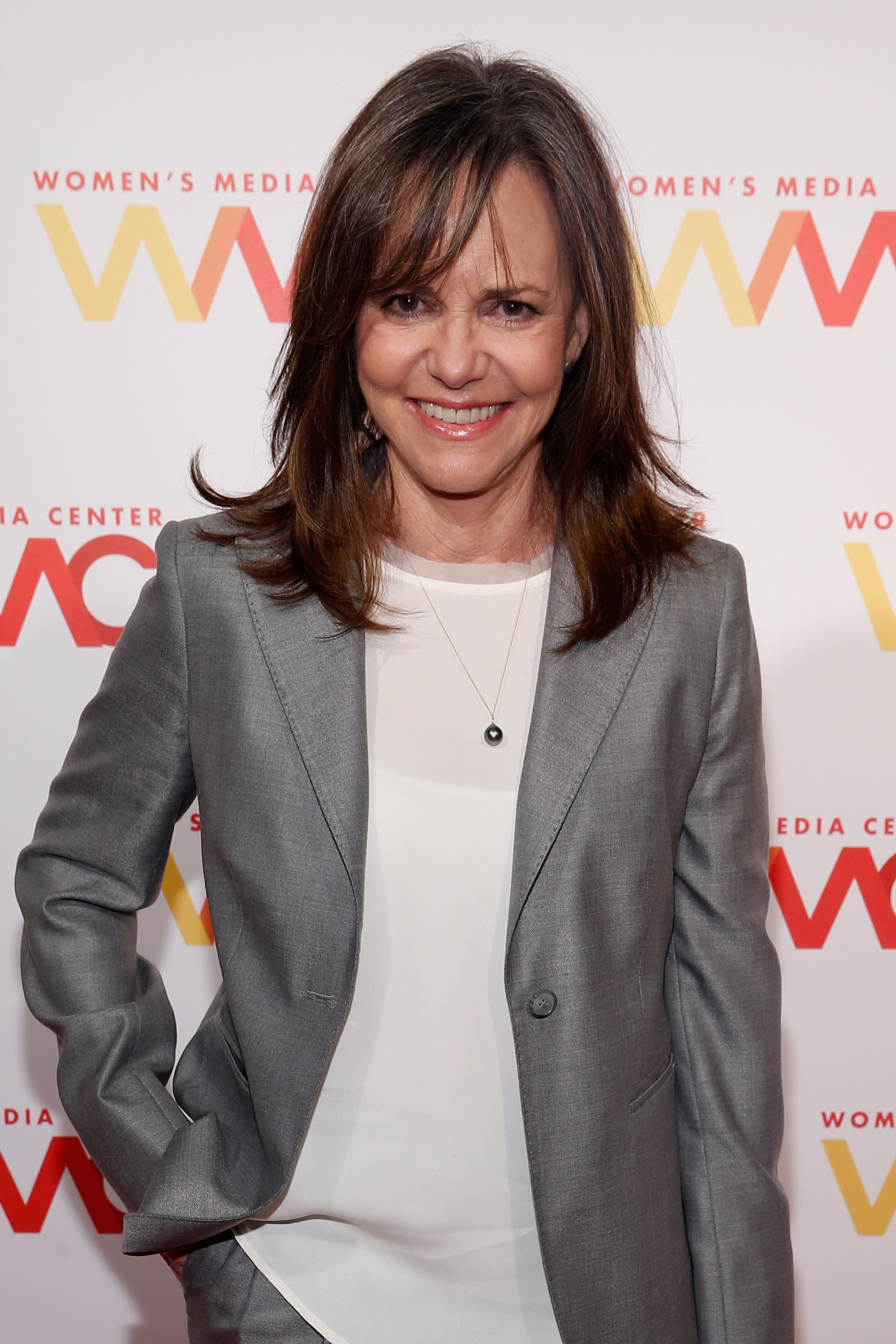

Over the last decade, Sally Field has kept a relatively low profile on the big screen. There have been some notable exceptions—namely, her Oscar-nominated turn as Mary Todd Lincoln in 2012’s Lincoln and her recurring role as Aunt May in the Spider-Man movies—but she has otherwise focused her efforts on theater, television and supporting LGBT rights and women’s issues. But with Hello, My Name Is Doris (March 11), co-written and directed by Wet Hot American Summer scribe Michael Showalter, Field returns to top billing as an eccentric office worker with a mega-crush on her hunky, half-her-age coworker (Max Greenfield).

