Saying goodbye to an old friend can feel so definitive. Instead, Magnum photographer Patrick Zachmann chose to leave it more open ended. After spending more than 30 years and over 25 self-financed trips visiting China, Zachmann is publishing a 583-page-long book of photographs and journal entries titled So Long, China.

Published by Éditions Xavier Barral, the title is not only a form of farewell but also a reference to the length of time the French photographer spent working in China. This dedication and commitment informs and elevates his work, allowing him to dig below the visible layers of society. “What I like in photography is not just to get some good pictures,” says Zachmann. “It’s to tell stories through sequences and to get as close as possible to the people, to get into an intimacy.”

It’s the reason why after his first trip to China in 1982, he vowed never to return again. Inspired by his early mentor, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and beautiful Shanghai films of the 1930s like The Boulevard of Angels by Yuan Muzhi, Zachmann traveled to China with a journalist’s visa to photograph the film industry. His guide and interpreter gave him minimal access to actors and directors. When the crews all ate meals together in large dining halls, Zachmann had to eat in the corner, separated by a curtain. He felt completely manipulated and the experience became a distinct theme as he continued his China project.

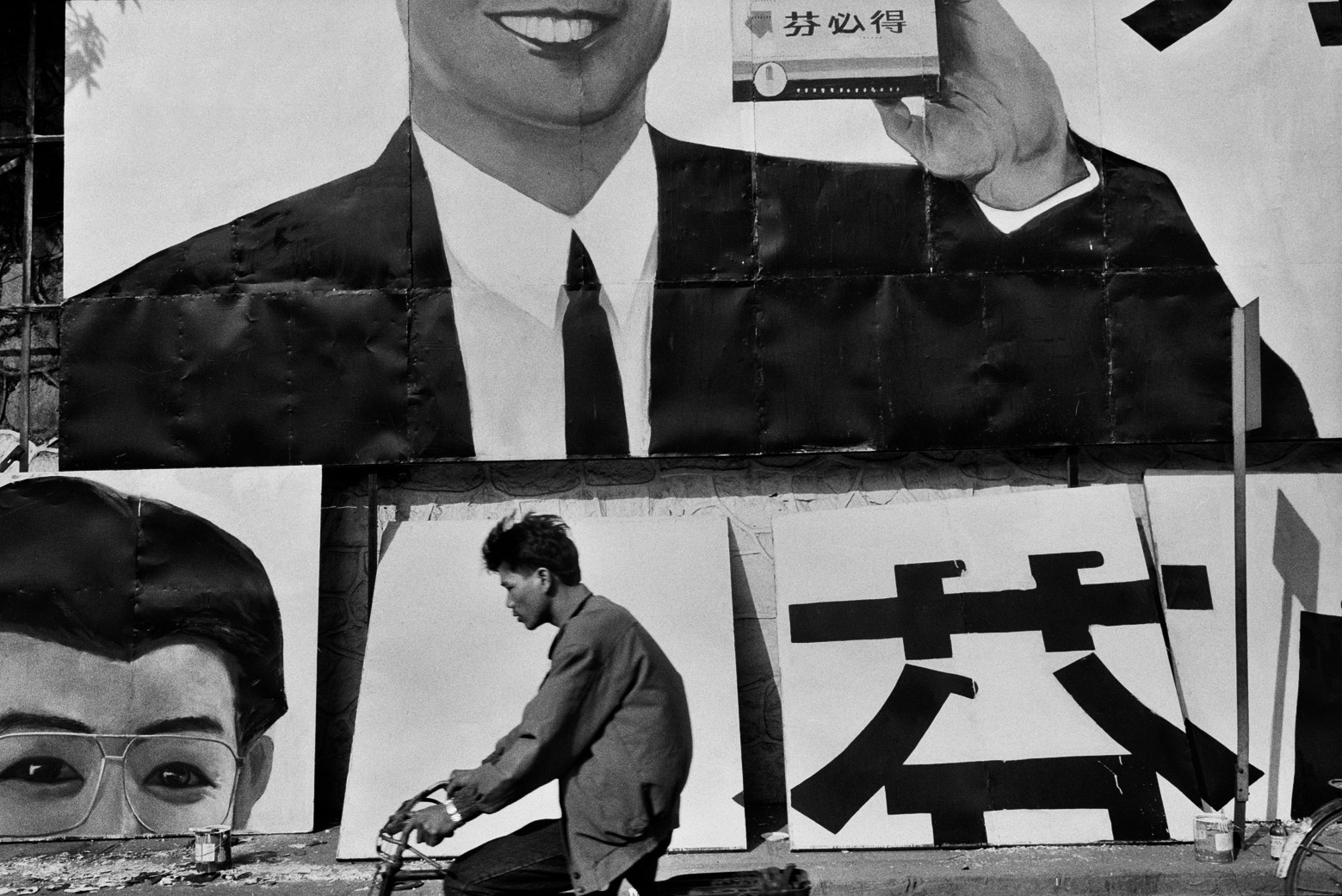

“The work I have done on China,” says Zachmann, “is very much about this conflict between reality and appearance.”

