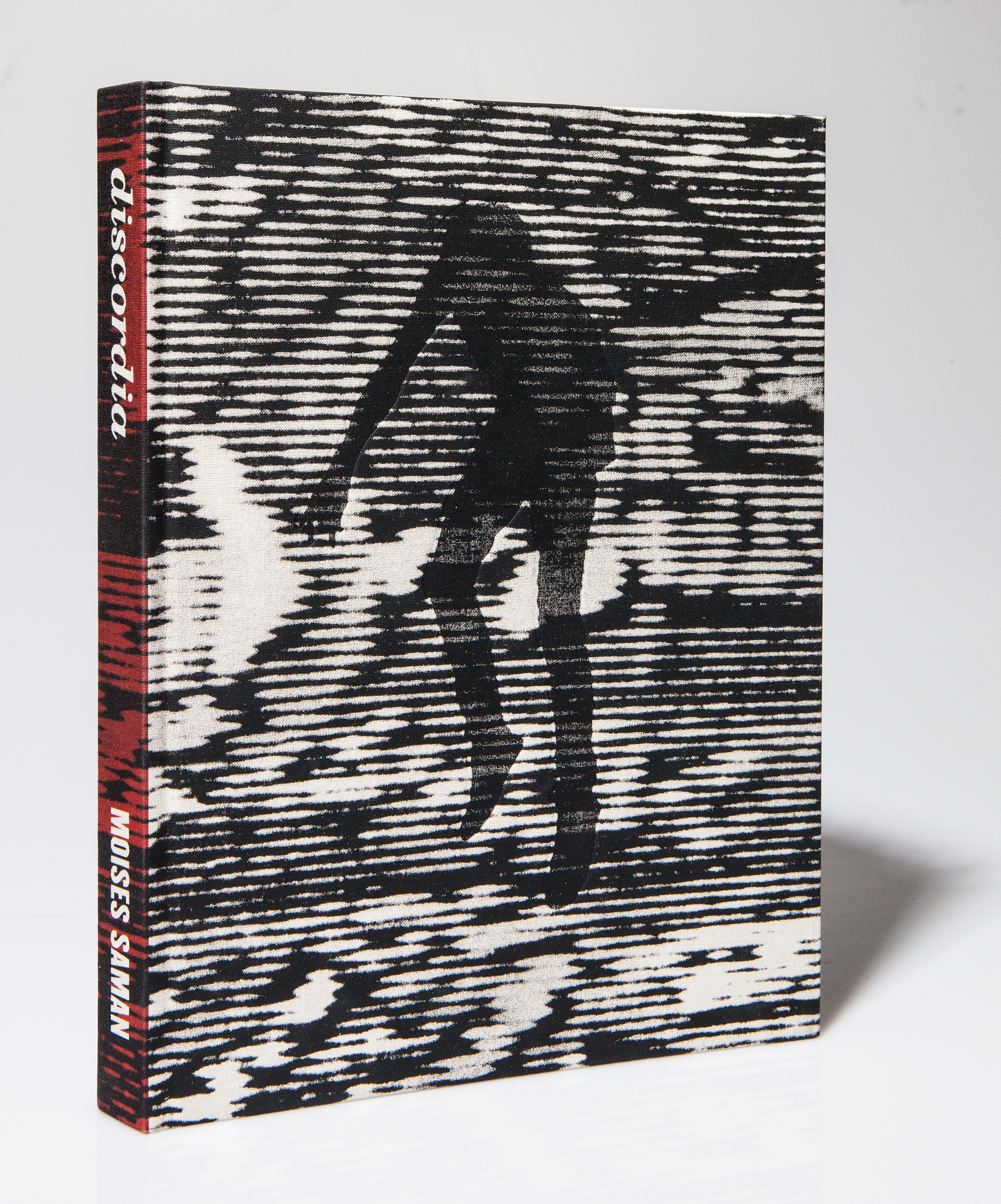

What started as a series of assignments across a Middle East in the throes of popular uprisings quickly became, for Magnum photographer Moises Saman, a personal journey that’s culminated into Discordia, a self-published book that looks at five years of the Arab Spring. Through 127 photographs, Saman creates a new sort of narrative that combines “the multitude of voices, emotions, and the lasting uncertainty I felt,” he says, as he worked in Tunisia, Egypt, Iraq and Syria.