For Field, the rarity of all the things Doris does right—recognizing the sexual agency of a (fictional) woman in her 60s and offering a multilayered starring role to a (real) woman in her 60s—underscore just how far Hollywood still has to go in fighting the twin scourges of sexism and ageism. Field talked to TIME about how Hollywood has changed throughout her 50-year career, what she’s currently binge-watching and how she and her granddaughters are faring in the debate over Bernie Sanders versus Hillary Clinton.

TIME: There are not many movies where the female love interest is older than the male. Is that part of why Doris appealed to you?

Sally Field: The gender reversal was secondary to the story of a coming of age of a person of age. I saw the love-affair part of it almost as part of her coming out of her shell as if she were 13. To me, in playing the character, age was never part of it, because it never occurred to her.

Can you compare love in your 60s to love as a teenager?

As time goes on, our faces and our bodies change, they cave in and they puff out and collapse, but inside we’re the same. When you have that feeling, when you have a mad, passionate crush on someone, it’s the same when you’re 70 as when you’re 13. You’re awkward and you’re afraid you’re doing the wrong thing and you put yourself out there in ways you don’t even think about. We stay who we are no matter how old we get.

At this stage in your career are there roles you just won’t take?

Yeah, absolutely. I just don’t want to do what I don’t want to do anymore, and I don’t need to, so I won’t. Roles like Doris, it’s not that they don’t come around very often, they don’t come around ever. What is frustrating is that the roles I read [are] cartoonish. They’re not three-dimensional characters. They’re not really what it’s like to be a woman in their 60s and 70s, what they’re facing, whether it is with their grown children or their grandchildren or their lives or their husbands.

You’ve done less in film in the past decade than in theater and television. Are there better roles there?

Certainly there have been for me. I just go where I feel the most interesting work is. Having a long-term career is really about learning how to ride it and not be rigid. Keep asking yourself, What really blows my skirts up? To me it’s finding the work.

Would you consider going back to TV?

Sure, I would absolutely go back to TV if it was a role that I thought, ‘Wow, that would be really a kick.’ I doubt that it would be network television. But I think right now what’s happening in cable television is fabulous. Since I started in television in 1964, everything was so rigid. Everybody would implode if my bellybutton showed in my ridiculous two-piece bathing suits. It’s so different now to see that television really is the engine that’s driving the edge of telling human stories now, much more than film.

Is there anything you’re binge-watching right now?

I watched all of the second season of Transparent, I’m catching up on Mozart in the Jungle and I know the new season of Girls has come out, and I’ve watched all of Veep. You name it. Matter of fact, I ought to be asking you, is there something I missed?

Oh goodness, Fargo, The Americans.

Of course, I always watch [The Americans] because that’s my darling Matthew Rhys, who was in Brothers and Sisters with me.

Why do you think Hollywood has been so reluctant to acknowledge the sexuality of a woman in her 60s?

It’s hard for me to answer that because obviously Hollywood is so hard on women altogether. I’ve been in this business for 53 years or something, and part of me, I hate to admit it, has sort of accepted it as the status quo. The industry has always, but certainly now to a huge degree, played to young men, and made a self-fulfilling prophecy about films that aren’t directed toward young men by saying there’s no audience for it. So they put no money in it, they don’t promote it, and then when it doesn’t make as much money as the films for young boys, they say, “You see?” There’s a whole lot of people who want to see stories that they can identify with, and they’re not male and they’re not white and they’re not young.

How blatant is ageism in Hollywood?

