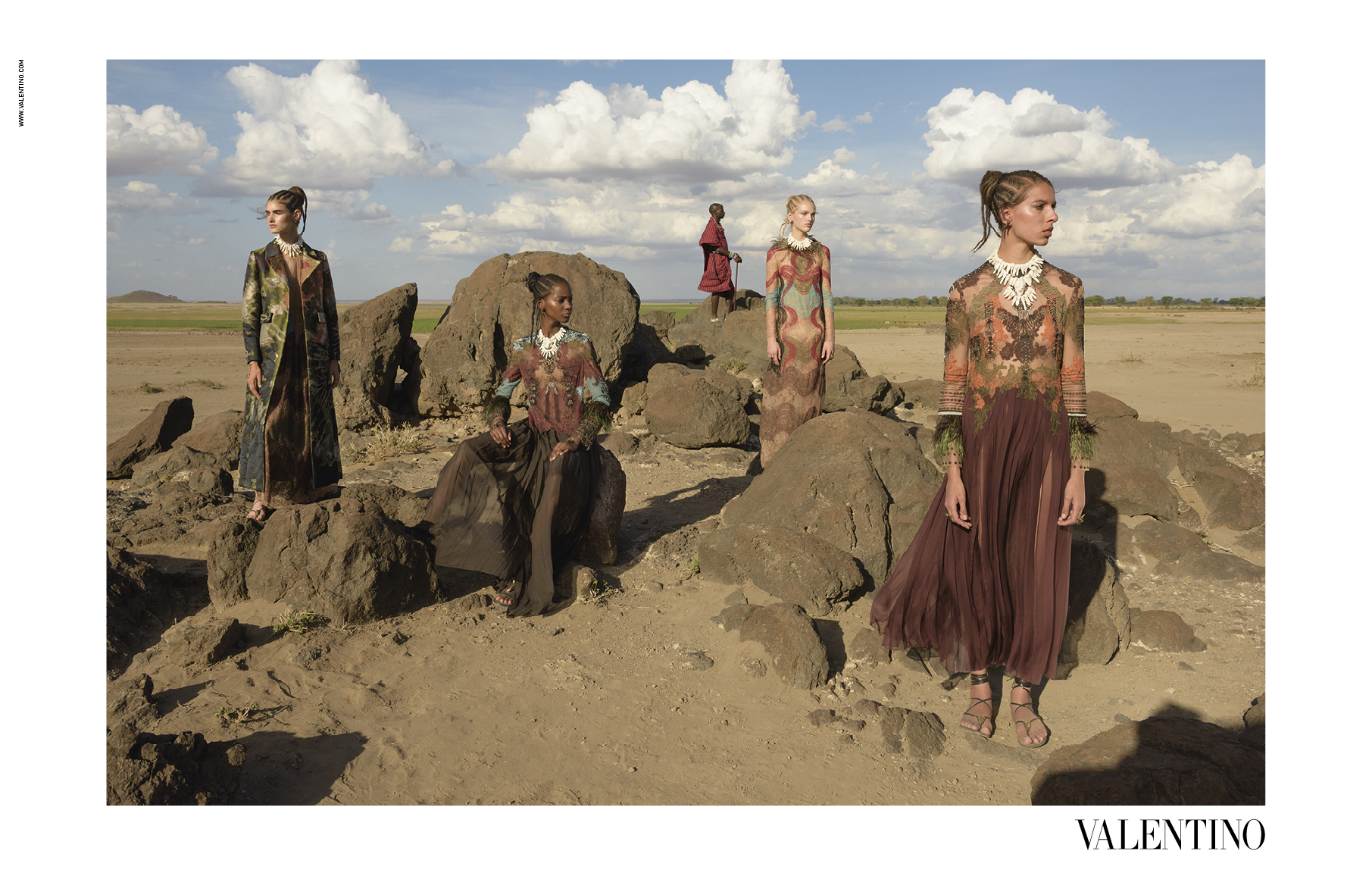

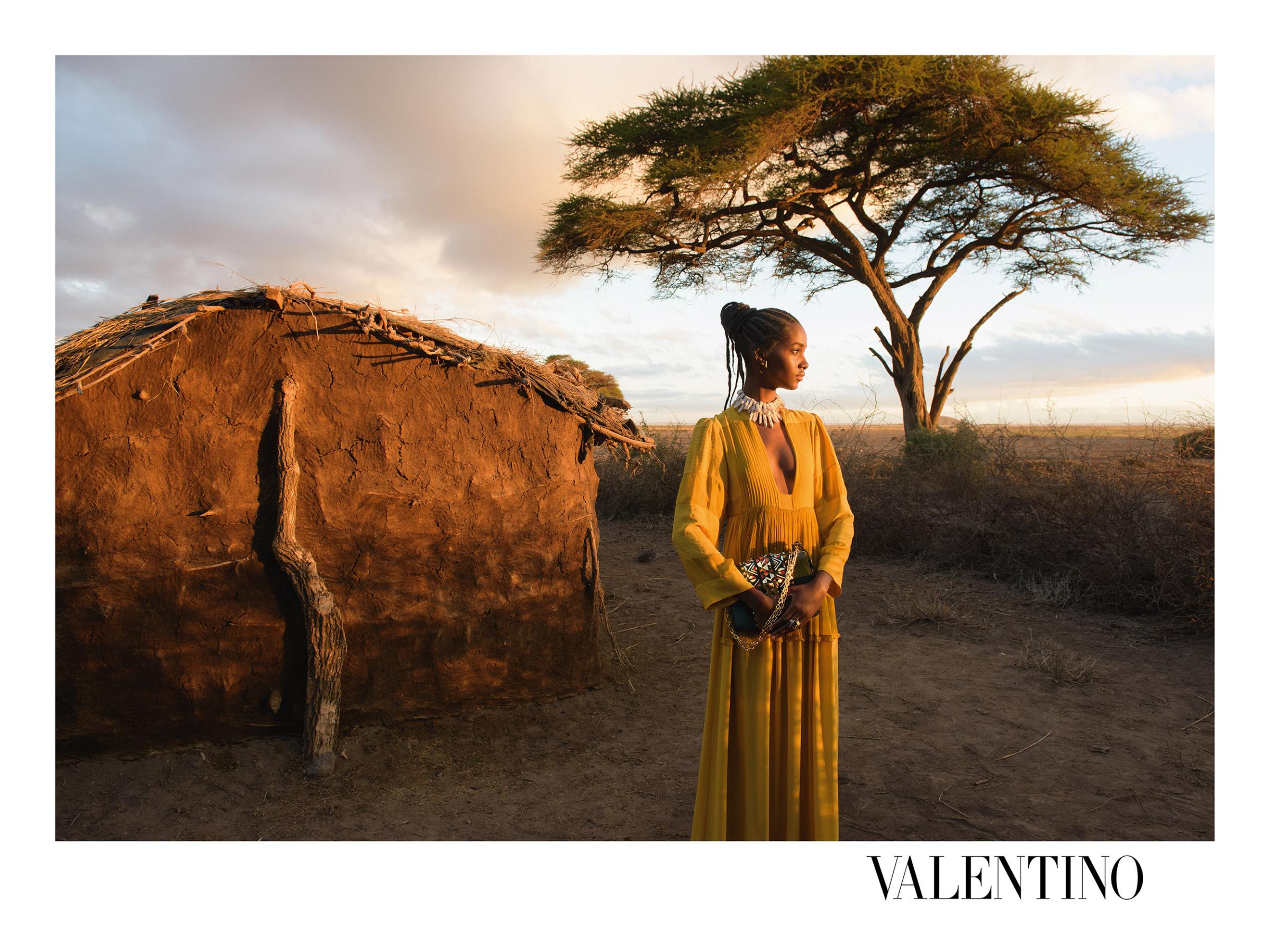

Valentino’s Spring/Summer 2016 women’s ready-to-wear collection, unveiled last October, references African culture, sporting prints and motifs commonly seen across the continent. So when the fashion house looked to create the collection’s visual campaign, the co-creative directors Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli called upon photographer Steve McCurry, who has made his reputation, over more than 30 years, documenting ancient cultures and traditions.

