Almost six months after thousands of foreign peacekeepers waded into Central African Republic in a bid to control the fallout from street fighting that left hundreds dead in the capital of Bangui, they remain unable to stem the killing and population shift that has begun to redefine its makeup.

Their arrival under a United Nations mandate forced a retreat by the disbanded militants of Séléka, the mainly Muslim rebel coalition that seized control earlier that year and began a campaign of looting and killing largely against non-Muslims. But that power void, exacerbated by a lax justice system, was quickly filled by anti-balaka. The groups of armed vigilantes, initially organized to combat local crime and whose ranks of Christians and animists includes ex-soldiers, have fought back against the militants and furiously targeted the Muslim minority, which they view as complicit in Séléka’s unpunished abuses.

Anti-balaka now stand accused of crimes worse than what prompted their retaliation as the burning of whole villages and gruesome mutilations, among other threats and attacks, have killed an untold number of people and pushed hundreds of thousands of others from their homes. Amid tales of ethnic cleansing in the west and as reports of crude attacks surface in the east, where Séléka remains in control and is regrouping, the country continues to slide into perhaps the bloodiest and most unstable crossroads of its independence.

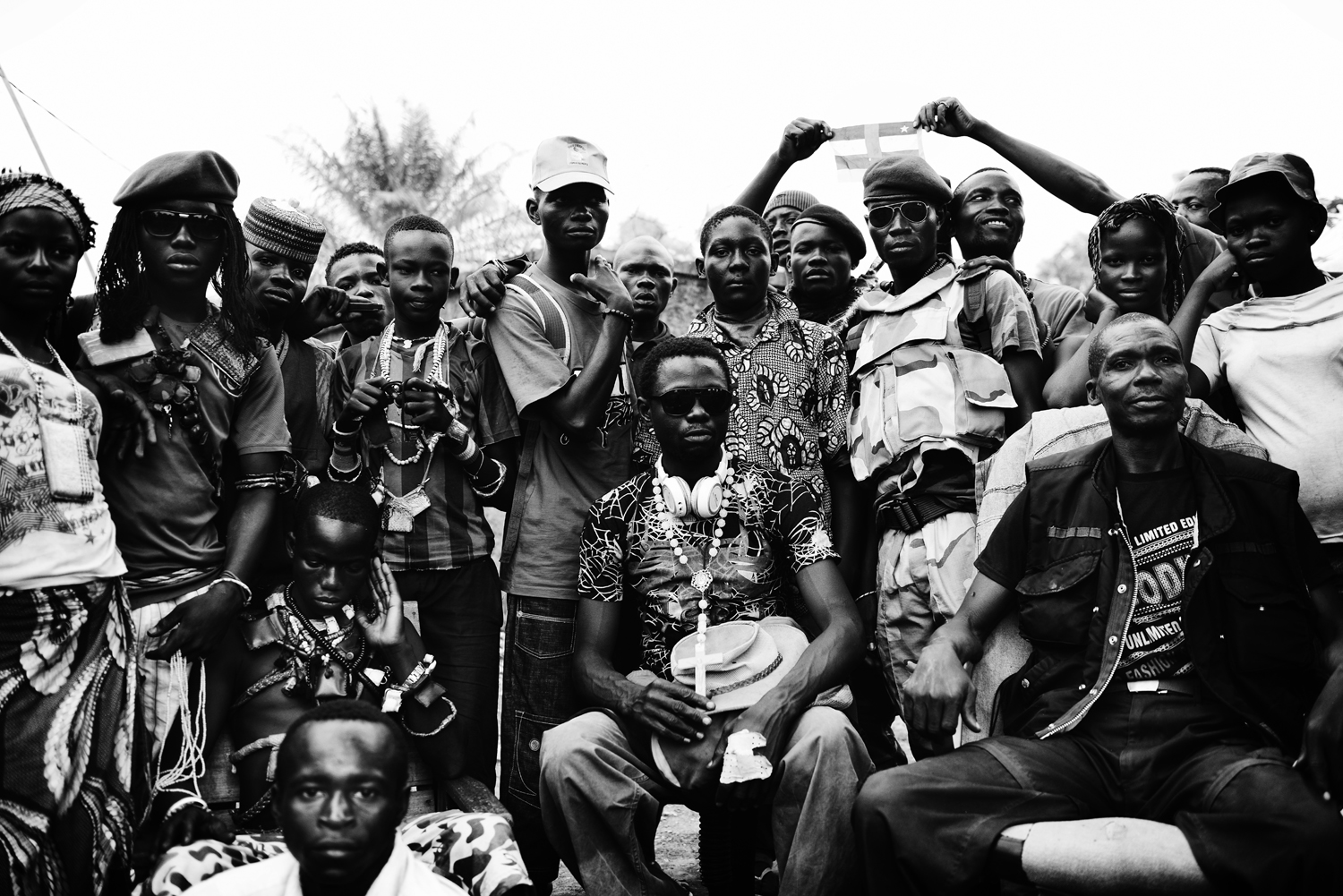

Italian photojournalist Ugo Lucio Borga, of the Echo Photo Agency, witnessed this turning point first-hand when he arrived in January. He took advantage of a connection with an army sergeant-turned-commander of a Bangui-based anti-balaka militia, who he met years ago in the remote southeast while covering the hunt for Joseph Kony, the elusive leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army. With prime access to their day-to-day happenings, he could document the conflict as anti-balaka became more brazen and learn more about the fighters beyond the amulets they wear as “protection.”

