Last summer marked a landmark moment for the gay rights movement in the U.S.: the legalization of same sex marriage. Crowds celebrated on the White House steps, rainbow-tinted profiles exploded across Facebook and thousands of marriage ceremonies in the following months lauded the cultural victory for LGBTs in America. But nearly 9,000 miles away, acceptance remains a mere ideal.

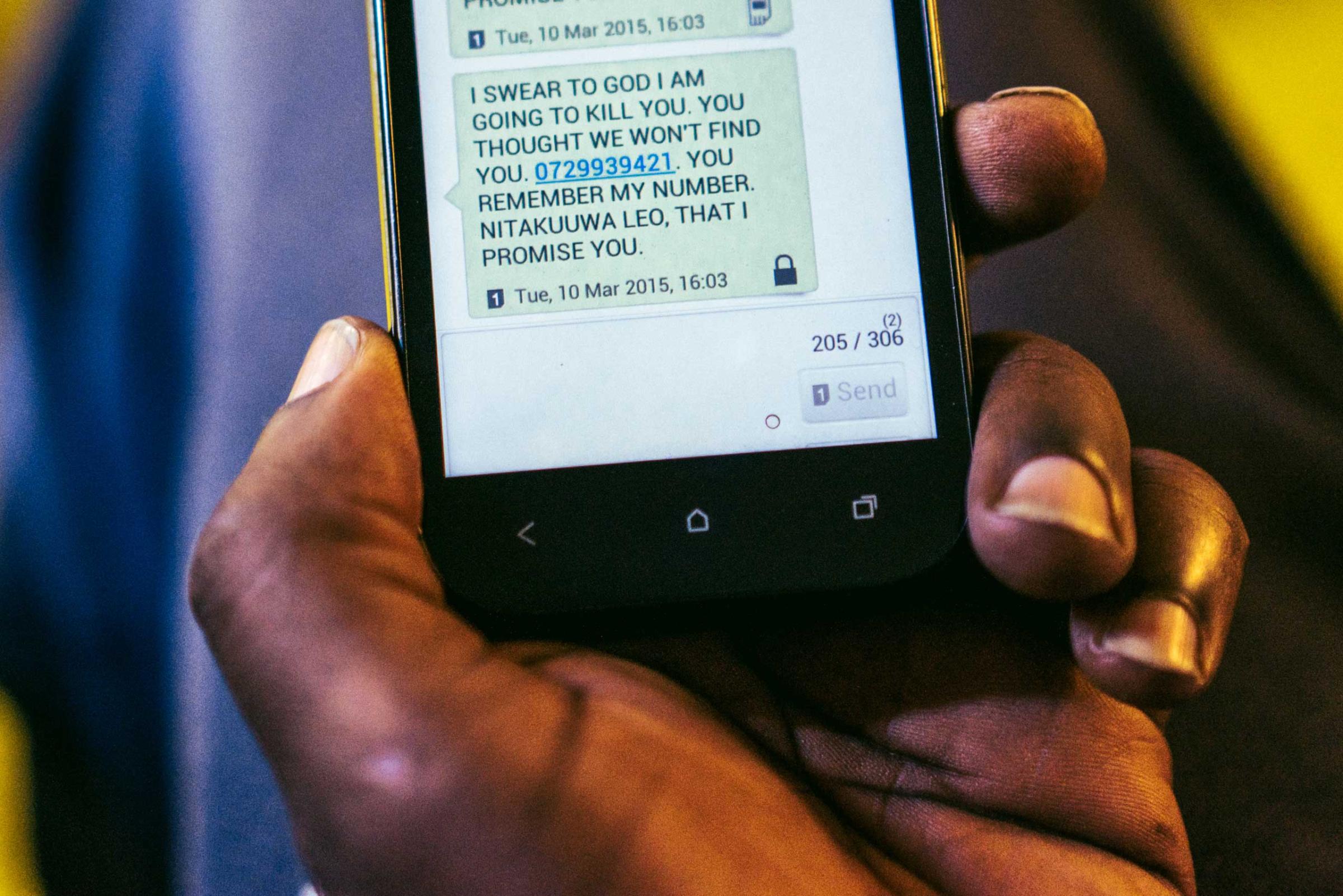

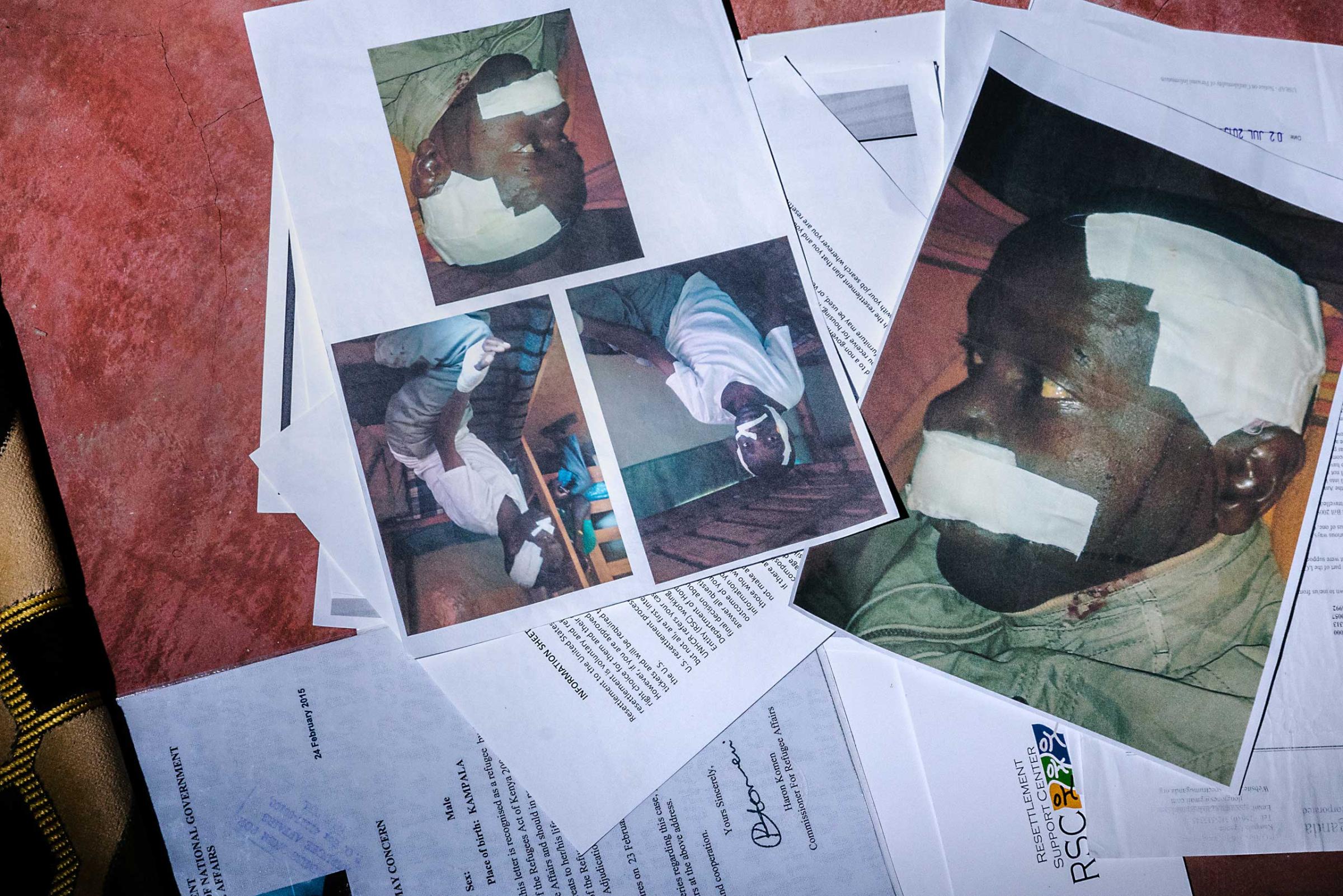

Photographer Jake Naughton, who worked last year with Kenya-based journalist Jacob Kushner, has documented LGBT refugees from East Africa, where leaders are imposing harsher laws on gays and lesbians. They have experienced beatings, torture, public humiliation, extortion, family disownment and sexual abuse. Some have been outed in their high schools, others labeled as terrorists and even put behind bars. Hundreds of them seek a new life in the west, fleeing to Kenya to wait in a refugee camp, Kakuma, for asylum or resettlement abroad—in Europe, Canada, or the U.S. That is, after a long and dangerous wait.

“It can take years, sometimes decades, to be granted asylum to leave Africa,” Naughton tells TIME. “They flee to Kenya, expecting some sense of safety, or at least the ability to securely wait out their processing time when in fact, they walked into the same nightmare.”

Gay equality has a long way to go in Africa. Nearly 90% of the Kenyan population believe homosexuality should not be accepted, according to a 2013 survey by the Pew Research Center. Of the continent’s 54 countries, only one, South Africa, has legalized same-sex marriage. While Kenya is known to be more liberal to gays and lesbians, homophobia remains rampant throughout the country, amid a rising Evangelical movement. In 2011, President Barack Obama called for expedited resettlement of LGBT refugees, but as Congress allocated little funding for the new legislation, agencies, churches, charities and NGOs that wish to help lack the resources to do so.

