Violence erupted in Hong Kong on Monday night after a municipal crackdown on outdoor food vendors rapidly escalated, with enraged protesters clashing with police overnight.

At least 300 people gathered in the streets, becoming increasingly violent as the night went on. Demonstrators hurled bottles and garbage cans at police officers and tore bricks from the pavement to be used as weapons. Police responded with pepper spray, and also reportedly fired warning shots into the air — an unprecedented gesture in Hong Kong, where political unrest typically veers toward the civil.

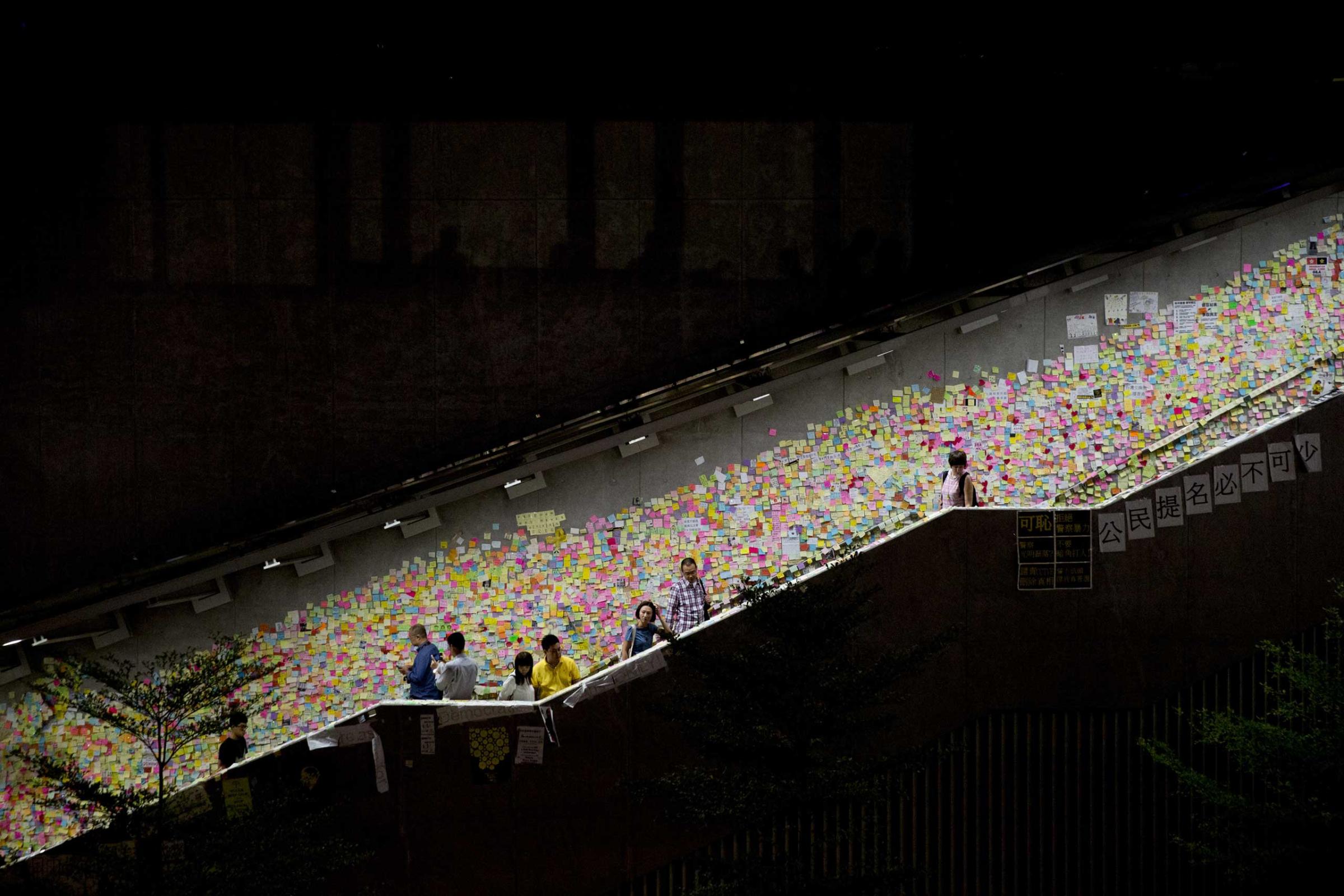

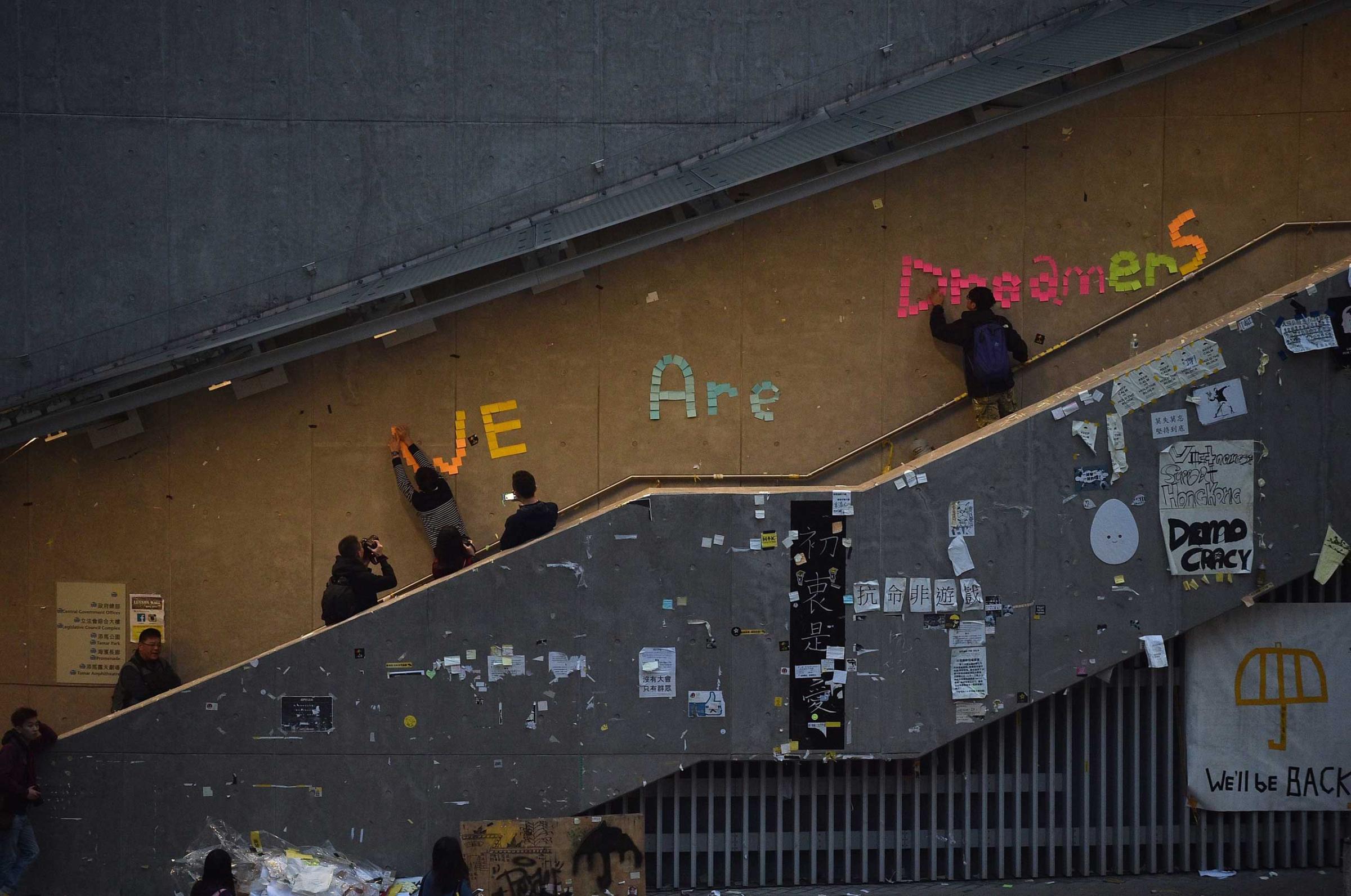

It was the most violent protest in the city since the pro-democracy demonstrations that floored Hong Kong during the fall of 2014. The South China Morning Post reported that 48 police officers and at least four journalists were injured as the conflict escalated into the early morning.