“They are really young people without education, without culture, but they needed to do something to stop the violence from the Séléka,” he told TIME. With most schools out of operation and seemingly few families who hadn’t seen bloodshed, he could see why they so easily took up arms. “Now the problem is that they know what war really means and they have become another people. They are now fighters.”

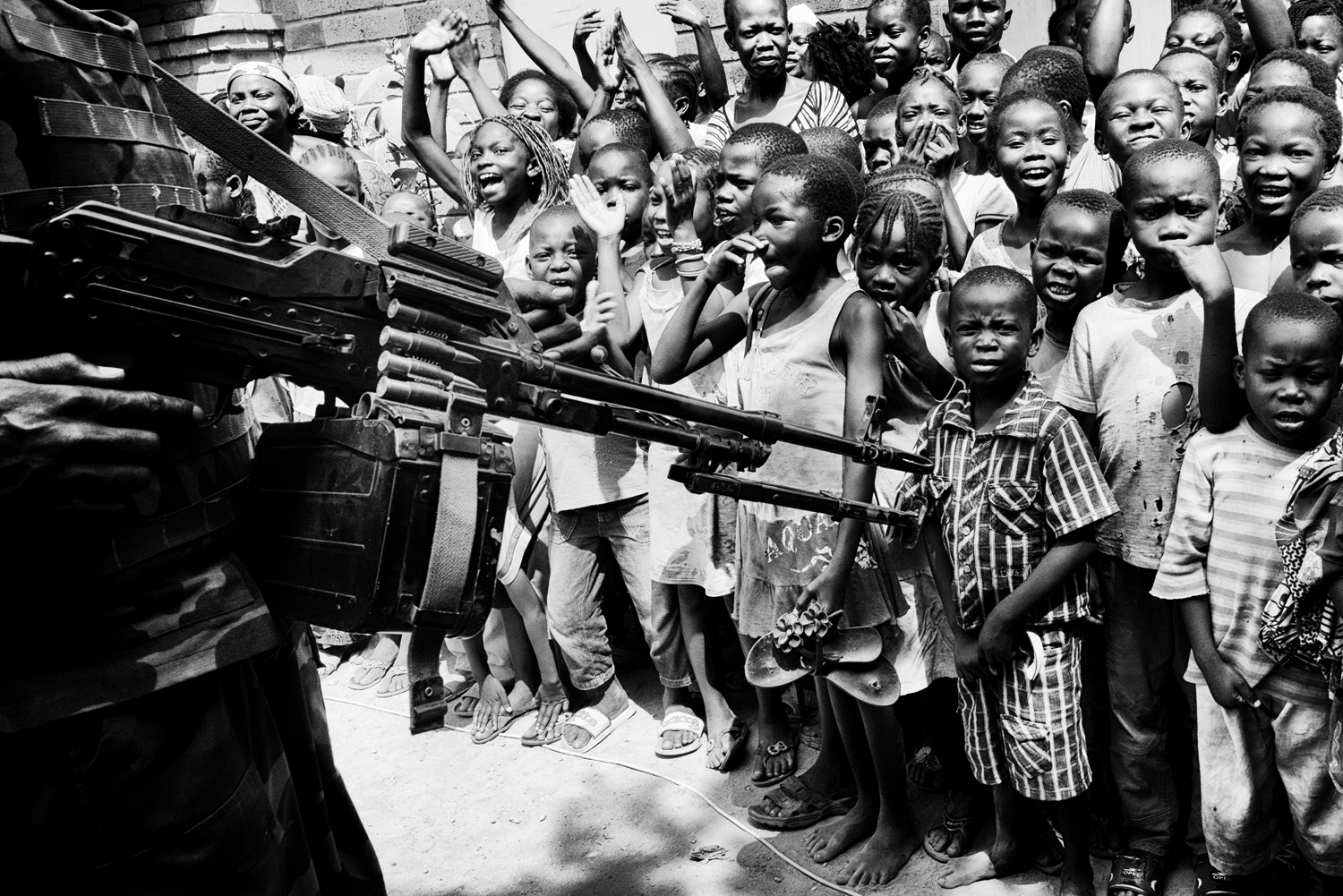

Throughout his trip, during which he also shadowed French troops and peacekeepers from Rwanda and Burundi, Borga saw the effect on children—“after one year of violence, continued violence, they consider the situation normal”—and became more aware of the roots of the conflict. The fighting, after decades of corruption and meddling by external influencers, appeared to take on a more religious undertone and sparked concerns of a partition in a country where Christians and Muslims have historically lived in peace, despite instances of marginalization. But Borga found that not all anti-balaka wanted to outright rid the country of its Muslims. This specific militia told him they targeted foreigners because, among other reasons, Séléka included militants from Chad and Sudan.

Borga left in February having captured a series of raw, intense scenes that stand out for their intimacy. He plans to return ahead of the elections, scheduled for February 2015, but knows that making a big influence is a tall order when the conflict is so neglected on the international stage. Still, it’s the ability to inform that drives him, as well as an innate curiosity as to how it will end: “I think it’s a question of humanity, if it exists somewhere.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com