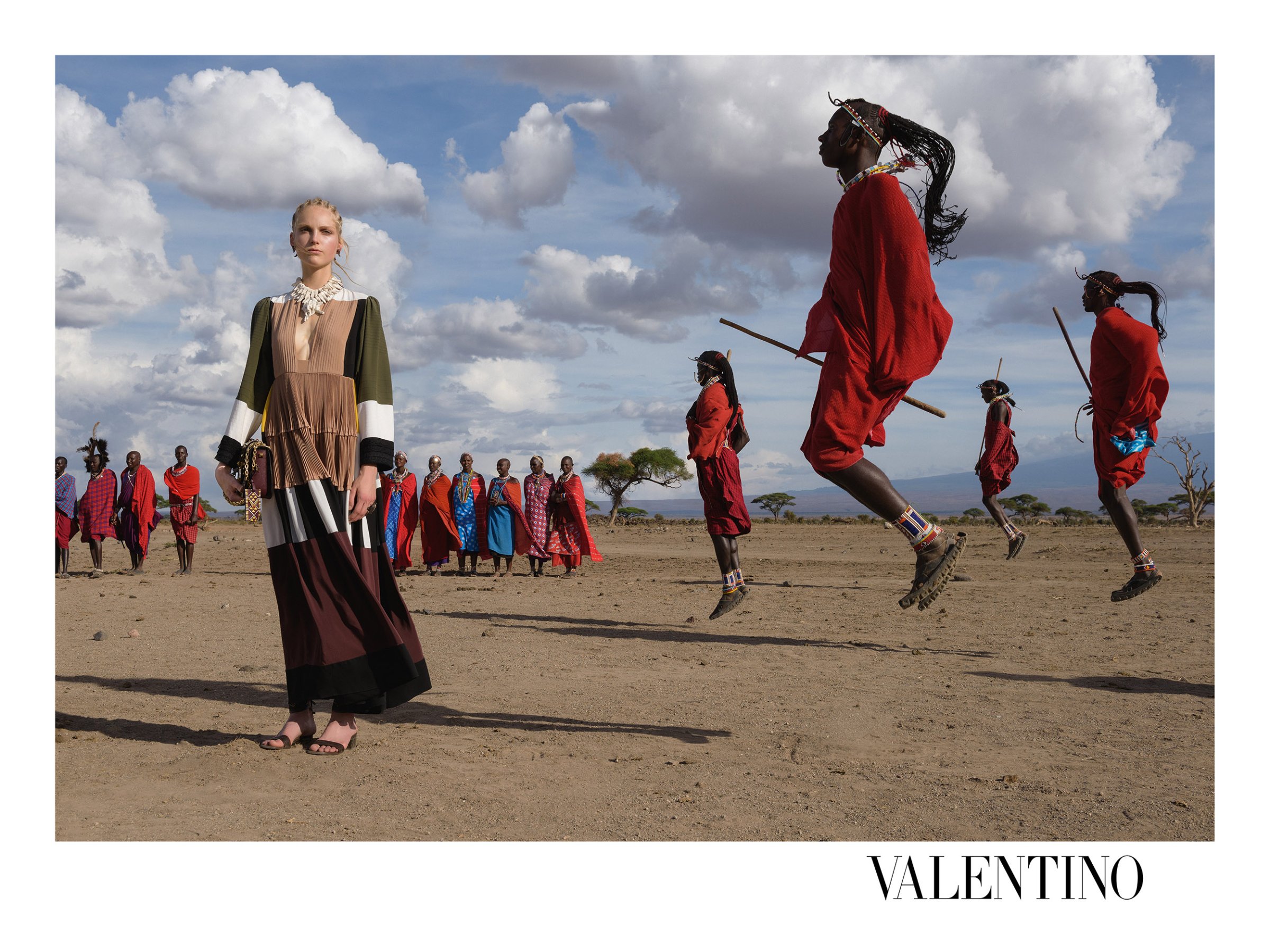

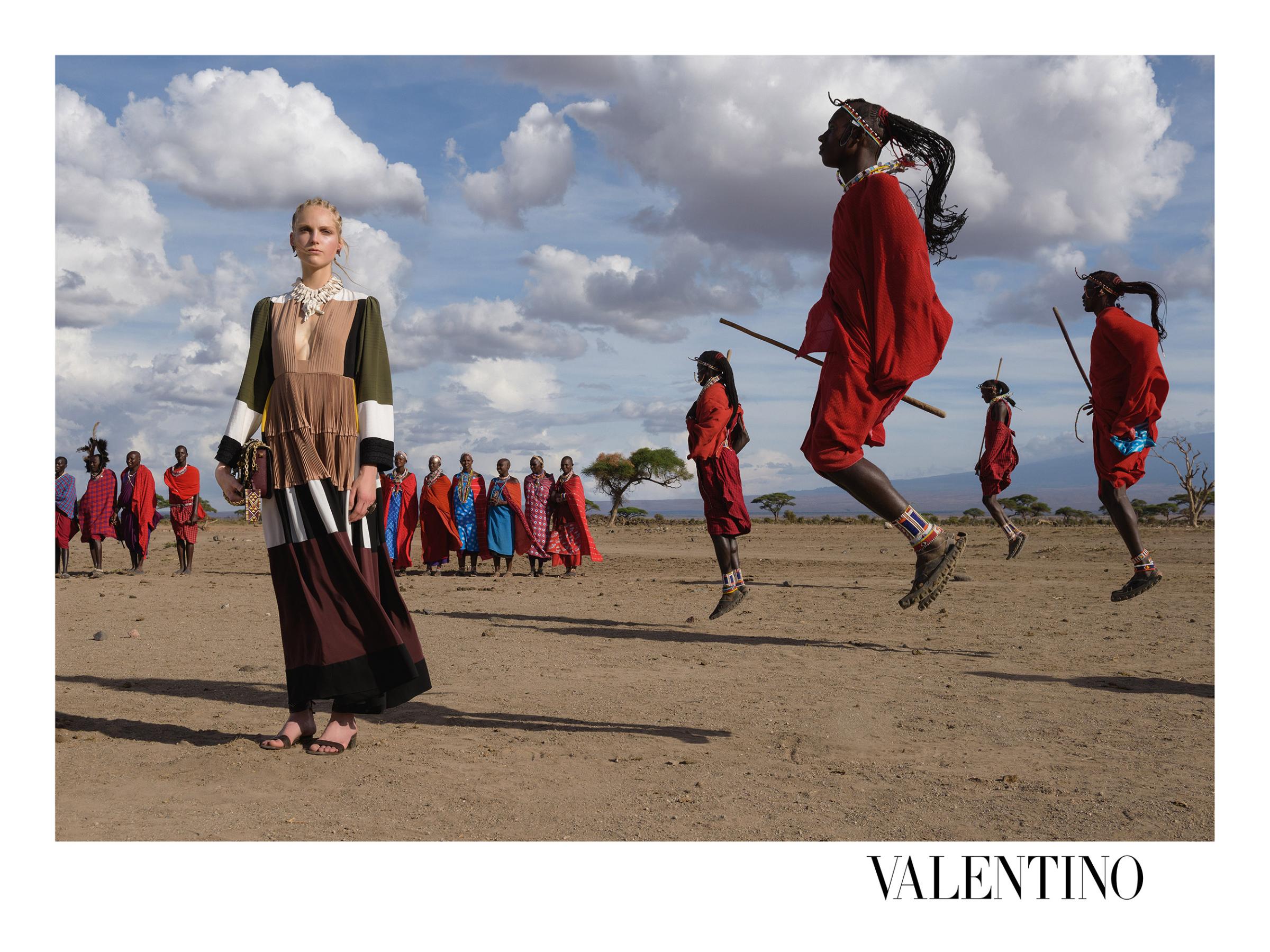

