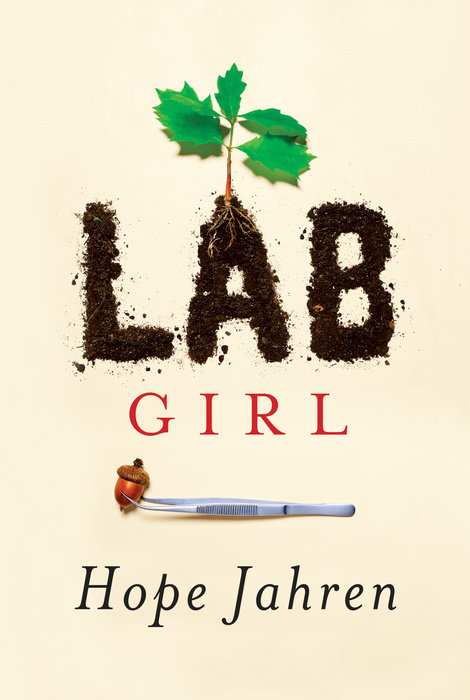

Hope Jahren is the rare breed of scientist who is both an accomplished geobiologist—she’s won three Fulbrights and has built as many labs in as many states—and a fantastic writer. In her engrossing new memoir, Lab Girl, Jahren is alternately funny and moving, whether she’s writing about deciduous trees, her marriage, her lab partner or her childhood. Now a tenured professor with a lab at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Jahren is the author of more than 70 scientific studies and is an outspoken critic of sexism in science. TIME spoke with her recently on those topics and more.

TIME: You study plants for a living. Do you have a lot of them at home?

Hope Jahren: No. Absolutely not. My mom always said: “I’m not going to nurse any old houseplant. If it wants to make it in the world, it’s got to do it on its own.” I like weeds and hardy plants. I don’t have a spiritual talk-to-the-plants thing.

In what ways are plants like people?

They’re also on planet Earth. That’s it. I like plants because they can do things we can’t. They can stand out in the rain and cold that would make us miserable or even kill us, but they adapt.

Do you worry about climate change?

We have, what, 7 billion people on the planet? As an environmental scientist, I think our first need is to feed and shelter and nurture. That has always required the exploitation of plant life and it always will. You can imagine how this plays, but we have to resist the temptation to simplify our environmental messages. It’s not a choice between decimation and preservation. The reality lies in the uncomfortable middle. We can’t assume that’s the only thing the public can absorb.

Your book is a wonderful mix of science writing and memoir. How did it come about?

For years I planned to write a text book because that’s what you do. You get the PhD and publish papers and then you write the book that changes the way people learn something. I sat down to do it and I couldn’t separate my home stuff from my science. It was very frustrating. So I finally just wrote it out and I can’t tell where one stops and the other starts. It’s not quite a memoir and it’s not quite a text book.

Your recent New York Times op-ed about sexual harassment in science caused quite a stir. That’s something you have written about on your blog. Why write it now?

There are things that all scientists know are the reality in science, and the longer I am in this business it was driving me absolutely crazy not to say something. It’s not enough for me to be frustrated. It’s time to talk about it. I have learned that nothing gets readers so fired up as saying something everyone knows is true. My next piece will be called “Water Is Wet.”

Is it hard for you to expose that in a field you love so much?

My challenge is to show that there are these problems, while ferociously defending all that is beautiful and noble about doing science with your hands. My story is not tragic. I have been generously rewarded for everything I’ve ever tried to do. I’m actually a happy ending.

Is discrimination or harassment something you continue to experience now?

Oh yeah. But it’s not special to science. These are expressions of culturally learned power imbalances. We have subscribed to the fantasy that science is or should be free of that.

Why didn’t you write about that much in your book?

Because what I get out of science has very little to do with the professional limits placed on me because I’m a woman. All these instances of discrimination—it’s not that they don’t matter, but it’s that when I think about my career, they’re not close to my heart. Instead, I go to great length to describe in real detail the people who do matter.

People like Bill, your lab partner and best friend. [Ed note: Bill is central to her memoir. Jahren has hired him at her three labs and they’ve done research together around the world.] Do you get asked about that relationship a lot?