He speaks to TIME LightBox about the creative process behind Discordia.

Olivier Laurent: When you were reporting on the Arab Spring over the last five years, how did the idea of Discordia come about?

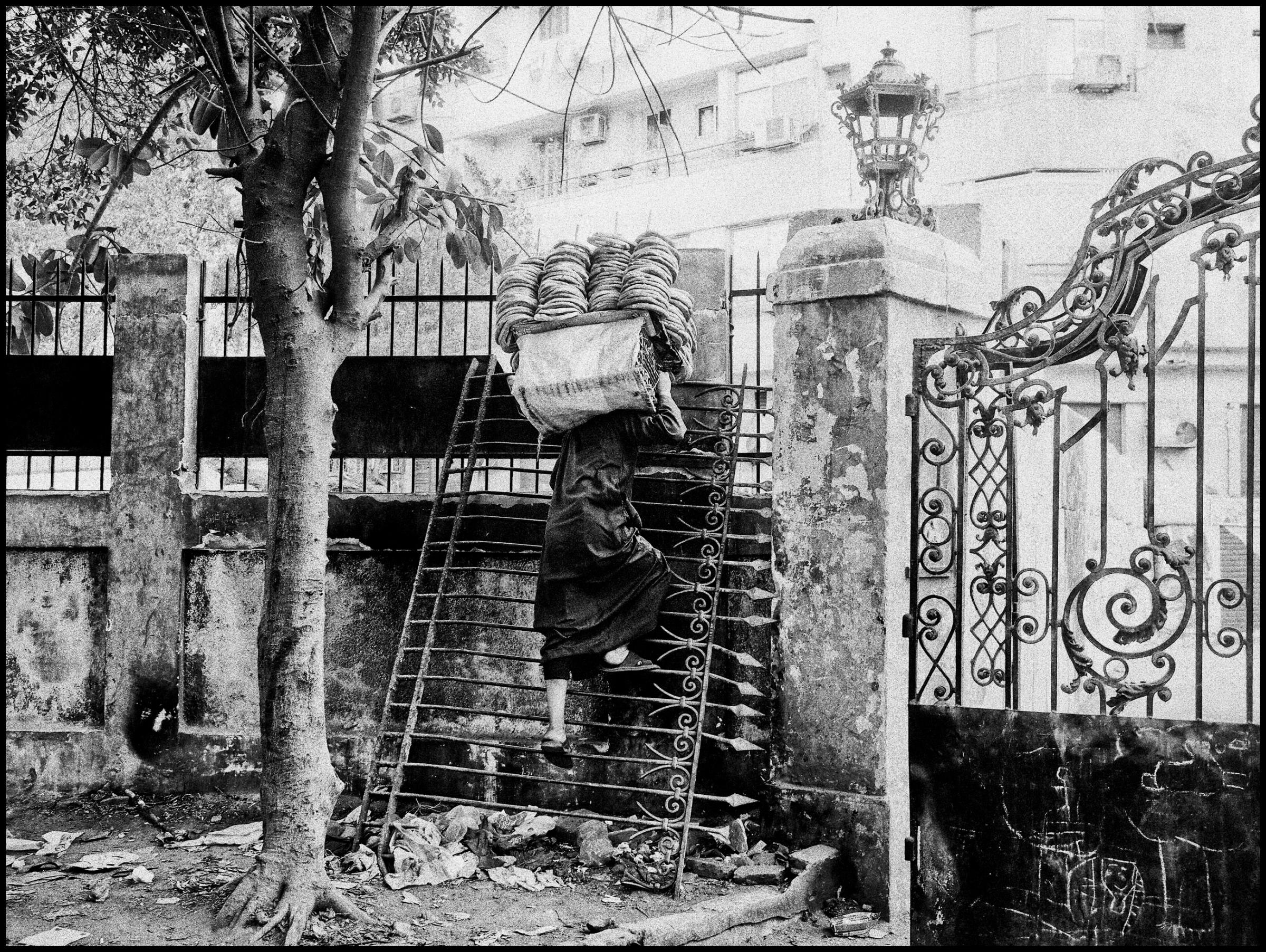

Moises Saman: The idea for the book came from my desire to make sense of the confusion and uncertainty that ultimately defined my time living and working in the region. In the course of these past few years the many revolutions overlapped, and in my mind became one blur, one story in itself. In order to find some introspection, I chose to loosen my approach as a photojournalist by shifting the focus from the “news” aspect of the story to a more ambiguous visual narrative, one that was more in tune with my own experience witnessing the blurring of the lines between victim and perpetrator.

Olivier Laurent: How do you begin to think about the images you want to include?

