It’s a Saturday night in a crowded mall in one of Hong Kong’s northern suburbs, and Edward Leung is trying to sell hundreds of shoppers on a decidedly uncommercial message. “Ignite the revolution to reclaim our Hong Kong!” he shouts, fist in the air. Revolution is not usually fashionable in Hong Kong, a global financial hub that ranks among the planet’s more materialistic cities. But Leung—a 24-year-old philosophy major with round, thick-rimmed glasses, who looks more classroom geek than radical agitator—draws, if not support, certainly curiosity. For one thing, he is running in a by-election for a seat in the local legislature. For another, he is out on bail on a charge of rioting. But most important, Leung is getting some attention because, like him, many in Hong Kong are furious with their sovereign overlord: China.

Leung is the face of Hong Kong Indigenous, one of several local groups pushing for greater autonomy or even independence from China, which took back the metropolis from Britain in 1997. He was thrust to prominence on a night of unrest in early February. Authorities attempted to stop unlicensed hawkers from peddling fish balls and tofu on sticks to Chinese New Year revelers in Mong Kok, a colorful district known for bargain items and questionable characters. Leung viewed the clear-out as an attack on a cherished Hong Kong culinary custom, and he helped rally hundreds of protesters who occupied large sections of road and set trash cans and other objects on fire. Some hurled bricks at police. In one incident, protesters wielding sticks and boards attacked a fallen officer before his colleague drew a pistol and fired two shots into the air—all a level of violence seldom witnessed in Hong Kong.

Read More: Hong Kong’s Existential Anxieties Continue to Mount in the Face of China’s Encroachment

“If the oppression from the government is getting bigger and bigger, we will strike back,” says Leung. “We have no fear.” He and about 50 other people were charged with rioting, an offense not prosecuted in the city since the 1960s, when Hong Kong was racked by labor unrest, as well as the spillover of Cultural Revolution turmoil across the border in mainland China. On Feb. 21 police found what they said were suspicious chemicals in a flat where Leung’s Hong Kong Indigenous co-founder, Ray Wong, was discovered and arrested after two weeks on the run.

On the surface, life in Hong Kong, especially its main island, which includes downtown, goes on as always: efficient, productive, glittering. Deals and fortunes are made, and copious amounts of money spent. The roads brim with Mercs and Beemers. The government’s foreign-exchange reserves add up to some $360 billion. Hong Kong seems to want for nothing.

But there’s a dark side. The economy is controlled by a handful of big local and mainland companies, leading to one of the world’s highest Gini coefficients, a measure of income inequality. Some 20% of the 7.2 million population live below the poverty line (about $400 of income a month for one person). For the vast majority of people, owning a home in what is one of the world’s costliest cities has become a pipe dream. Says recent university graduate Mary Law: “There’s very little upward social mobility and a lot of downward.”

Many in Hong Kong blame local officials and lawmakers for this malaise, which has been worsening for some years now. But they are angriest with Beijing. Hong Kong was returned to China under a “one country, two systems” formula whereby the city would remain largely autonomous and retain the civil freedoms that set it apart from the rest of China. Beijing seems to be eroding those freedoms, however, whether directly or through the city’s unpopular chief executive, or head of government, Leung Chun-ying, whom many citizens believe puts China’s interests before Hong Kong’s.

Five years after the 1997 handover, Hong Kong authorities tried to introduce a security law similar to that enforced on the mainland, which could restrict free speech and assembly. In 2012 officials proposed implementing “national education” for schoolchildren, which critics say is akin to Communist Party brainwashing. In both cases mass protests by ordinary folk forced the government to back down.

