March is Women’s History Month, a good time to visit historic places that tell the stories of extraordinary women who have shaped the American experience. While my new book 50 Great American Places documents these places, it also recognizes the women who led the effort to preserve these sites. Here are just a few examples:

Seneca Falls, N.Y.

A small chapel in an upstate New York factory town was an unlikely setting for the world’s first convention on women’s rights. Yet because of the powerful leadership of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and their allies, 300 people—women and men—gathered there on July 19 and 20, 1848, and adopted a document, the Declaration of Sentiments, that has become a touchstone of American democracy. Stanton’s home in Seneca Falls is part of a national historic park that includes the Wesleyan Chapel, the site of the convention, and two homes in nearby Waterloo connected to planning the convention and drafting the declaration. A few miles east in Auburn, the famous Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman lived for more than 50 years on land purchased from William Seward—abolitionist, U.S. Senator, and Secretary of State. Their homes open to the public and provide powerful examples of the close ties between the women’s rights and abolition movements in the 19th century and the continuing struggle for equality today.

Hartford, Conn.

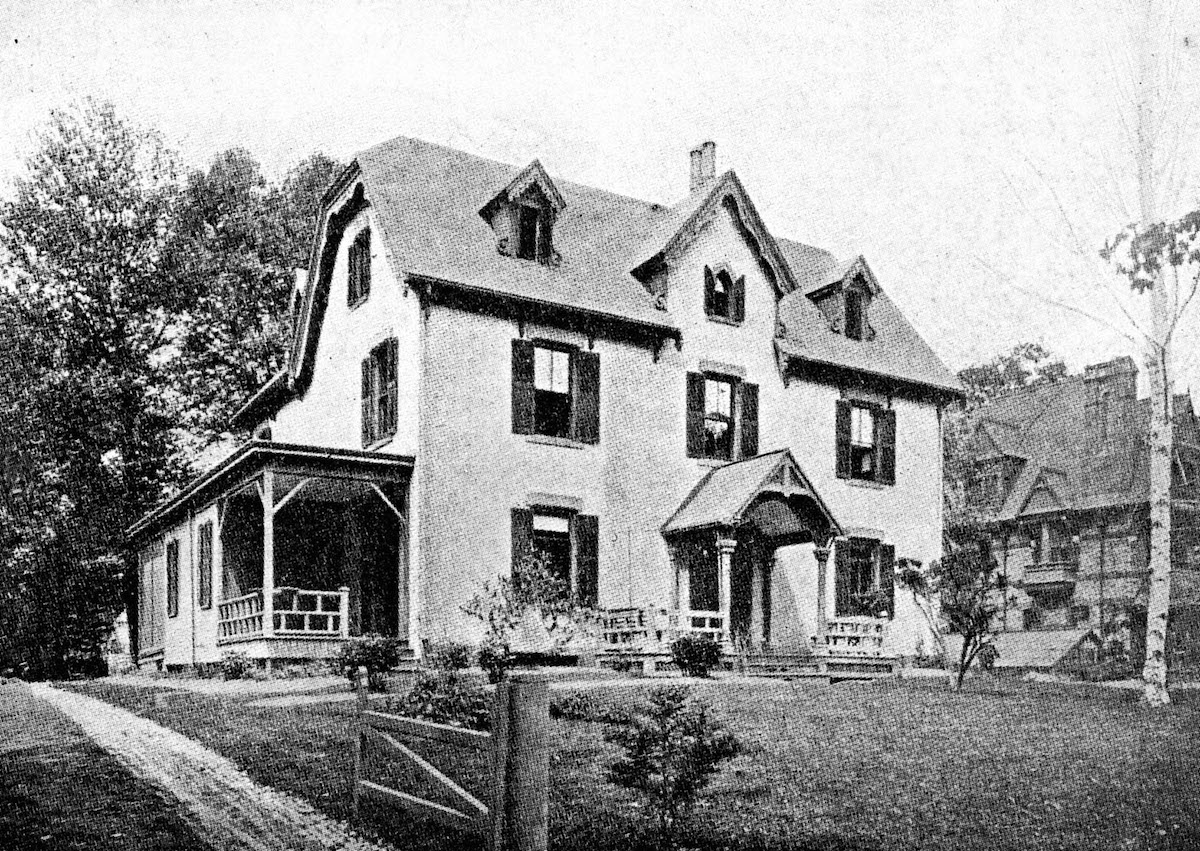

By the time her family purchased their home at 77 Forest St. in 1873, Harriet Beecher Stowe was already the most famous woman in America. Her novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was the number-two bestselling book of the 19th century—behind only the Bible—and brought the issue of slavery and its abolition into the forefront of America’s social and political conscience. The Stowe House is located in Nook Farm, a 140-acre parcel purchased by Stowe’s brother-in-law John Hooker and lawyer Francis Gillette in 1853. In the years before and after the Civil War, the neighborhood attracted writers, ministers, politicians, abolitionists and social reformers who shared Hooker’s commitment to social justice and political reform. Stowe and her husband Calvin built a Gothic Revival style home in Nook Farm in 1864 and moved in 1873 to Forest Street. (The following year, a young author who wrote under the name of Mark Twain built a large Victorian house next door. Stowe and Twain were neighbors for 20 years.)

In the decade before the Civil War, Stowe had become an international celebrity and one of America’s foremost anti-slavery advocates. The popularity of Uncle Tom’s Cabin was global, especially in Great Britain, where the book inspired songs, games, plays and commercial products such as soap, scarves, and pottery. At the invitation of antislavery groups in Europe, Stowe journeyed with her family and friends to England, Scotland, France, Italy and Switzerland. Huge crowds greeted her at every stop and she received many gifts from royalty, organizations, and admirers, including a 26-volume petition supporting abolition (now displayed at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center) signed by more than 560,000 British women. The Stowe Center maintains a program that “promotes vibrant discussion of [Stowe’s] life and work and inspires commitment to social justice and positive change.”