It’s blatant in the country. It’s affected me in ways that I can’t even calculate. Because I grew up in the business and I’ve been here for so long, I’ve been affected by images of women my entire existence and unconsciously both adapted to them, tried to fit into them, and then also at the same time went, “Oh, F-U, I can’t do this.” It’s always a battle inside myself, and I know that most of the women in this country feel that, even if they’re not actors. It isn’t just Hollywood. Hollywood illuminates it and perpetuates it, but it is what this country is in some ways.

Have you seen this level of discussion about equality before?

There was bits of it here and there. The actors in my generation, we all knew what it was like to go in and have wonderful stories that you wanted to put into development, and hearing the reaction, “We don’t want little Sally doing that.” Doing what? A story about nurses in Vietnam, things like that. I remember Diane Keaton once complained that men had so many more opportunities. She was shot down for being a whiner. I remember thinking, Wow. It was brave of her, but it wasn’t taken as any kind of serious comment. I felt—and Jane Fonda, and Goldie [Hawn]—that all you could do was just keep on keeping on. But this wave is bigger—it’s much more inclusive. It is not only about women, it is about people of color, and that’s a bigger, louder voice. I might also say it’s because there are men involved—I hate to say it—so it’s taken more seriously. I think if it were just women, probably it would not have quite the effect.

What did you think of the changes the Academy made?

I didn’t read all of them, so I can’t answer correctly. I did know the one where they said voting rights would be restricted based on how frequently you worked, and I did have a reaction inside my stomach that went, ugh. Because you think of all the great actors whose participation you’d like to have. Claudette Colbert retired, but wouldn’t you want her voting? I think so. She probably didn’t give a rat’s ass. But part of me thinks it’s too cut and dry. You start to think, Wait a minute, already I’m on the outs because I didn’t work this year? Already the Screen Actors Guild does that.

Did you watch the Oscars this year?

I watched some of it. But I was reading a good book, so I was looking up and looking down and then muting it and turning it on.

Can I ask what book?

I’ve found this writer that I love so much. He just passed away and it kills me because I would have liked to have met him. He lived in Holt, Colorado, and he has about six books. His name is Kent Haruf. So I was completely involved in this farm at the turn of the century in Colorado.

To what extent did your roles in movies like Norma Rae, in which you played an activist, influence your real-life identity as an activist?

The film was important but not half as important as my meeting and knowing [director] Marty Ritt, and having him in my life until he passed away. He opened me up. He called himself an old leftie, and his whole history of what he’d been through during the Depression and then being blacklisted, how it influenced his voice and how true to that voice he stayed—that eventually started to open me up to where my voice was, which obviously was in helping women all over the world who feel trapped by societies that are a lot worse than this one towards women. I feel strongly if we cannot balance this planet with the voices of women, we will never heal.

You’ve been a longtime advocate for LGBT rights. What issue is your biggest priority right now?

I went to Houston and tried to help on [the “bathroom bill“] vote before it happened. But it happened. I can’t really determine where I could be of value, so when Chad Griffiths, who is the head of the Human Rights Campaign, calls me and says “Can you pack your bag and be so-and-so,” I would.

You stumped for Hillary Clinton in 2008. Will you lend your voice to this campaign?

Oh my God, yes. If it hadn’t been for this [movie], I’d be there now!

What do you make of suggestions that young women have a responsibility to vote for Clinton? Is there an intersection between feminism and voting for a female candidate?

I think it’s miraculous that she is female, and it’s almost secondary to the fact that she’s way qualified, would be a brilliant President. Just like [with] Barack Obama, it was a huge factor that he was African-American, but he was also brilliant, and has been brilliant. I really can’t understand the battle. I hear young women, my granddaughters even, wanting to back Bernie, and I want to tear my hair out, and I jump up and down and go, “What?!” Not that he’s not a lovely man. But then we have a hard time hearing each other. Because they’re a different generation, they’re automatically more inclusive, and they’re not knowing where we all came from. And why should they? But it is good to know. It’s important.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com