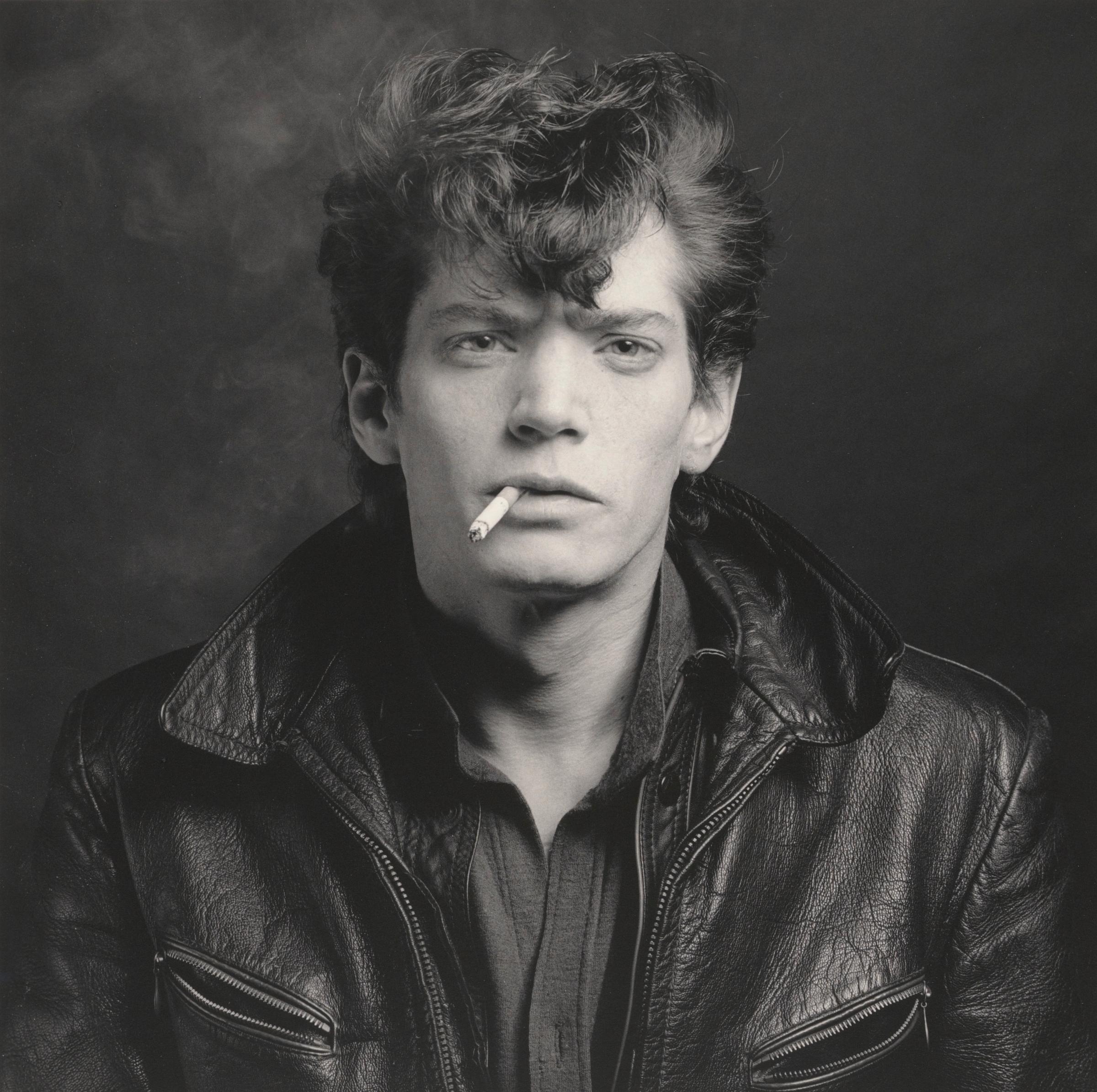

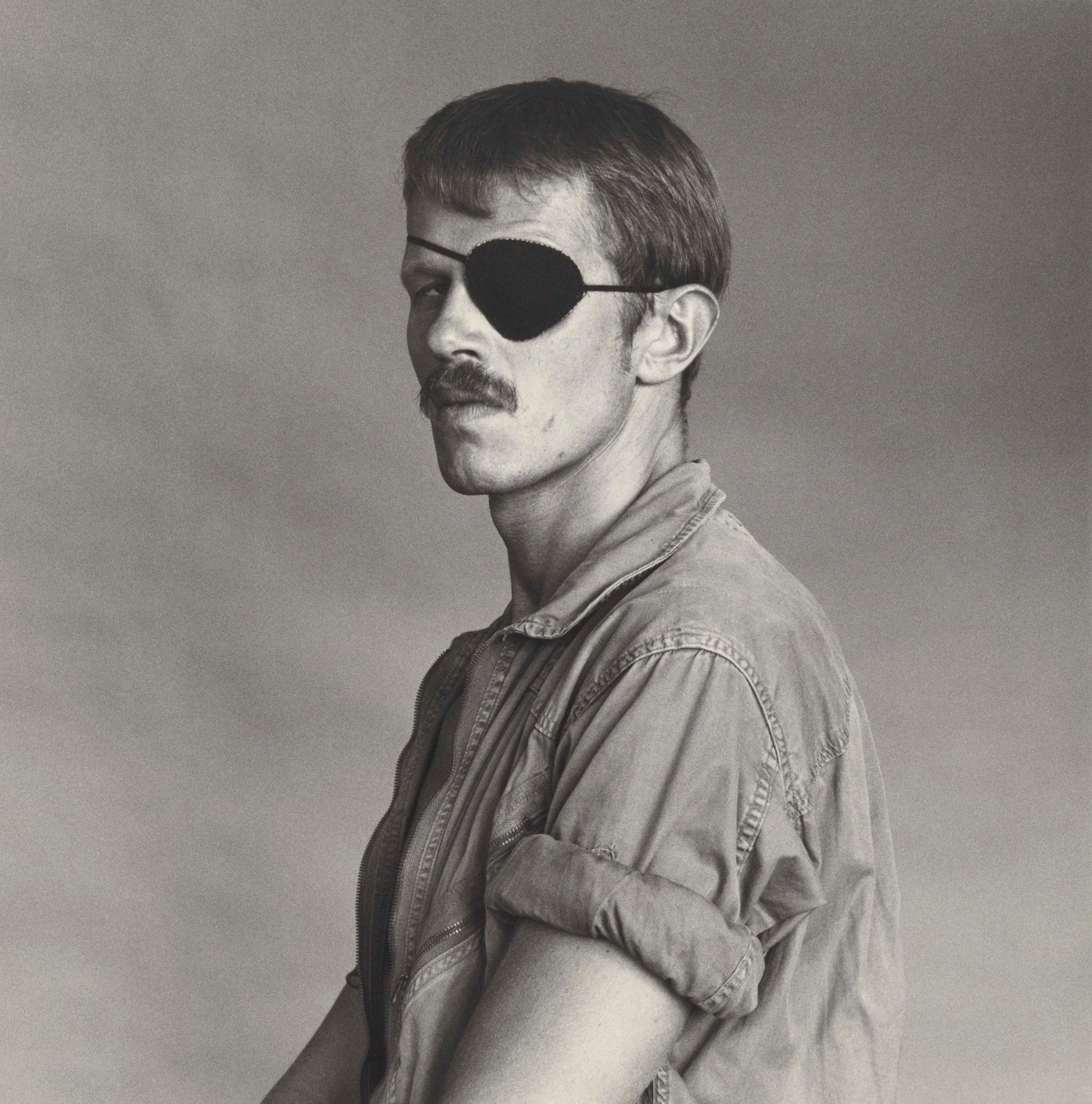

From fetishists to flowers, photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s meticulous works cast a classical approach on his subject matter. He created sharply-focused, carefully-posed images that were crisp and clean whether he was snapping a leather zipper mask or a wilting lily. While the late New York artist’s depiction of 1970s BDSM culture may be some of his most notable images, Mapplethorpe’s works extend far beyond latex suits and nude dudes.

Now, 27 years after his death, it’s the year of Mapplethorpe. There’s Phaidon’s new book, Mapplethorpe Flora: The Complete Flowers, and the recently opened shows at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Getty Museum, as well as HBO’s upcoming documentary, Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, which airs April 4. The collaborative exhibitions, Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium, illuminate his prolific output, featuring more than 300 works. LACMA displays a wide swath of his photos, ranging from sexualized snapshots reflecting gay male desire to portraits of notable creatives, like his close friend and former lover Patti Smith; Blondie frontwoman Debbie Harry; and pop art icon Andy Warhol. The exhibition also presents an inferential view of a long lost New York City, the edgy early days of midtown sex clubs, ascendant art stars, and the new trend of loft living. Plus, it showcases Mapplethorpe’s non-photographic works, including collages, jewelry design, and fashion pieces, unveiling the culture he so often experienced in private – in his everyday life, Mapplethorpe was confined by a pervasive anti-gay sentiment of his generation, but in his studio, he was truly free.