Red Cloud, Neb.

When Willa Cather was 9, her family moved to a farm on the prairie near this small town. She left Red Cloud 12 years later, seldom returning throughout her life. Yet during her brief time there, she had stored away enough impressions of life, people and especially the land to create novels and stories that captured America’s frontier experience. Everything about her years in Red Cloud—the train depot, the opera house, the bank, the hardships of farming, the barrenness and beauty of the prairie, the pleasures and pain of small town life, and the triumphs and tragedies of immigrant families—later appeared in her novels, stories and poetry.

Beginning in 1912, she produced 12 novels and dozens of short stories creating a rich imaginary world grounded in real places she had lived and visited. Her Prairie Trilogy—O Pioneers! (1913); Song of the Lark (1915); and My Antonia (1918)—established her reputation as a master of regionalism whose novels chronicled the closing decades of America’s frontier period. As her characters faced relentless physical, economic and social pressures, Cather created unforgettable scenes of despair and the bleakness of the Nebraska prairie. She also, however, could suggest the possibilities of hope and renewal. One of the famous scenes in My Antonia described a the silhouette of a plough as the sun set on the prairie: “Magnified across the distance by the horizontal light, (the plough) was exactly contained within the circle of the disc; the handles, the tongue, the share—black against the molten red. There it was, heroic in size, a picture writing on the sun.” This image is the logo of the Willa Cather Foundation that sponsors tours of Cather’s home and other landmarks, conferences, educational programs, and hiking trails at the Willa Cather Memorial Prairie, a 600-acre park south of town described as a “never-been-plowed prairie ecosystem that preserves plants and wildlife of pre-pioneer days.”

Behind the Scenes

These historic sites and many others would not exist today were it not for the efforts of women who were pioneers for historic preservation. Katherine Seymour Day, led the effort to save the Stowe and Twain houses and several others in Hartford’s Nook Farm neighborhood. In the 1950s, Mildred Bennett created the Willa Cather Foundation that has transformed Red Cloud into a living literary monument. At the forefront of this movement was the Mount Vernon Ladies Association who saved George Washington’s home in Virginia and continues to manage this landmark today.

Other preservation pioneers include Virginia McClurg at Mesa Verde in Colorado and Adina de Zavala and Claire Driscoll at The Alamo in San Antonio, Tex. Most of these women did their work in relative anonymity. A rare exception was former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis who stood up against a proposal in the 1970s to build a skyscraper on top of New York’s Grand Central Terminal. “Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees,” she wrote, “stripped of all her proud moments, until there will be nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children?”

Brent D. Glass, Director Emeritus of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, is the author of 50 Great American Places: Essential Historic Sites Across the U.S.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com