Every four years, the ritual begins. Contenders from the Democratic and Republican parties descend on Iowa and New Hampshire. Voters declare their allegiances. And for many photographers, the return of campaign season is time to capture countless staged events in schools, diners and ball rooms. But what’s tradition for some is brand new for others.

As New Hampshire prepares to vote, TIME LightBox talked with three photographers who have recently embarked on their first presidential campaigns. Mark Abramson, Natalie Keyssar and Mark Kauzlarich offer three different visual approaches to the trail.

Mark Kauzlarich, freelancer and contributor to Reuters

“I think the hardest thing, and it’s something I don’t think I still have completely come to terms with, is understanding that you can’t get every photo,” says Mark Kauzlarich. The previous presidential contest, in 2012, got him hooked on the Instagram feeds of political photographs—an interest that inspired the Wisconsin native to move to Iowa in late 2015. On his second day there, Reuters assigned him a photo shoot with Ben Carson, a gig that evolved into a 34-day assignment. Kauzlarich quickly had to learn the rules of the game in the field – from dealing with the candidates’ press managers to booking hotel rooms when you don’t know where and when your day will end. “The logistics of covering a campaign keeps you very busy,” he says.

In total, Kauzlarich spent 101 days in Iowa.

Though Kauzlarich had at first exercised caution, photographing the campaign events in the most literal way possible, he soon started taking more visual risks, focusing on the candidates’ personalities and trying to catch them during downtime rather than public events.

