Considering the flashing lights and neoprene suits that are sure to be crucial to Monday night’s season finale of The Biggest Loser, one might be tempted to think that the glitz of a national weight-loss competition is a phenomenon of the reality television age. But such an assumption underestimates the timeless American passion for dieting.

Throughout the 18th and early 19th century, eating fads swept the country—from fasting to aggressive vegetarianism, and from idolizing Salisbury steak to chewing one’s food into oblivion as advised by the Great Masticator Horace Fletcher. It wasn’t until the First World War that the idea of a calorie-counting “diet” as we know and loathe it today emerged. Faced with wartime shortages at home and starvation amongst its Allies in Europe, the United States government needed an efficient way to organize and advise American food consumption. In came the calorie and nutrition science, concepts which had been bouncing around scientific circles and food reformers’ pamphlets for decades, but had yet to inundate the hearts and stomachs of the eating public. In its official messages about proper consumption during the war, the U.S. government introduced its citizens to the importance of the “scientific diet,” which popular publications readily turned into a novel method to help fashionable women “reduce.”

At first, these ideas were hard for the general public to swallow. During the war years, people often wrote to the government asking if “calories” were a new type of breakfast cereal or a novel explosive developed by the military. By the end of the 1920s, however, a new slim aesthetic was en vogue for women. At the same time, chronic diseases like heart disease and cancer had surpassed infectious disease as the leading cause of death for Americans, driving many to aim for a healthier lifestyle. By the 1930s, with the country now fanatical about this new science of nutrition, Fortune magazine declared that, “it is the gourmet who is a curiosity, the dietician who is a prophet.”

Over the course of a decade, weight loss had become a topic of public importance. By the early 1930s, magazines such as TIME were regularly printing updates on the weight-loss successes and failures of the country’s favorite public figures, including changes to President Roosevelt’s breakfast portions and the phenomenal shrinkage of artist Diego Rivera, who successfully lost 125 lbs. “in eight months by substituting thyroid extract for exercise.”