Back in Paris, he photographed Chinese mass migration and resettlement. He made friends with a Chinese expat who ran an import/export business and spent months learning the country’s history and customs. As he prepared a trip to Southeast Asia to find examples of Chinese diaspora, the expat volunteered to accompany Zachmann free of charge.

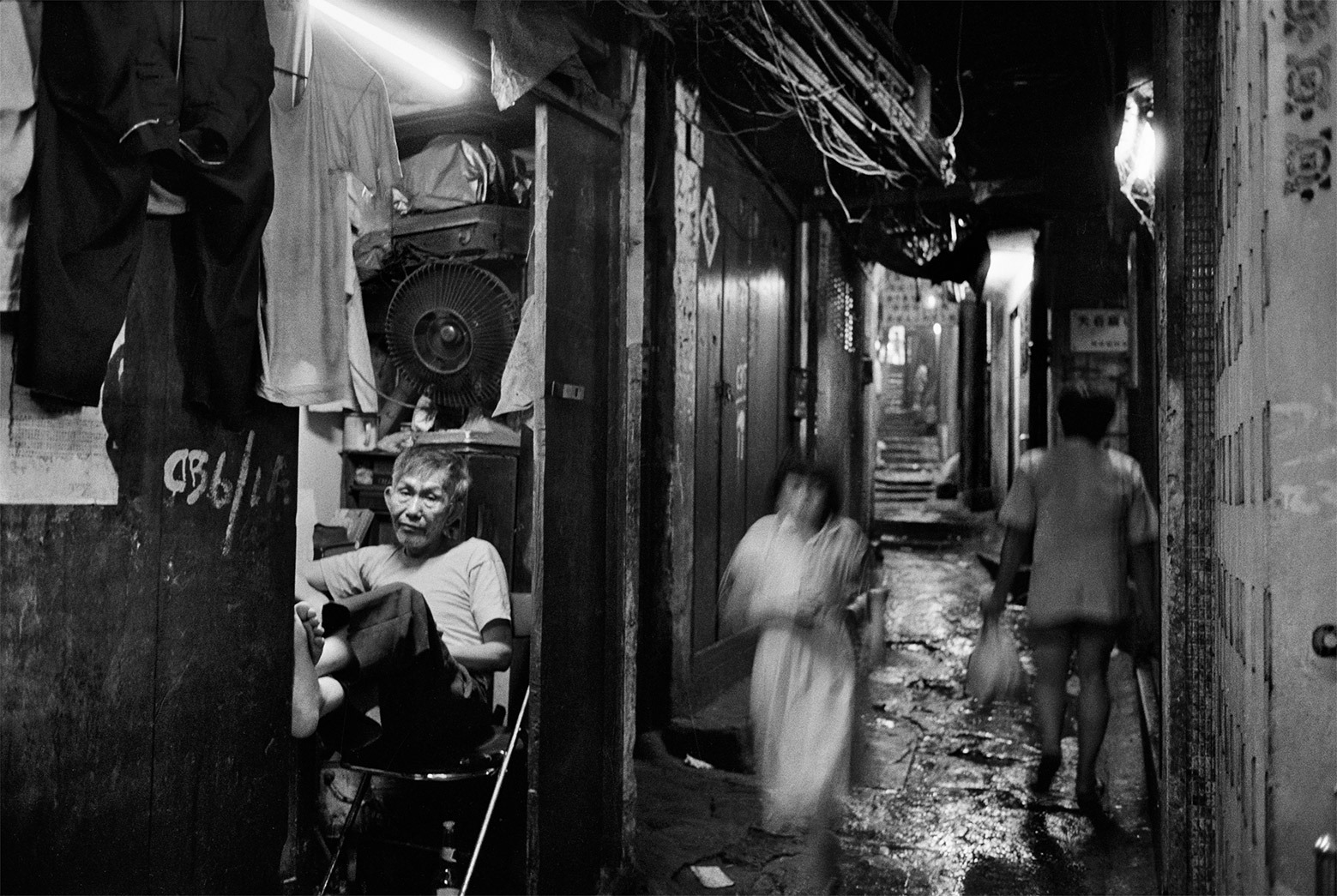

This time, as a tourist with a trusted guide, Zachmann was introduced to an unobstructed China. His black-and-white photographs show frenetic young men pressed against a clear jewelry case or steaming hot woks in narrow back alleys. His photographs are an early record of China transforming.