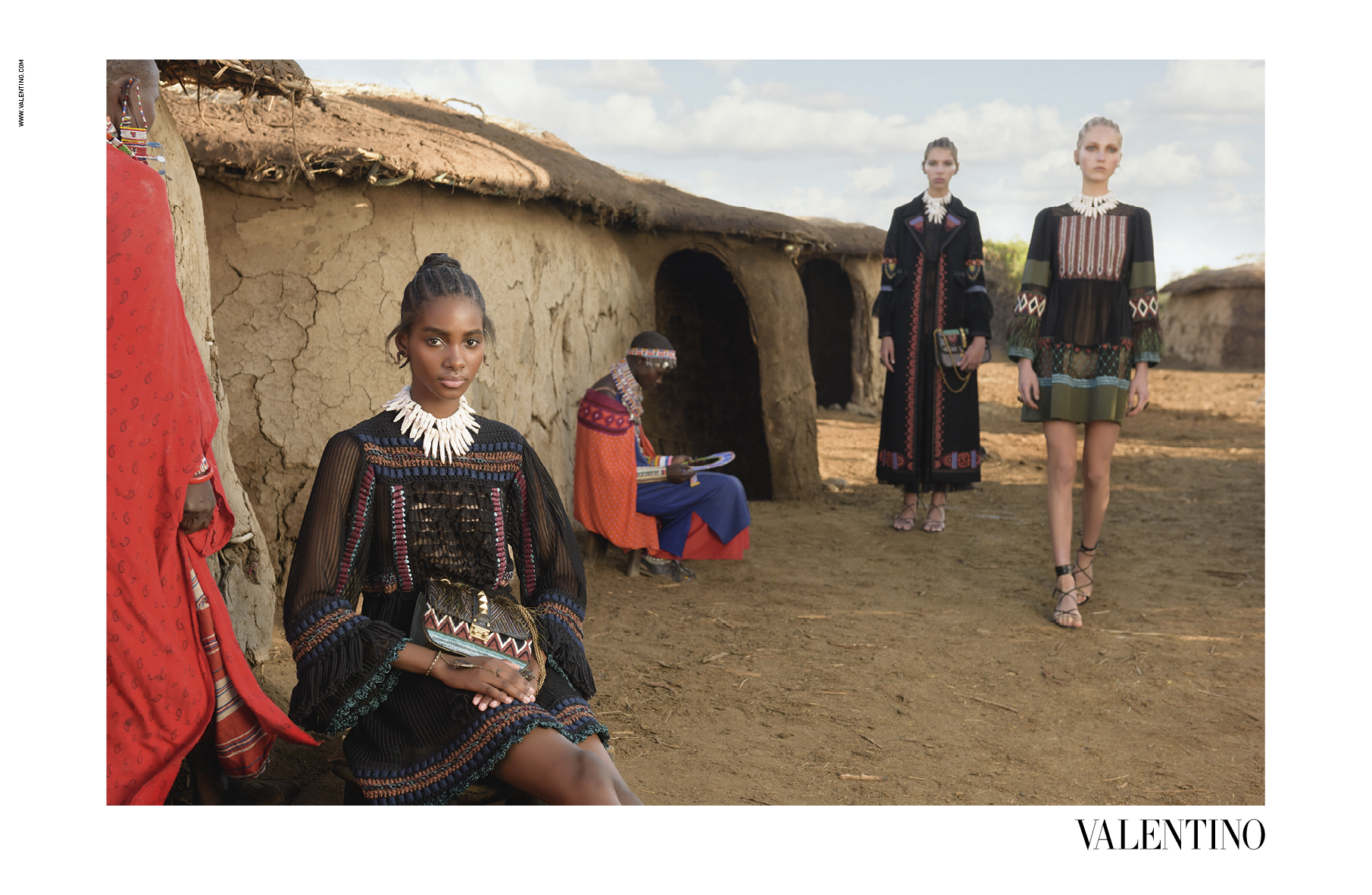

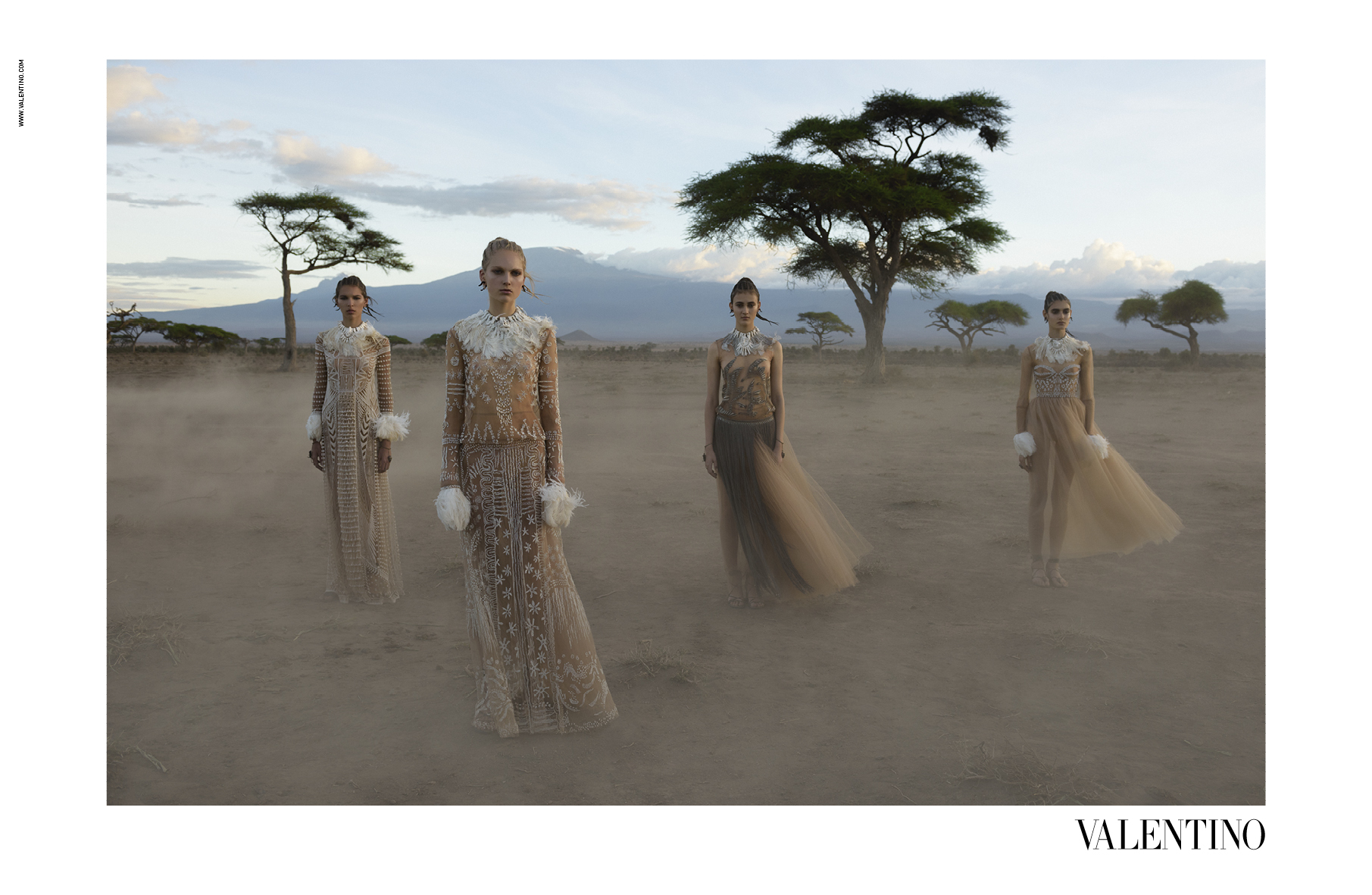

The campaign, which was shot over three days last November and first appeared in the February issue of W magazine, was set against the backdrop of Amboseli National Park in Kenya and included local Maasai people.

