This piece is part of an ongoing series on the unsung women of history. Read more here.

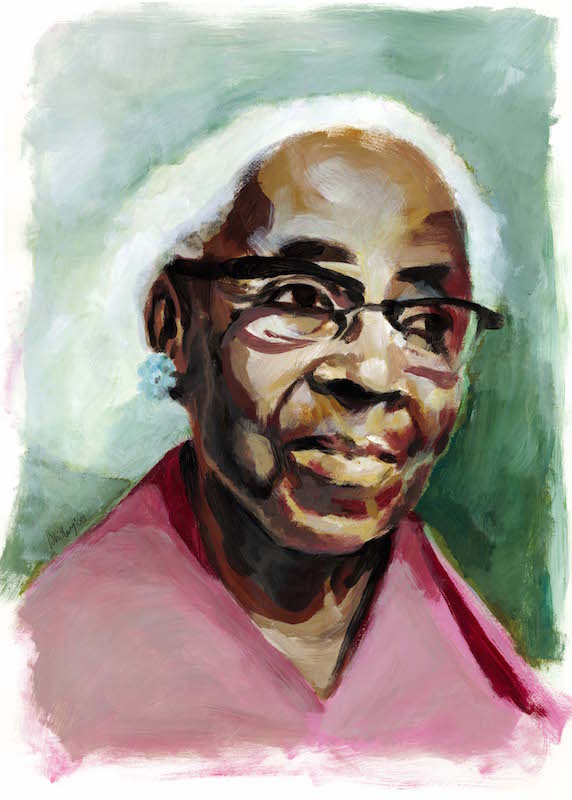

Who was the “queen mother” of the American Civil Rights movement? If you answered “Rosa Parks,” you’re wrong—a woman named Septima Poinsette Clark earned that moniker for her pioneering civil rights work years before Parks made her fateful ride. The daughter of a slave, Clark made her mark on the movement not in a bus or at a lunch counter, but in the classroom.

Born in Charleston, S.C., Clark was one of eight children. Her father, Peter Poinsette, was forced to serve as a messenger to Confederate troops as a young slave during the Civil War. After the war, he married Victoria, who grew up a free black in Haiti and resented her husband’s nonviolent attitude towards the racial repression of the postwar South. Both of them instilled their daughter with a love of education and made sacrifices on behalf of her schooling, so it made sense for Septima to become a teacher.

But when she got her teaching license, she realized she would not be able to teach any children—black or white—in her native Charleston. “Segregation was at its height,” she later recalled, and black teachers were barred from teaching any students in South Carolina’s capital. For a while, she taught on John’s Island outside of Charleston instead, but in 1919 she joined the NAACP and returned to her hometown. Emboldened, she went from door to door, collecting signatures of black parents who wanted their children educated by black teachers in Charleston schools. Eventually, two-thirds of the city’s black population signed the petition. A year later, Charleston’s ban on black teachers was overturned.

Clark could have settled into life as an elementary school teacher, but she kept pushing. Along with other NAACP members, she began to agitate for higher salaries for black teachers. It took her more than 20 years to help win equal pay for her colleagues, but in 1945 teacher pay was equalized.

As the NAACP began to rack up victories, pressure to declaw the organization mounted from whites who clung to the South’s Jim Crow policies. Clark was fired from her job in 1957 for refusing to renounce her membership in the NAACP under a law that forbade public employees to belong to the organization. At almost 60 years of age, Clark was ousted from the profession that was her vocation.

But Clark’s career was only just beginning. A few years before being fired, she had discovered a Tennessee school that featured integrated workshops on citizenship and civil rights. She began to teach literacy there, educating black students about citizenship laws and civil rights.

This commitment to educating her fellow black citizens came with a price: The state of Tennessee revoked the school’s charter, forcibly closed down its buildings and arrested teachers on bogus charges. Clark was accused of illegal alcohol possession and arrested, though the charges were later dropped. When she was released from jail, Clark was invited to continue her work in Georgia by none other than Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The “Citizenship School” model she started became a juggernaut. It helped fill educational gaps left by segregated school systems that made black students the last priority.

The classes Clark established schooled thousands of students in basic literacy and civil rights, producing savvy new voters and changing the course of the Civil Rights movement. Among her mentees was Rosa Parks, who openly admired her patience and courage.

Though Clark’s work took place in the background—and was often minimized by male leaders in the movement—the fight for racial equality in the United States simply would not have been the same without one teacher bent on making the most of her hard-won education. “The greatest evil in our country today is not racism, but ignorance,” Clark wrote in 1965. By bringing education to the struggle for civil rights, Clark fought both.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com