This post is in partnership with the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin. A version of the article below was originally published on the Ransom Center’s Cultural Compass blog.

Twenty years ago, in February of 1996, Little, Brown and Company published David Foster Wallace’s (1962–2008) novel Infinite Jest. It was a bold undertaking for the firm to publish a complex, challenging novel that spans over 1,000 pages and contains hundreds of endnotes, many quite lengthy and all printed in very small type. The sheer size of the book required that it be sold for $30, an unorthodox price for any novel, let alone a second novel by a young, up-and-coming author.

Wallace began seriously writing Infinite Jest in 1991. The publication of the book took years of hard work not only from Wallace but from his agent Bonnie Nadell, his editor Michael Pietsch, and others who read and supported the book’s development in one way or another. Evidence of this hard work can be found throughout David Foster Wallace’s archive and in other related collections at the Harry Ransom Center.

Forming the foundation of these materials are the drafts of the novel, both handwritten and typed, that fill eight archival document boxes. Many draft pages are densely written in Wallace’s small, blocky print, often with revealing notes scrawled in the margins. On one page, for example, Wallace’s marginal notes offer his perspective on two characters central to the novel: Jim and Avril Incandenza. He writes of Jim Incandenza, an optics expert who founded a competitive tennis academy and later became an avant-garde filmmaker: “Jim had a hole in his soul… Why his suicide? He can’t survive success at film, much less perfection.” He writes of Avril Incandenza, the obsessive, workaholic, maternal head of the Incandenza family: “Mother uncaring of anything besides her view of herself as good mother… Uncaring. Jim cares, but is so locked inside himself he cannot show it, except obliquely, as over abstract art.”

While working on the novel, Wallace shared his early drafts with his editor, Michael Pietsch. Pietsch read and reread the manuscripts diligently, offering astute advice that helped tighten and clarify the narrative. Pietsch was encouraging but also practical. In a letter he wrote to Wallace on June 10, 1993, he voiced concern about the book’s length: “This should not be a $30 novel so thick readers feel they have to clear their calendars for a month before they can buy it.” Yet it’s apparent that Pietsch found the novel deeply moving and compelling. In a later letter to Wallace, the editor noted, “publishing this novel has probably been the most satisfying and exciting work I’ve ever gotten to do.”

Wallace also shared an early draft of the book with Don DeLillo, an author he admired greatly. A common friend told Wallace that the lengthy manuscript made an explosive sound when it landed on DeLillo’s front stoop. The two writers corresponded regularly during this period, and Wallace’s letters frankly reveal many of his struggles and concerns about the novel. In a letter dated October 10, 1995, Wallace wrote, “I think IJ is less self-indulgent and show-offy than anything I’d done before it… I think my fiction is better than it was, but writing is also less Fun than it was. I have a lot of dread and terror and inadequacy-shit, now, when I’m trying to write.”

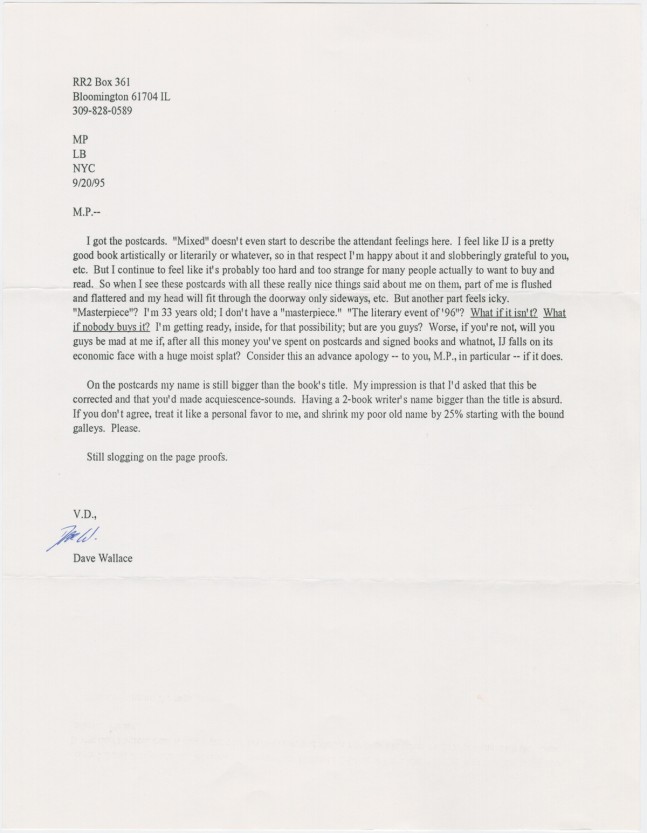

As the book came closer to publication, Wallace struggled with anxieties about how it would be received. The book was heavily promoted and highly anticipated, and although the hype must have been exciting and gratifying for Wallace, it was also deeply unsettling. When the book was touted by Little, Brown as a masterpiece before it was even published, Wallace wrote to Pietsch, “‘Masterpiece’? I’m 33 years old; I don’t have a ‘masterpiece.’ ‘The literary event of ‘96’? What if it isn’t? What if nobody buys it? I’m getting ready, inside, for that possibility; but are you guys?”

In tireless support of Wallace throughout the creation of this book was his stalwart literary agent, Bonnie Nadell. Just one example of her strong advocacy for Wallace can be seen in a letter she wrote to Little, Brown and Company on November 3, 1995, requesting that the publishing house rethink its plan to host the book’s launch party at a “hip, downtown” club. She noted, “David’s novel is not a hip, downtown kind of book. It is, we hope and believe, a major literary novel… I think the party should be held in midtown at a place where any major literary novel would be celebrated rather than a club which connotes young and ‘cool’.”

These items—and countless others in the papers of David Foster Wallace, Don DeLillo, Little, Brown and Company, and Bonnie Nadell, all housed at the Ransom Center—offer some sense of the struggles and the great joy that surrounded the writing, editing, and publication of one of the most defining books of the twentieth century.

To commemorate the twentieth anniversary of Infinite Jest, Little, Brown and Company is publishing a new edition of the novel on February 23, featuring a cover designed by a fan and selected by the publisher through an open contest.

Read more about David Foster Wallace and Infinite Jest at the Ransom Center’s Cultural Compass blog.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com