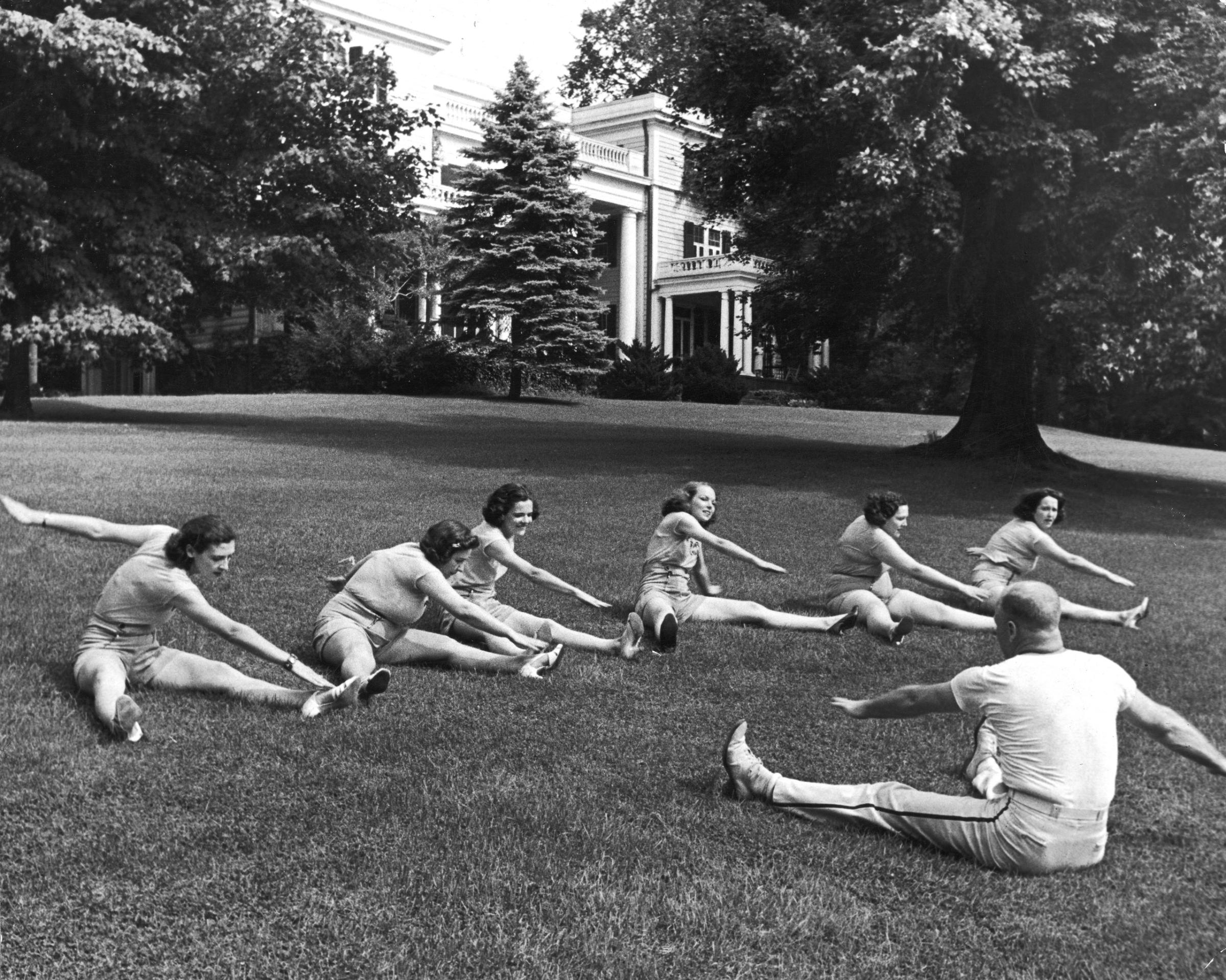

One of the savviest media men in American history, famed newspaper owner William Randolph Hearst, saw potential in the calorie-crazy nation and ran with it. Partnering up with the Chicago Board of Health, in 1934 Hearst’s Chicago Herald & Examiner sponsored a widely publicized “Diet Derby,” which followed the weight-loss journeys of three Chicago women over the course of 30 days. The contestants were Deon Craddock (140 pounds), Alice Joy (144 pounds) and Felicia Terry (165 pounds), all chosen, according to TIME, “because their chunky thighs and beefy arms would photograph well.”