The protests erupted Monday evening in Mong Kok, a vibrant commercial neighborhood that was a crucible of unrest during the demonstrations that ended 15 months ago. The district is a popular venue for food hawkers, especially in early February, when locals and mainland Chinese tourists flock to the streets to celebrate the Lunar New Year.

Outdoor food vendors are a cultural staple in the city, but Hong Kong’s government has long been concerned with their potential threats to health and hygiene. On Monday — the first day of the Chinese New Year — hygiene officials planned a crackdown on food stalls in Mong Kok, prompting the fury of both the vendors and political activists who joined them in solidarity.

According to multiple reports, several of the protesters appeared to belong to groups representing Hong Kong’s so-called localism movement, an isolationist campaign that calls for complete independence for the territory from mainland China.

Photos circulating on social media showed one protester, a young woman, bloodied and on the ground, being held down by a police officer. 54 people were arrested, ranging in age from 17 to 70, Stephen Lo, Hong Kong’s police commissioner, told reporters on Tuesday afternoon.

“I was upstairs in my hotel room at around 2 a.m. when I heard bangs from the street — at first I thought it was fireworks, until I looked out the window,” one tourist, who requested anonymity, told TIME on Tuesday morning. “I’m jetlagged, so I wanted to go downstairs and grab some noodles, but I figured ‘no way.’”

Protesters insisted that the outrage over the crackdown on food vendors was warranted, and that the violence that ensued was precipitated by unjust police hostility. The relationship between the police and the public has gradually deteriorated since the beginning of the city’s pro-democracy movement dubbed the Umbrella Revolution, when police deployed tear gas to disperse protesters that had blocked several major thoroughfares. Since that movement — which lasted nearly three months – ended in December 2014, protests against everything from mainland Chinese shoppers to street musicians singing in Mandarin have taken place.

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

“During the Chinese New Year, the night markets in Hong Kong provide the public with cooked food and a place to spend the festive season, but since the current government took power, it has demanded ruthless cooperation from the food vendors,” Joshua Wong, the student activist who stood at the center of the 2014 demonstrations, tells TIME. “[Monday night’s protests] were caused by the inappropriate use of police force, which deliberately provoked public anger. It is shocking.”

Authorities see the situation differently, blaming the unrest on the anger of the mob.

“Radical elements have come with self-made weapons and shields and clashed with police,” Crusade Yau, a deputy district police commander in Mong Kok, told the South China Morning Post. “The situation ran out of control and became a riot.”

Yau confirmed to the Post that a member of the police force had fired two warning shots at the crowd around 2 a.m. local time.

By 8 a.m. Tuesday, the demonstrators had dispersed, though police in green fatigues and riot gear stood steadfast along the blockades on Nathan Road, a major thoroughfare on the Kowloon peninsula. The Mong Kok station of the MTR, Hong Kong’s metro system, was shuttered (to the anger of one expatriate, who screamed at a solemn police officer that it was “outrageous”). Street cleaners in yellow vests swept the garbage and smoldering ashes of the night before into piles on the sidewalk.

In a statement on their website, the Hong Kong Police Force urged the public to “exercise restraint” and “leave the scene as soon as possible,” as local media reported fires continuing to rage in the normally bustling neighborhood.

“Any acts endangering public order and public safety will not be tolerated,” the statement continued. “The public should express their views in a rational and peaceful manner.”

Willy Lam, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Centre for China Studies, describes the Monday and Tuesday events as emblematic of a larger, steadily expanding rift between the city’s government and the people it governs.

“It’s a continuation of the sentiments which had its first outbursts in the Umbrella Movement of late 2014,” Lam told TIME Tuesday. “There is massive dissatisfaction both economically and politically … they [Hong Kong citizens] are just unhappy with authority, the police, of course, being symbols of that authority,” he added.

Lam expressed concern that this week’s violence will only exacerbate the Chinese government’s increasing proclivity to stifle dissent in its freest territory.

China controls Hong Kong based on the “one country, two systems” principle, which promises the latter a high degree of autonomy and democratic rights not conferred on citizens of the communist-governed mainland. But recent events — such as the detention by Chinese authorities of five Hong Kong publishers — have lead to widespread fears that that autonomy is rapidly eroding.

“The importance or appeal of these nativist groups has been exaggerated by people, including Beijing, because this is a good excuse for them to crack down on genuine democratic expression in Hong Kong,” Lam said.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Rishi Iyengar/Hong Kong at rishi.iyengar@timeasia.com