McCurry, whose repertoire of commercial assignments includes a 2011 Louis Vuitton campaign and the 2013 Pirelli Calendar, says he is solicited for commercial jobs “now and then.” His rationale for taking on this assignment was clear: “It’s always fun to work with the best people on the best projects,” he tells TIME. “This is one of the top fashion houses in the world.”

Location is usually a key factor for the photographer. “It’s one of the great locations in the world,” he says of Amboseli, “and you have the Maasai, which are amazing people.”

Fashion photography and photojournalism are seemingly at odds, not only for the content but also the practice. Most photojournalists travel alone on assignment, potentially with the help of a guide or translator, but a fashion shoot is “a different animal,” as McCurry puts it, with a large crew involving models, hair and makeup artists and wardrobe stylists. He described the experience as both challenging and stimulating. “You’re presented with the models, the clothes, the location and you have to find a solution to make it work.”

But while the client is typically a guiding influence in the creative direction for ad campaigns, Chiuri and Piccioli handed the reins to McCurry to achieve a more authentic approach. “Our idea was to find not a fashion photographer but somebody that could help to tell a story,” Chirui tells TIME.

Their goal was to let pictures happen rather than construct a scene. They went out at 4am to wait for the light of dawn, an unusual concept in conventional fashion photography. They also referenced a human, natural element that they thought a documentary approach could lend, which, they believe, you usually don’t find in the fashion world.

At one point, the creative directors say, McCurry approached a group of Maasai who were singing and dancing. With their permission, he photographed a model in the foreground of their performance. “Every time I see the picture… I can hear them singing,” Piccioli says. “You hear the voices, you see them dancing. So it’s about life, it’s about different cultures mixing together.”

The collection, which debuted at Paris Fashion Week last October, sparked criticism on social media regarding perceived racial insensitivities. One commenter on Twitter wrote, “That’s very cute of #Valentino to pay homage to the African culture for the new collection, but ummm…where were the african models?” Another wrote, “Returned from my shower to find Valentino putting cornrows and dreadlocks in their white models’ hair.” Robin Givhan, a fashion critic at the Washington Post, tweeted “Well kids, we’re going to “wild, tribal Africa.” On Instagram, Valentino described the collection as “primitive, tribal, spiritual, yet regal.”

Chiuri says they were surprised by the blowback. “If I like something that is not part of my culture, but I like it, why can’t I use it?” she says. “If I do an African show, and I use only black girls… it’s also something that is not right.” Piccioli adds: “Multicultural beauty is something we were interested by” and the goal was to create “an idea of beauty which was mixed by different races, different references from different cultures.”

After the ad campaign was released, Fashionista criticized Valentino for “using people of non-European cultures as a backdrop for white models wearing European designers’ clothing.”

But Piccioli defends the photographs. “We wanted people to get the culture, to get the spirit, and to see that they have some dignity, not to shoot them as props,” he says.

For McCurry, the Maasai were accommodating and helpful. “They’re savvy, they have been able to find a way to retain their own culture and be true to their own traditions, and yet… be able to work with other people in the world,” he says. “If you want to visit them and spend time with them and photograph them, they understand the value of that, which I think is exactly the way it should be.”

He also referenced the longstanding tradition of cultural appropriation in art. “I think that whether you’re an artist or musician—I’m thinking of Paul Simon, he was inspired by African music, or Gauguin went to the South Pacific—I mean we all draw inspiration from life,” McCurry says. “Going somewhere and appreciating it and incorporating it into your art… I think that’s one of the great pleasures of experiencing different cultures.”

Marysa Greenawalt is a photo assistant at TIME and a contributor to LightBox. Follow her on Twitter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com