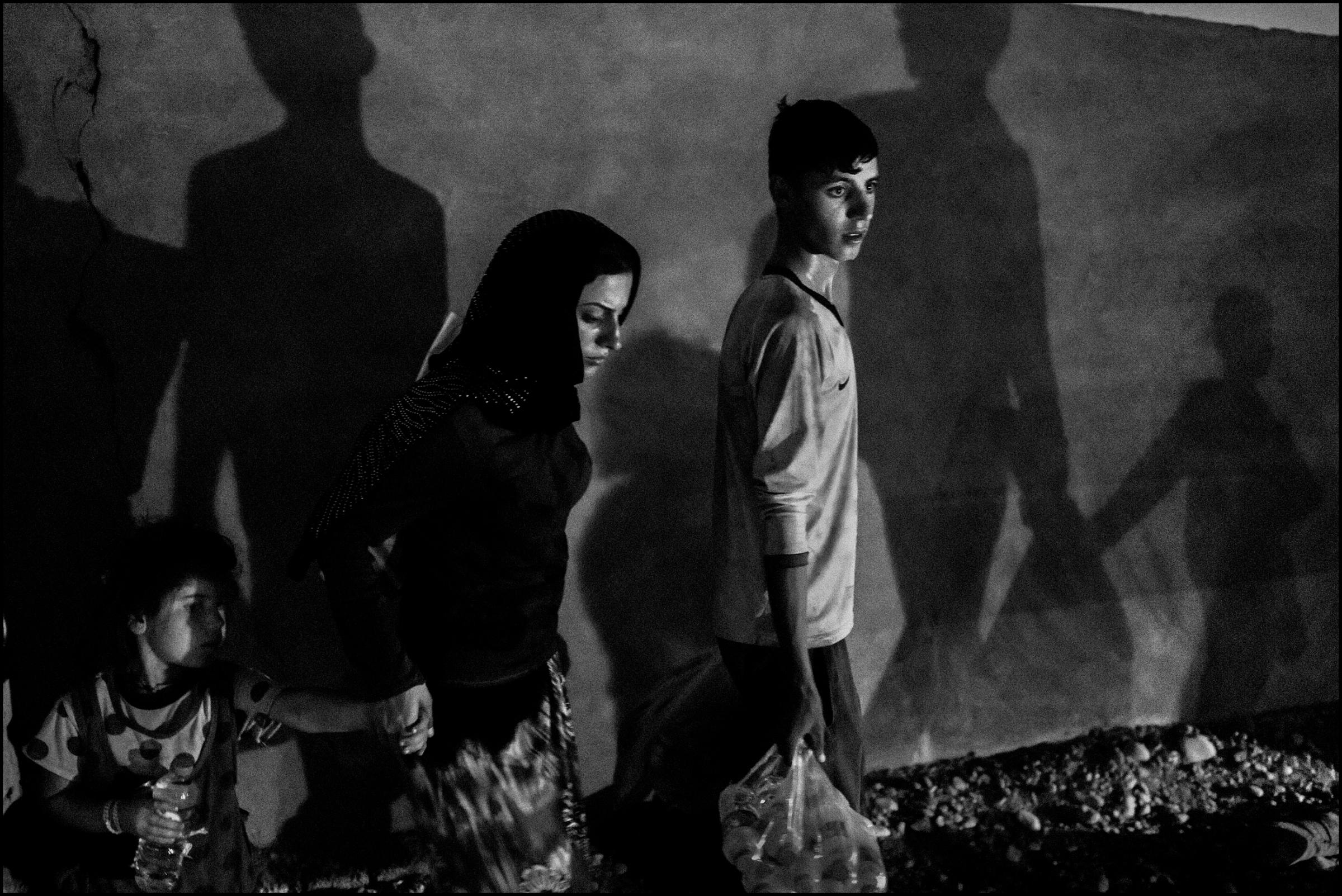

Moises Saman: I collaborated with my friend Daria Birang, a Dutch-Iranian artist, and together, over a period of at least a year, we went through thousands upon thousands of images stored on my hard drives. Initially we were drawn to the more ambiguous images, devoid of apparent news value, but with certain elements of tension, drama, humor, absurdity, that allow the viewer a greater engagement by sparking their curiosity. The sequence of images was meticulously organized, like in a puzzle, where each single part is bound to the next to create a larger [narrative]. To tell the story the way I lived it, I felt the need to go beyond a particular event or location and play with picture pairings that reflected a shared experience, or the lack thereof.

Olivier Laurent: You talk about pairing images together, and in the book we see, several times, that you chose to include very similar images of the same place and the same events shot seconds or minutes apart from each other. It’s an unusual approach. Most photographers would look to publish only the best photograph from that moment. What was your thinking behind it? How are you using these pairings to drive your narrative?

Moises Saman: It is a creative decision that helps me reinforce a particular element within the larger narrative of the book. For example, in the series of the Syrian mother encountering the body of her dead son for the first time, the idea is to pay due respect to the hopelessness of the situation, by letting it unfold over the course of four pages in four slightly different photographs, forcing the viewer to stay in the moment, page after page, experiencing the various stages of sorrow that transpire in the same dramatic scene. The objective of this particular repetition is to form a bond with the subject that otherwise would be lost in the single “best” image.

Olivier Laurent: Going back to the blurring of the Arab Spring revolutions and how this became one single narrative for you, did this have an impact on how you covered the news? Did your vision or approach shift over these past five years?