No, is the answer to your question. My life is pretty small. Even as a successful scientist, I’m not a public figure. I like people, I just don’t know that many!

In the book, you write about how, when you were pregnant, you lost your lab at Johns Hopkins. What happened?

I ran out of money. It’s always been hard to fund Bill, and that’s non-negotiable for me. I wrote about it because I wanted to show how precarious that is. People don’t know you can have someone so talented and dedicated and be one step away from living on the street. It wasn’t my job that was insecure, it was Bill’s, and I never saw those as separate.

What happens in August when your lab at the University of Hawaii at Manoa runs out of funding?

August is a long time from now. But it’s all or nothing: If there’s not a job for Bill there’s no job for me. We moved to Hawaii because we had a very firm and stable offer with funding for Bill. It’s all or nothing. That’s OK. There is no problem that some combination of work and love can’t solve.

Do you still spend most nights in the lab?

It’s a weird question because we work really hard, but we only do things we want to do. So it’s hard to answer that. I juggle family. If Bill and I go to Costco and get aluminum foil for the lab and food for my fridge and go to Radio Shack and then we go to a movie, is that work? We might have designed an experiment on a napkin, does that count?

So you’re saying it’s not really work, it’s life.

Yes.

You say at one point in the book that if you were going to continue to do science every day, you wouldn’t be like any other woman you know. Did you never have female role models in science?

Not that I can remember. I had women in my life that I looked up to and they were successful and happy and they accomplished different things. I remember thinking ‘I am a scientist and if I spend my life in a lab, I will never get to have those things.’ That felt like a loss. I am also fiercely proud of the fact that science is practiced in the home. It’s how you cook or measure fabric for curtains. My mother was as much of a scientist as my father [who taught science at a community college] but she didn’t have the same chances. So I never did think of myself not as a scientist. The funny thing is, that’s been great for my work. I don’t work in order to prove myself to an institution. So I have to think ‘Why am I doing this?’ ‘What am I getting out of this?’ The system of awards that you’re supposed to chase, I never presumed those were open to me. So the only thing I wanted was one more day in the lab. And it’s still all I want.

What do you wish 11-year-old Hope knew?

You should learn how to reward yourself. Even if you’re really great at this, those external rewards may not come, or they may come but they won’t be as sweet at the rewards you give yourself every day.

You’re very active on Twitter—

I came late to Twitter. It can be a challenge to be the real me and the science me. Believe it or not, I’m actually a really funny person! Twitter has been fun because you can show that side of yourself.

Can you tell me about the time you hijacked Seventeen Magazine’s #ManicureMondays?

People tweet their nails! I had no idea people tweeted their nails. So I poke my head up to say, All these hands are capable of doing all kinds of things, and I tweet my unmanicured hands holding a vial in my lab with #ManicureMonday and #Science. It sort of took off after that. But I wasn’t saying, ‘Hey, look at my important hands.’ I was saying, ‘Those are pretty, but I would personally rather have mine covered in mud.’ Eventually there there were beautiful nails in the mud, and that was just great. When you’re growing up you would look at Seventeen and think: This is what girls are supposed to be. And now, thanks to Twitter, I can join the conversation.

Do you have a lot of trolls online?

I get hate mail, rape stuff. It’s one of the struggles of our age, and I try to be philosophical about it, but I also want to be truthful about the harm.

In the book, you write for the first time about episodes of mania and bipolar disorder. Was that scary?

I cried when I wrote it but it wasn’t scary. You know, we don’t need a book that just sort of talks about things. You have to be real. I also wanted to get through that it’s a real physiological thing. It’s an illness with treatments and medication. I hadn’t seen anyone write it like that before, and I thought it also might help people understand that it’s a real thing. It may be chemicals in my brain but it doesn’t change just how real the experiences were for me.

And that when you get well it’s a weird thing. You know when you’re in love and you don’t need to eat and sleep? But then someone tells you you were sick, and that’s why you were feeling that way. That it is an illness. But for you, it’s still very real.

Siobhan O’Connor is Health Director at TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com