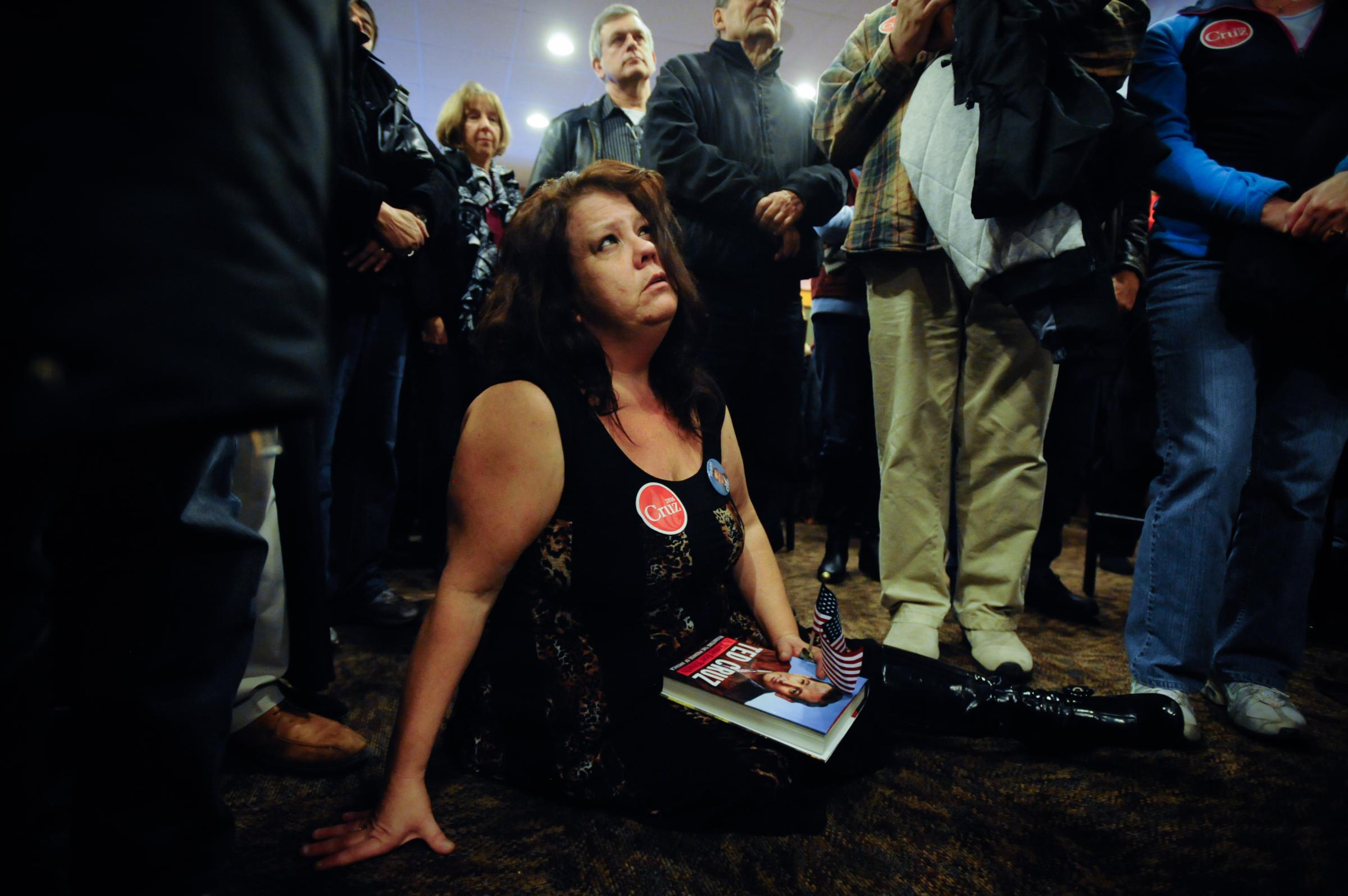

Those more private moments could be hard to come by. Kauzlarich remembers boarding Ted Cruz’s bus in January and quickly realizing that access to the candidate would be hard. On the second day, he started negotiating with Cruz’s staff. Two more days passed before the campaign staff allowed him, along with Eric Thayer of the New York Times, to spend a few minutes photographing the senator as he spoke with his advisers between stops. “Certain candidates are more receptive to having cameras around, some are more able to tune out the distraction of having a photographer in the room or nearby, and some just (understandably) want a break from the media or the public,” he says. But when Kauzlarich is given the opportunity to be a fly on the wall, he tries to blend into the scenery, he says, and interact with the candidate as little as possible.”

On the other hand, certain candidates were much easier for the photographer to make connections with, especially those who received less coverage in this year’s crowded field, like Mike Huckabee, Rick Santorum and Martin O’Malley, all of whom Kauzlarich covered. Huckabee in particular made an impression, remembering details about the photographers’ parents and hometown. “These conversations never have anything to do with politics,” Kauzlarich says, “but are a good reminder that the candidates are people first and foremost.”

Natalie Keyssar, on assignment for TIME

Before Natalie Keyssar embarked on her first presidential campaign, she studied the work of veteran political photographers such as Damon Winter and Christopher Morris. “My friend, Scout Tufankjian, has also done really fantastic work and gave me great advice,” she says.

Armed with that background, Keyssar arrived in Iowa on Jan. 25. “My first night I was covering a speaking event for the democratic candidates on CNN,” she says. “It was my first time covering a televised campaign event and I was struck by how tightly controlled we, still photographers, were.”

That ultra-controlled atmosphere can complicate things for a photographer, as multiple candidates vie for attention, often under unflattering fluorescent lights, and campaign staffs attempt to put forward certain narratives. Plus, everyone—from the candidates to the voters to the security guards to other journalists—is under a lot of stress. “It’s tricky to find the truth,” Keyssar says.

Despite these impediments, Keyssar has approached every event with the same goal: to seek the surprising details that will help define a candidate. “I’m looking for something that my friends and family at home wouldn’t know about the campaign trail,” she says. “I’m looking for images that make the viewer feel what I’m feeling when I’m at these events. It could be the TV lights in my eyes, or a moment when the candidate seems to relax their guard for a second. A lot of times it’s the faces in the crowd. Some look hopeful. Some look angry.”

If she had one piece of advice to give to other photographers looking to jump on the trail it would be to have patience. “Take some time to think about it,” she says, “then get really clear and specific with what you want to do and stick to it, because your instincts are going to tell you to race all the other shooters to the buffer zone. But, ultimately, most of your best shots just won’t happen there.”

Mark Abramson, freelancer, self-assigned

Mark Abramson’s first time on the campaign trail was at a Hillary Clinton town hall meeting in Manchester, N.H. The heavy security and scripted nature of the event were a turn-off for the 27-year-old photographer from New York, who soon decided to follow less popular candidates who, he says, “are much more loose in their style.” Using the fact that he wasn’t on assignment, Abramson came up with his own schedule, drawing up a game plan that would allow him to photograph in more personal settings, from private homes to diners. “Sometimes, you arrive and the scene is just not good. Some days you get really lucky, and others, not so much.”