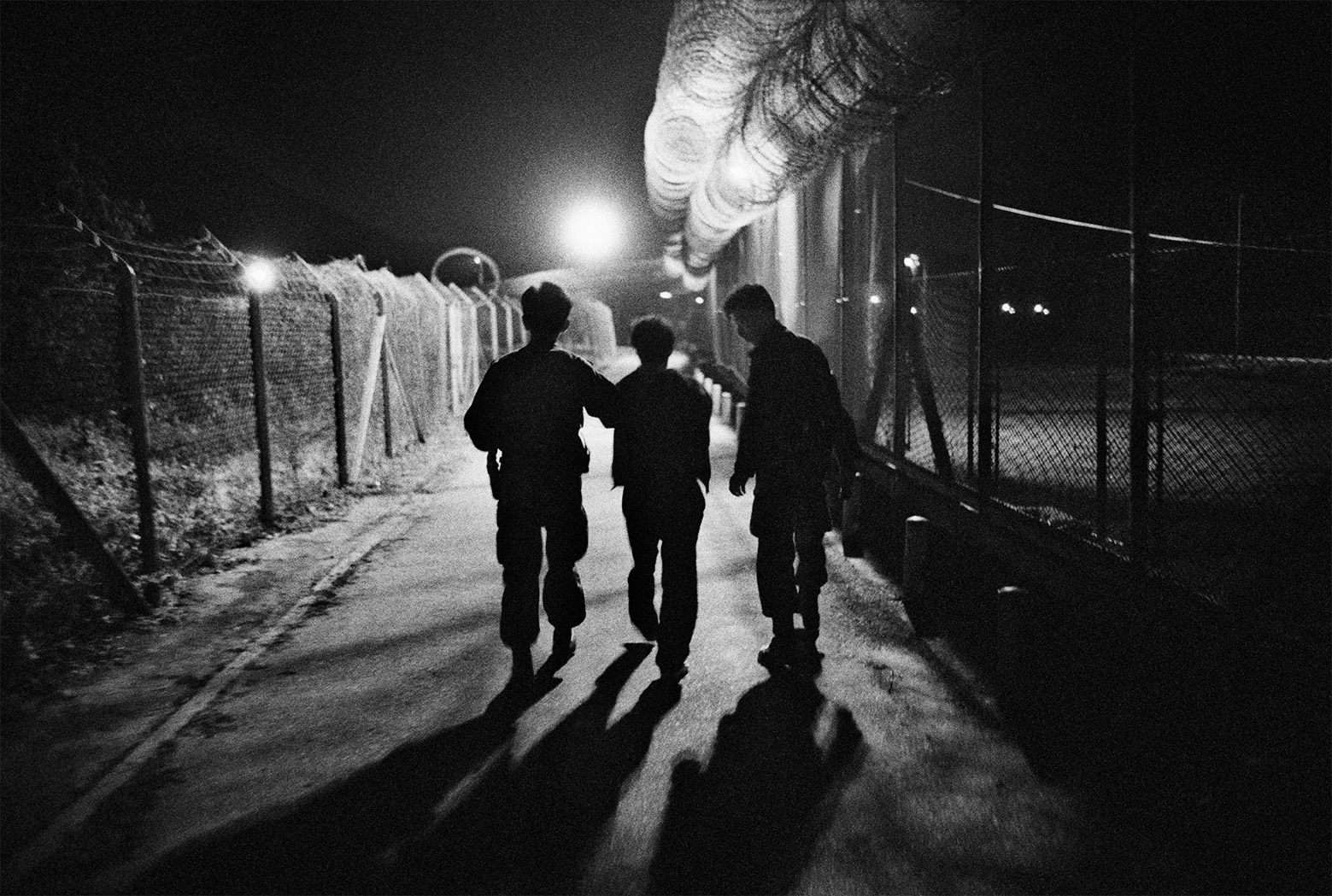

The transformation did not come without pain. In 1989, he witnessed thousands of students peacefully protesting at Tiananmen Square, looking to reform the Communist Party only to be brutally silenced. His photographs from this chapter capture jubilant crowds proudly holding handmade banners. Gradually, the sequence introduces images of an encroaching military. The chapter ends eerily with a photograph of a dark, blurry TV screen filled with an unending tight column of marching soldiers. Zachmann’s refusal to censor this chapter means the work will never be published or exhibited in China – a position based on his antipathy toward the Communist Party’s control. “How long will people accept to not be free?” Zachmann asks. “I’m sure it will come because they cannot carry on like this.”

In subsequent chapters, Zachmann separates his work into even more clearly defined sequences, emphasizing the difference between fact and fiction. A chapter called “Faux-Semblants,” or “False Pretenses,” shows square-framed, color photographs of real-estate billboards nestled in the Beijing and Shanghai landscape, blended to feel like photo collages. By including people walking in front of images of upcoming luxury high-rise apartments, Zachmann brings the real and imaginary into sharp contrast.

With no logical endpoint, Zachmann struggled to find a meaningful way to conclude the book. But the longevity of his work in China allowed him to grasp how quickly it was changing. He photographed elderly couples relocated by the government from their downtown Beijing home to the city’s outer limits. “They destroyed the old neighborhood,” he says. “Within a short period of time the history of China has sped up.”

The final chapter is a series of environmental portraits of grandparents and grandchildren that point to the deep chasms between generations of old and new China. To make the pictures, he traveled by plane, train and car to a small city outside Chengdu, in the Sichuan province, with a Chinese friend. He stayed with her family as a guest during the Chinese New Year when everyone returns home for the 10-day celebration. “What I liked is that I finished with the very free and intimate way of photographing through the family, through friends, through wandering villages,” said Zachmann. “I felt released in a way because I knew that maybe after my book I could start a new page.”

So Long, China exhibit will open on April 6, 2016 at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris.

Michael Bucher is a contributor at TIME LightBox.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com