Read More: Hong Kong Sees Violent Start to Chinese New Year as Protesters Clash With Police

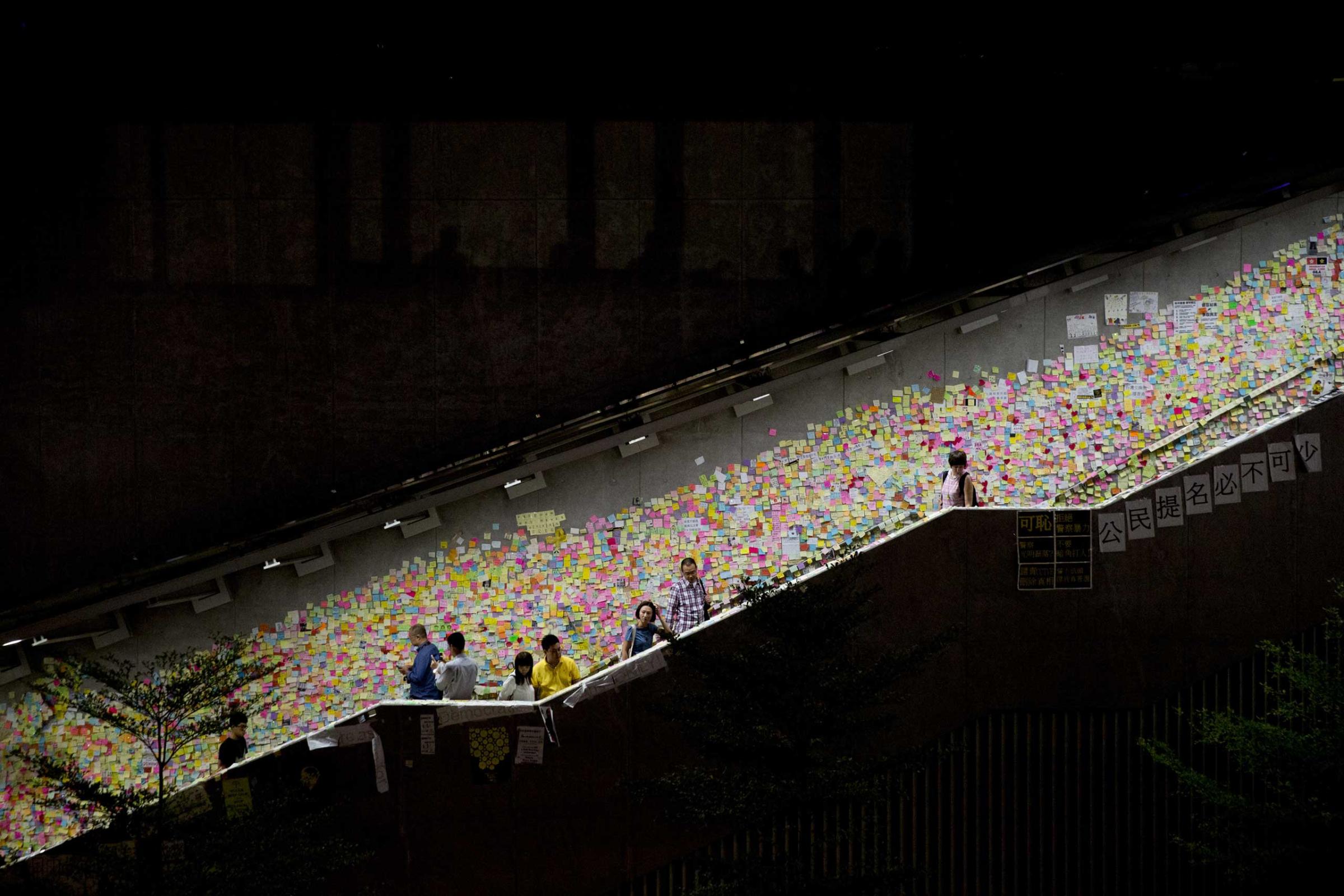

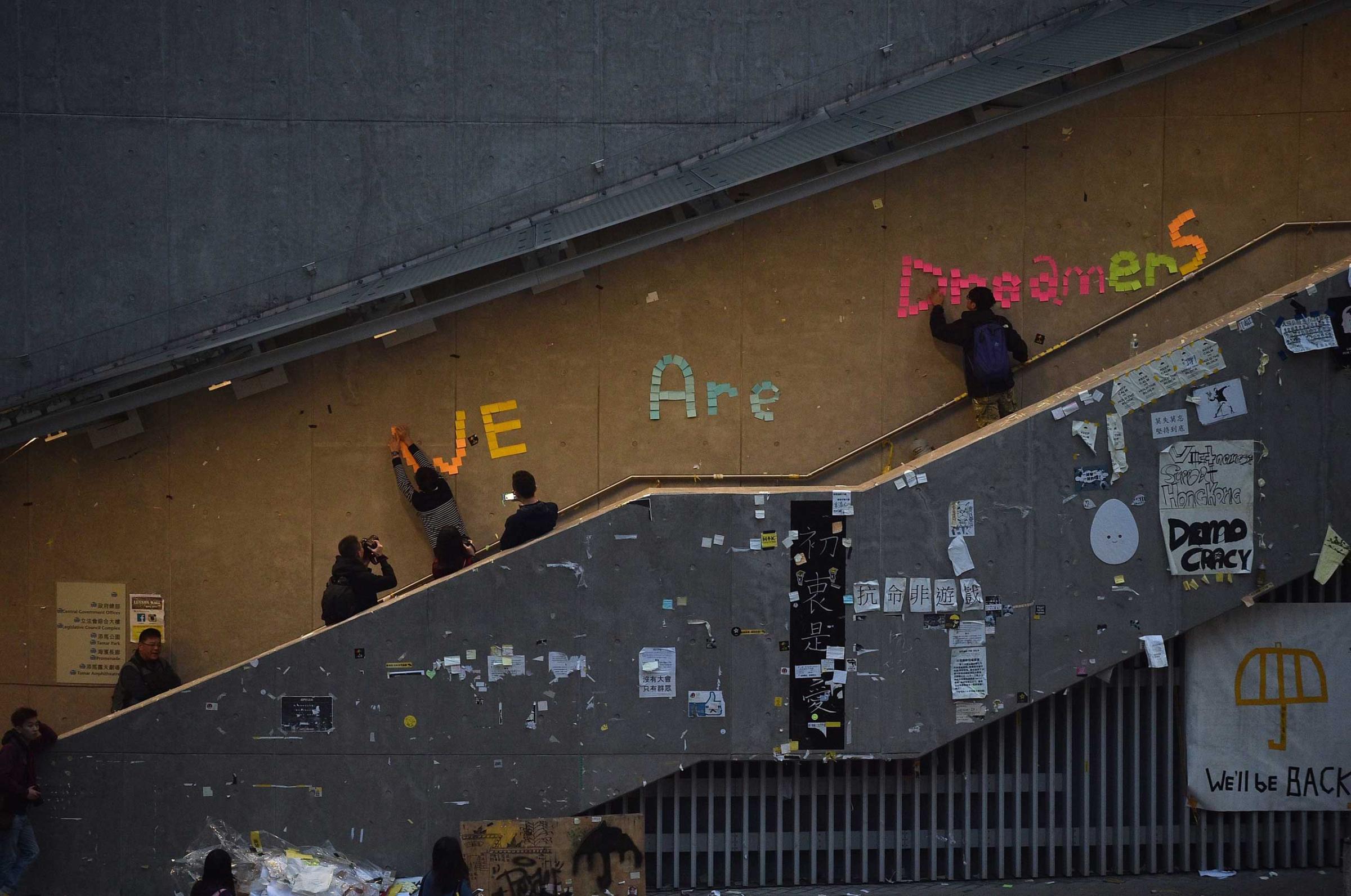

Then, in 2014, Beijing announced that only up to three candidates vetted by an Establishment-heavy committee could run for the first direct election in 2017 for the job of chief executive. That decree helped kindle the so-called Umbrella Revolution and scuttled the election scheme’s passage in the legislature.