Naughton’s pictures depict the living conditions in Kakuma. While the UNHCR covers lodging and offers healthcare access to refugees, living conditions are destitute. “It’s extremely hot, very dusty, with 182,000 people packed into the camp,” Naughton says. “It’s huge, it’s sprawling and it was never designed to hold that many people.”

The photos, taken with a strobe flash, cast an intense light on each refugee. “The light is so bright and so direct, it mimics the intense scrutiny that all these people are under,” he says. “But then by its nature, it casts these deep shadows, which is kind of where the refugees find themselves confined to.”

The refugees’ scars are physical reminders that a new life abroad is worth waiting for: One man poses, a smile thrown off-kilter by a jagged scar from a seven-man machete attack in his apartment after seen with his boyfriend; a woman holds her arm out, showing a deep scar from shoulder to elbow, the fallout of an attack after giving an interview a few years ago on BBC radio.

“As a gay person who came of age after the worst of the experience of the LGBT community here in the U.S., I always felt disconnected from the stories that my mom told me about what my gay uncle experienced,” Naughton says. “But in Kenya, I witnessed that. [It was] amazing to see the way the community came together and supported each other in the face of horrifying violence and hardship and abuse.”

The images are the first part of what Naughton and Kushner envision as a three-part project that follows refugees from beginning to end: from Uganda, where they came from; to Kenya, where they fled to; to the U.S., where two have resettled. “It is our hope to create a record of the experience of the LGBTs that is underreported and unsung,” Naughton says.

Jake Naughton is a photographer with is interested in the intersection of LGBT and immigration issues. He is a frequent contributor to The New York Times, and his work has appeared in Al Jazeera America, Newsweek and the Atlantic.

Rachel Lowry is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com