This piece is part of an ongoing series on the unsung women of history. Read more here.

Is it possible for a woman to be single and happy? Even after multiple waves of feminist revolution and backlash, the answer to that question still comes with caveats: Yes, if she’s young. And it depends what you mean by happy…

Marjorie Hillis had no such doubts.

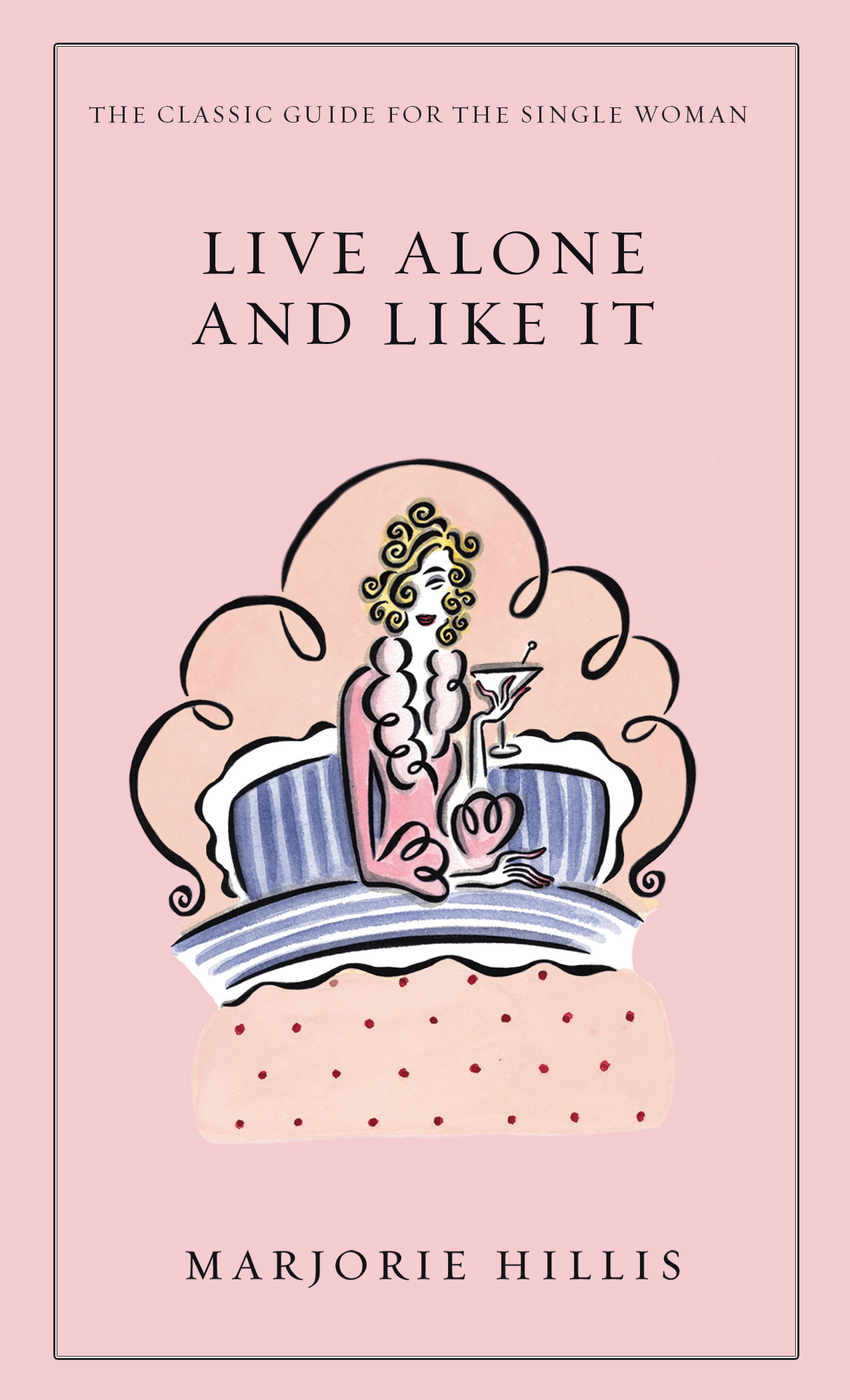

Hillis became the first mainstream American writer to concern herself with the specific happiness of single women, when in 1936, middle-aged and unmarried, she used the model of her own life to create a quietly radical self-help philosophy. Live Alone and Like It, her surprise bestseller, urged spinsters, divorcées, widows and old maids to throw off the disparaging nicknames and grudging charity of their families, and remake themselves as chic, independent “Live-Aloners,” who made their own choices, mixed their own cocktails and didn’t give a hoot what anyone else had to say about it.

The 1930s were a boom era for self-help in America. The ongoing Depression and dire political situation in Europe meant that readers wanted and needed to hear that success was possible and that things would be all right. Writers like Napoleon Hill (Think and Grow Rich!) and Dale Carnegie (How to Win Friends and Influence People) convinced their readers that they could triumph over the economy’s fearfully stacked odds if they learned to greet the world with a smile and a positive mental attitude. In 1937, TIME reported that Live Alone and Like It had sold over 100,000 copies within two months of its release. Hillis embraced her sudden fame and her role as the full-time Live-Alone guru, traveling the country giving talks and interviews about her glamorous independence.

It had been a long time coming. Born in Peoria, Ill., in 1889, Hillis moved with her family to Brooklyn at the age of ten, just after the city was absorbed into the greater metropolis of New York. Her father was head of the prestigious Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights, and her mother a conventional Victorian wife, who in 1911 published a book warning self-reliant modern girls that they would find true fulfillment only in marriage.

For a while it looked as though Hillis would have to tread an equally conventional path as an unmarried daughter, devoting her life to the care of her aging parents. But in 1929, the year she turned 40, the national crisis of the Wall Street Crash was overshadowed by personal loss, as both her parents died within a year of one another. Her siblings were married with children, and as the Depression decade dawned, Hillis found herself painfully lonely. The only constants were her job at Vogue, which she had refused to give up, and New York City. She packed up her family’s suburban house and fled back to the reeling city, to build a new life alone.

Hillis followed up her debut with Orchids on Your Budget, a guide to frugal yet fashionable living, then Corned Beef and Caviar for the Live-Aloner, a co-authored collection of recipes for the solo hostess. In 1939, New York: Fair or No Fair offered advice to unchaperoned women visiting New York for the World’s Fair.

That same year, the professional spinster made headlines when she married a wealthy widower named Thomas Roulston, in what looked like an admission of defeat and a betrayal of her faithful readers. But Hillis had never rejected marriage outright: her very first line of her book stressed that it was “no brief in favor of living alone.” She simply argued that a solitary state was likely, “even if only now and then between husbands,” and ought to be enjoyed. Ten years later, she’d learn the painful truth of those breezy words, when her older husband died of a sudden heart attack. Once again, Hillis packed up and returned to Manhattan. You Can Start All Over, she told older and wiser Live-Aloners in 1953, then a few years later, Keep Going and Like It. Being young, free and single was very different from being divorced, widowed and alone in midlife. But her message remained consistent: women had to declare and fight for their independence throughout their lives.

On Nov. 22, 1971, TIME reported the death of Marjorie Hillis at the age of 82, identifying her as a writer who “glorified spinsterhood.” But more than that, she had glorified living exactly as you chose, exhorting her readers to “be a Communist, be a stamp collector, or a Ladies’ Aid worker, if you must, but for heaven’s sake be something!”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com