The Hong Kong Journalists Association says that press freedom is deteriorating and that intimidation of editors and reporters and self-censorship are on the increase. And recently, a Hong Kong man who, with his four colleagues, sold sensational books critical of the Chinese leadership turned up in detention on the mainland without formally crossing the border—sparking widespread concern that he was kidnapped in Hong Kong by agents acting for Beijing. If true, that would be an egregious breach of local law and autonomy. (Two of the booksellers, who “confessed” on Chinese TV that they illegally distributed books on the mainland, have returned to Hong Kong.)

“We’ve seen booksellers disappear, academic and media freedom shrinking, and growing disaffection among Hong Kong’s youth,” U.S. Senator and presidential candidate Marco Rubio, who co-chairs the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, said in a Feb. 26 statement. “These most recent actions call into direct question Beijing’s commitment to the principle of ‘one country, two systems.’”

Read More: Hong Kong Is Ready for Democracy, but China Isn’t Ready for a Free Hong Kong

Differences over identity prevail too. Many Hong Kongers resent mainland immigrants and visitors snapping up everything from real estate to school places to even infant formula. (Mainland Chinese don’t trust their own brands.) Just 8.8% of citizens regard themselves solely as “Chinese,” down from almost one-third in 1997, the year of the handover, according to 2014 polling by the Chinese University of Hong Kong. For many residents, says Sonny Lo, an associate dean at the Hong Kong Institute of Education, “the ‘two systems’ are more important than ‘one country.’” While the Mong Kok riot may have started with street food, it reflected a sense that Hong Kong’s way of life is under siege.

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

That sense is partly fueling the rise of what citizens call localism, of which groups like Hong Kong Indigenous constitute the extreme edge. Most Hong Kong residents reject violence of any kind—the city is one of the world’s safest. Yet, even after the Mong Kok riot, Leung won more than 15% of the vote, finishing third behind winner Alvin Yeung, a mainstream democrat, and a pro-Beijing candidate. Admits Yeung: “Localism is now a major part of Hong Kong politics.”

A major part—and a major complication. Hong Kong cannot survive as an independent entity even if China’s leaders were to countenance it—which they wouldn’t. The city relies on the mainland for much of its food and water, and its economy is completely intertwined with China’s. “The simple fact is that we are Chinese, and so-called Hong Kong autonomy—it’s a fantasy,” says Regina Ip, a legislator from the pro-Beijing New People’s Party. (Ip is a former secretary for security who resigned in 2003 after the government’s failure to enact the security law.) If a “rebellious” Hong Kong takes on Beijing, says Ip, mainland officials might impose more restrictions on the territory: “The radicals, who are pushing and pushing, could be doing a disservice to Hong Kong.”

China’s top official in Hong Kong, Zhang Xiaoming, brands groups like Leung’s as “radical separatists” with terrorist “tendencies.” The language is similar to what Chinese leaders use for anti-Beijing incidents in Xinjiang and Tibet, which are sternly put down, and it comes at a time when Chinese President Xi Jinping is suppressing all manner of dissent on the mainland. “What do you do with violent radical separatists? You send in the People’s Liberation Army,” says David Zweig, a China scholar at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. “There are forces that want to portray Hong Kong as another case of political instability on the periphery. That is a really big thing. It means they can use extraordinary methods.”

Though the model seems already marginalized, “one country, two systems” was projected to last for 50 years after the 1997 handover, until 2047. Then, all bets are off, and Beijing can constitutionally do what it wants with Hong Kong. “For older people, that’s something they don’t have to worry about,” says Baggio Leung, the 29-year-old convener of Youngspiration, another localist group. “I will still be alive, so that’s something that I need to fix.” He and, increasingly, many of his fellow Hong Kongers.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Simon Lewis/Hong Kong at simon_daniel.lewis@timeasia.com