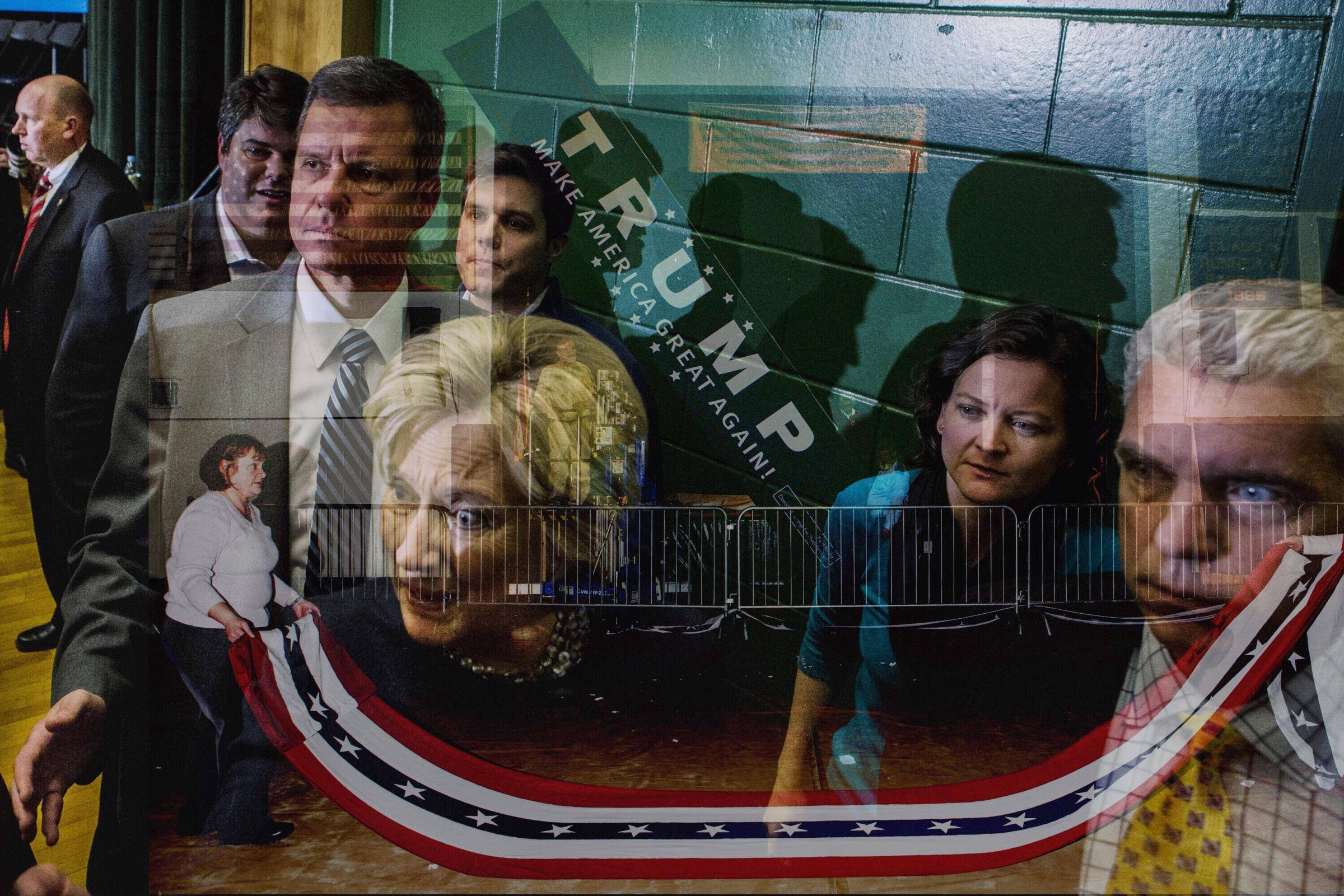

To further differentiate himself, Abramson has been shooting multiple exposure photographs, drawing his inspiration from his family’s own background. “I come from a Jewish immigrant family from the former Soviet Union and I have always been fascinated by the exaggeration within communist-era political propaganda,” he says. “If you look at a lot of those old posters you can see how surreal the composites are. Vast landscapes, the general population, all mixed in with a superimposed image of their great leader, like Vladimir Lenin.”

Abramson feels the surreal nature of the elections lends itself to that photographic approach. “It’s like a theater,” he says. “And there are all these actors that make up this really odd spectacle. It’s honestly one of the oddest things to cover because it doesn’t feel real, so everything in my mind tends to blend and become blurry. Everyone starts looking the same and sounding the same, and so in my head I am literally seeing these multiple exposures.”

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent.

Chelsea Matiash, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s deputy multimedia editor. Follow her on Twitter @cmatiash.

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com