Two women and a man are sitting next to each other, listening, from the front row, to Sen. Ted Cruz as he campaigned on Jan. 27. On the screen, one of the women is slowly turning her head towards her friend, while the man is looking up at the candidate. They are all enthralled; their otherwise imperceptible reactions – the movement of their eyes, the contraction of their muscles – take center stage as Christopher Morris’ camera pans the room.

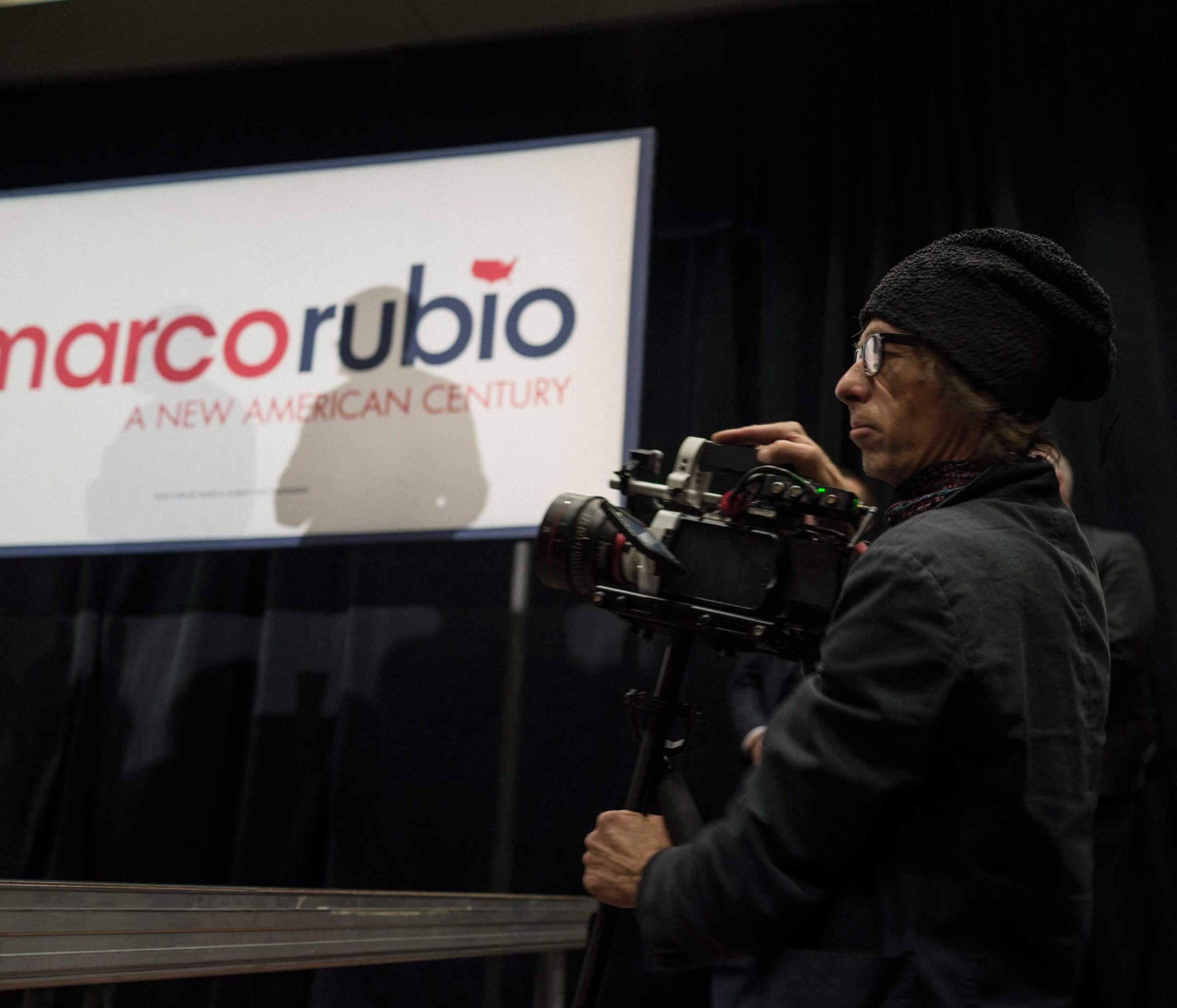

The clip lasts 10 seconds, but Morris’ camera movement that day – his sweep across that front row in that Noah’s Event Venue in St. Clive, Iowa – took less than a second to film using Vision Research’s Phantom, a high-speed camera that shoots more than 720 frames per second.

The result is an eerie, almost spiritual series of films on six of the campaign’s main candidates – Cruz, Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush. Six films that offer an unprecedented look at America’s political theater.

See all six The Candidates films and read Meghan O’Rourke’s introduction.

Morris is a veteran of political photography. In 1999, after years photographing conflict, he came back to the U.S. to cover John McCain’s presidential campaign, the ensuing White House race before becoming TIME’s White House photographer. During his years in Washington, he produced two books – My America and Americans – that are widely credited with transforming the way politics was photographed, influencing generations of photographers and blurring the lines between straight photojournalism and art.

That particular style – the somber colors, the skewed perspective – is present, and even amplified, in Morris’ series of slow-motion films.

“I have a real hard time with a lot of manipulation and distortion in photography and in filmmaking,” he says. “So I was a little concerned looking at the clips that people would think it was very un-journalistic. But it’s very realistic because what’s happening is [that] you’re slowing time down.”

In fact, Morris links this latest work to the altered state our consciousness enters in life-threatening situations that Morris himself has experienced while covering war and violence. “When your body senses death and fear, it puts you in this altered state, this suspended animation,” he says. “And that’s what the Phantom captures.”

The $80,000 camera is a difficult beast to master—it’s always on, recording every single second of footage on its buffer. While a photographer or filmmaker can choose when to start or stop shooting, a Phantom user can only select his shots in the seconds following the desired moment. “It’s a process called triggering,” says Edward Richardson, a Phantom camera technician and operator, who worked with Morris on this TIME assignment.

Once the photographer has triggered the camera, the last second of footage will be transferred from the device’s RAM buffer to a hard drive. The process can take several minutes, rendering that particular model – Morris used the smaller, portable Miro 320S camera – useless during that time. That can be daunting for a photographer used to always getting the shot. “Sometimes we would be trying to get something from the crowd and all of the sudden, Hillary Clinton has walked over to where we are and we have to wait two minutes for the camera to be ready again and he’s there dying,” says Richardson. “But he adapted to it so quickly.”

For Morris, all six films offer an in-depth, altered look at the political theater – one that frightens him, he admits, especially when coupled with the stretched, slightly creepy audio that he recorded at the events. “I didn’t try to make anybody look bad. I didn’t try to make anybody look great. I was just trying to show this altered state of time with each candidate and this ceremonial ritual of a candidate trying to seduce the public into voting for them.”

Studying that process changed how Morris saw the candidates. “I went in thinking I would have six different films,” he says. “I had this preconceived idea what a Trump rally would be like, what a Sanders rally would be like, what Clinton would be like, but all of that went out the window. They’re really similar.”

Christopher Morris is an award winning TIME contract photographer since 1990 and is a founding member of the VII photo agency. He is the author of My America and his latest book Americans.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent. Diane Tsai is a video producer at TIME. Follow her on Twitter @diane_tsai. Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Diane Tsai at diane.tsai@time.com