When Shedding a Few Pounds Meant Reaching for Some Milk

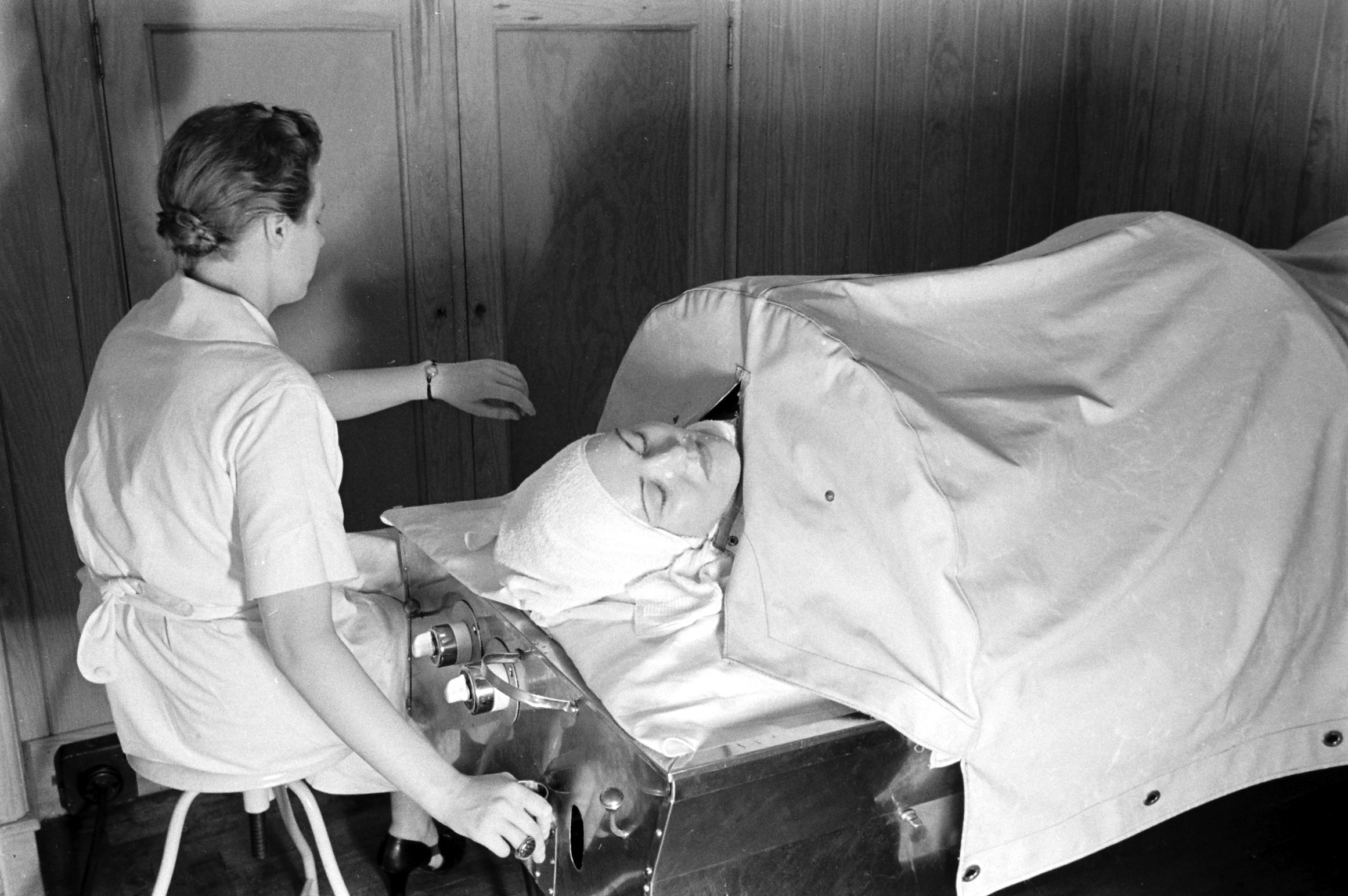

The goal of the affair was for each girl to lose a seemingly impossible “2 pounds daily.” In order to ensure the contestants shrunk rapidly, each participant’s reduction regimen was carefully monitored by the colorful Health Commissioner of the City, Dr. Herman Niels Bundesen, a bombastic man who famously helped reduced Chicago’s infant mortality rates and incidence of Syphilis.

At the center of the derby’s diets: lots of bananas. In fact, Miss Joy’s diet consisted entirely of six bananas and three or four glasses of skim milk daily. This regimen, the physicians warned, “should not be attempted unless under medical guidance.” Miss Terry’s diet was less strict, generously allowing for spinach at lunch and liver at dinner in addition to the bananas and milk. Miss Craddock’s was the most diverse: toast for breakfast; salad and soup for lunch; beef, bread and vegetables for dinner.

Unsurprisingly, the woman who only ate bananas and milk took the early lead in the weight loss competition and held out strong for the entirety of the 30 days. But for all the women at the end of the competition, as reported by the New York Times, “a new sparkle in their eyes and a flush to their cheeks attested that while they had lost weight, they gained in appearance, health, energy and spirit.”

This “Diet Derby” and the national attention it received gave Dr. Bundesen a perfect platform by which to advocate for this particular facet of public health. “It is perfectly possible for any one to do as these girls have done,” the Commissioner advised. “Remember that every pound lost is health gained, beauty added.”

From Hearst’s original Diet Derby, the concept of the publicized weight-loss competition reverberated across the nation for decades, with later contests sponsored by other papers and private corporations. President Truman even had a miniature “Derby” of his own with his staff at the White House in 1949, sparked by the fact that one day the President realized that “he could not see around [his] hefty aides.” So it wasn’t that much of a departure to bring a weight-loss contest to the screen. Before long, there were excruciating exercise regimens, yelling trainers and a $250,000 cash prize for the winner. For her victory in Mr. Hearst’s Diet Derby, Miss Joy probably only came away with a hatred for bananas.

Emelyn Rude is a food historian and the author of Tastes Like Chicken, available in August of 2016.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com