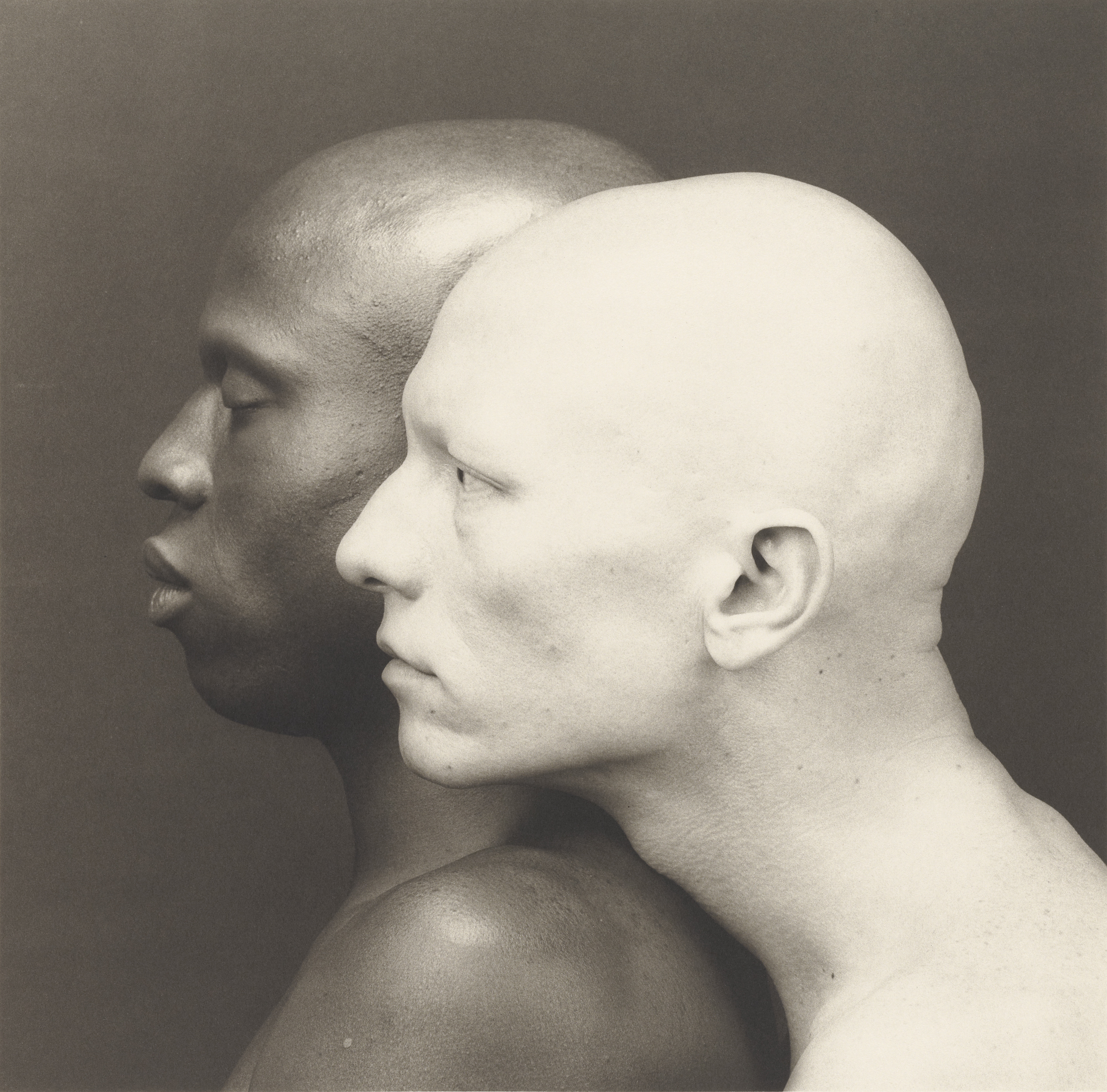

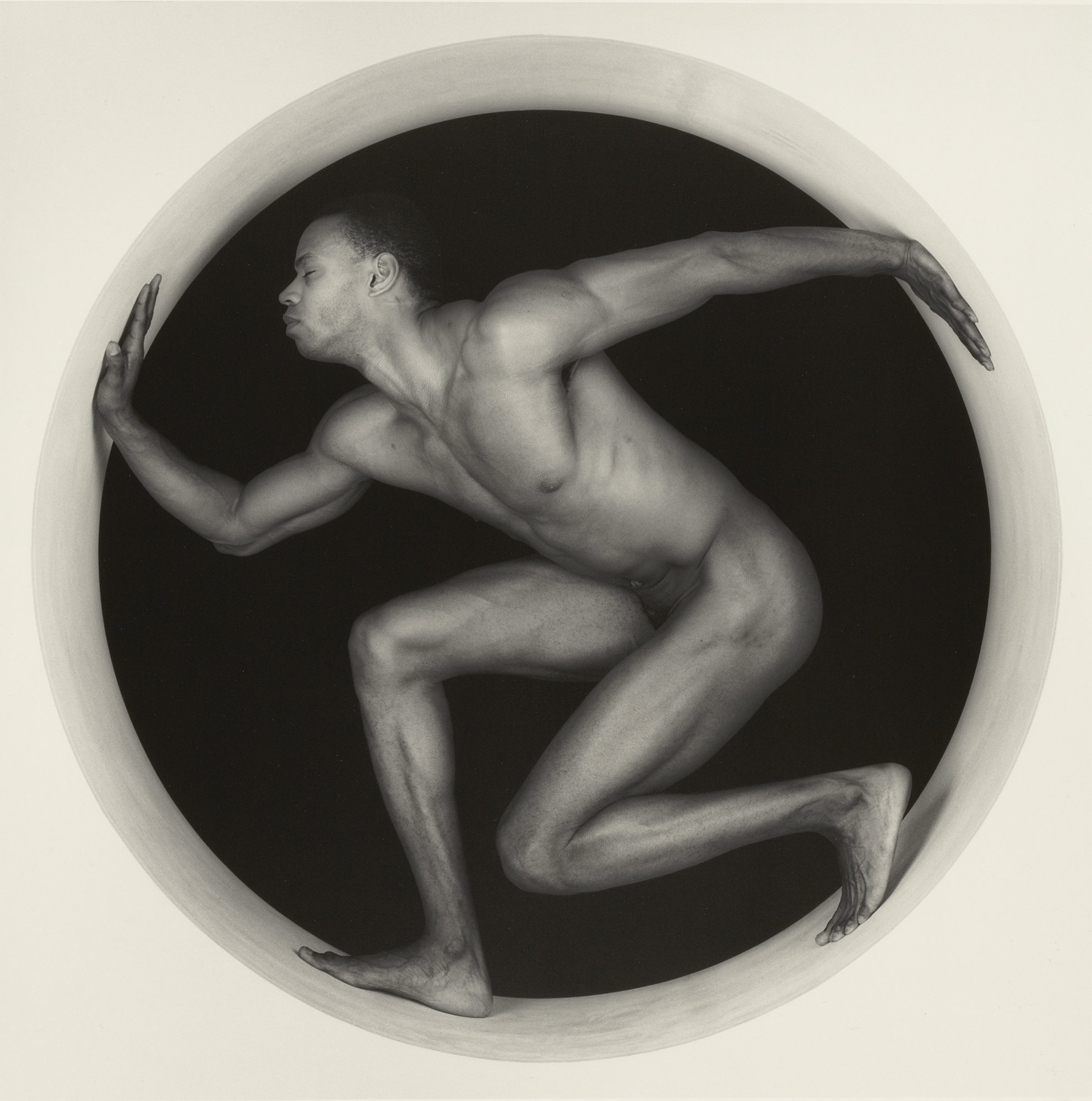

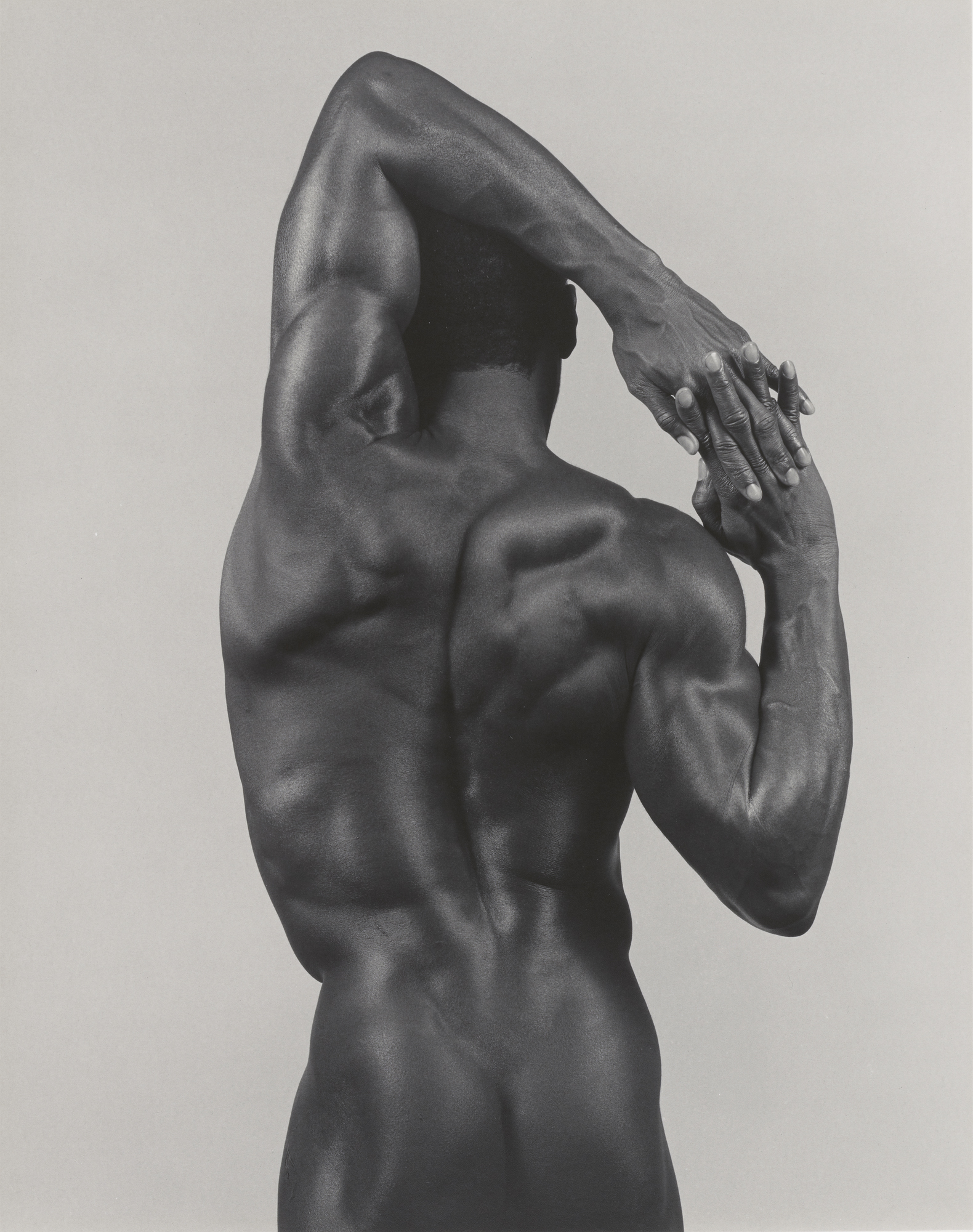

The Getty Museum displays numerous works too, including Mapplethorpe’s street photography, shot outside his Manhattan studio, as well as pieces firmly rooted in a sense of history. Capturing alabaster or onyx skin tones, Mapplethorpe was adept at rendering fleshy bodies almost as marblesque, like his 1987 image of Thomas, a nude African American man positioned in a circular structure, a form reminiscent to the imagery on ancient Grecian urns. His 1983 bust-like portrait of Ken Moody captures his nearly symmetrical physique silvery skin rendered in Mapplethorpe’s trademark black and white film. He also challenged gender norms with his photographs of Lisa Lyon, a female bodybuilder, whose muscular figure obfuscates the era’s standards of masculinity and femininity. Adjacent to the Getty exhibition is The Thrill of the Chase: The Wagstaff Collection of Photographs, an exploration of the influence of his relationship with art collector Sam Wagstaff, Mapplethorpe’s longtime partner and patron, featuring historic pieces from his expansive collection, which was acquired by the museum in 1984.

After his years of edgy and controversial works – his 1986 solo exhibition Black Males earned criticism for its seemingly racialized fetishization – Mapplethorpe abruptly shifted his focus to tulips and blossoms, which isn’t that shocking when you consider that flowers are the reproductive organs of plants. But in art, a flower is never just a flower. They’re symbols, like those 17th Century Flemish still-lifes depicting banquets and bouquets that weren’t only commemorations of luxuries; they were a memento mori, a reminder that every flower lilts and all feasts come to an end. For Mapplethorpe, as he was photographing these still-lifes, his own life was moving towards death. He contracted AIDS in 1986 and died three years later. In the images he left behind, Mapplethorpe perhaps reveals the ethos driving his practice: joyful moments inevitably turn into memories, but a photograph lives forever.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Your Vote Is Safe

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- Column: Fear and Hoping in Ohio

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com