Moises Saman: Not at first, the pace was too hectic, and the reactive nature of covering the news on assignment did not allow for much introspection. However, with time it became evident to me that, at a visual level, the facts alone did not grasp the complexity and implications of this historic transformation. During my five-year engagement with the region it became impossible not to question the simple narratives of good vs evil, after seeing first hand how easily the roles of victim and perpetrator can change. It was precisely in this shifting landscape where i found my focus, and where I was able to project my own questions and insecurities.

Olivier Laurent: Did you approach traditional book publishers with this book?

Moises Saman: By the time I started approaching publishers I had a dummy that I felt was final, or pretty close to the book I wanted to make. Throughout the process I was in advanced conversations with a couple of publishers, but we always reached a point where compromises had to be made, in terms of the format, the cover, what type of paper to print on, and where to print the book. In the end I decided that I did not want to compromise, in order to have full control over the end product.

Olivier Laurent: Who did you work with to edit this? What kind of collaboration were you looking for?

Moises Saman: I collaborated with my friend, Daria. She is an integral part of the final editing and sequencing of the book. Her background as an artist was particularly helpful when we were putting together the non-linear narrative that sometimes went against my immediate and straight-forward journalistic instinct. Daria also created the collages in the book, which emerged from our dissatisfaction in portraying the protesters simply as the subjects of an action image, instead we became obsessed with their body language, the theatrics, and performance-like rituals that I saw repeated during the countless demonstrations and clashes that I photographed.

Olivier Laurent: You self-published this book. Which means that you have to act as author, designer, publisher, marketer, distributor. Was this a daunting task?

Moises Saman: I had some help with the design, and I am working a couple of assistants that help me with the distribution in the United States and in Europe, but yes, self-publishing can be an overwhelming endeavor. I find that the hardest part is marketing the book, although I am grateful for the kind reviews that the book has had so far, which helps in ultimately selling the book.

Discordia by Moises Saman is available now.

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com