Gabriela Alves de Azevedo, 20, clutched the arm of her boyfriend with trepidation as a rainstorm, as severe as many in this corner of northeastern Brazil could remember, thundered outside the family’s concrete terraced house.

In her other arm she cradled her 3-month-old daughter Anna Sophia, who gargled gently with eyes closed as her hands grasped at air. Born weighing 6.8 lb. after a “perfect” pregnancy, it was only after the birth that the worry began.

Read More: WHO Declares Zika an International Health Emergency

“It was just her head,” Azevedo says. It was just a little bit too small. Her daughter was later confirmed to have microcephaly, the condition that has surged alarmingly in newborns in Brazil since last year and often causes brain damage. Instead of coming home, her daughter remained in the hospital for 26 days for tests.

Most everything else about her is normal, the family says, except for glaucoma, cataracts and acid reflux. She does not seem in pain or cry more than other infants, as can happen in some severe cases, and her hearing appears sound. But Azevedo and her boyfriend Leandro Brito Nery, 29, can now only wait. Doctors say they cannot yet tell if Anna Sophia will be able to walk or talk, or even how long she will live.

“It was difficult at first, you feel this depression come over you,” Azevedo says. “But now we do not lament that she is different. We have so much hope for her life.”

The city of Recife, with a metro population of 3.9 million, has become the center of a health crisis, with a surge of microcephaly cases that may be linked to the rapidly spreading tropical Zika virus, as is believed by health officials in Brazil.

Read More: Inside a Center for Babies Born With Zika-Related Birth Defects

Doctors have identified 4,180 suspected cases of microcephaly in Brazil since October, with nearly a third in the state of Pernambuco — of which Recife is the capital — and almost 9 in 10 in the northeast region, known for its beautiful beaches and stark poverty. Two hundred and seventy have been confirmed as microcephaly, and six of those mothers are confirmed to have contracted Zika. Of the remainder, 3,448 cases are still being investigated, with 462 ruled to have been false alarms. In all of 2014, the country had 147 cases of microcephaly.

Here in Recife, hundreds of young mothers are going through the same emotions as Azevedo, and many can be found, visibly distraught, in the tattered waiting room of the Oswaldo Cruz public hospital, which is dealing with about 300 of the cases. “In 43 years as a doctor, I have seen outbreaks of polio and cholera but never anything as shocking as this,” says Dr. Angela Rocha, head of the infectious-disease unit. “The panic, stress and uncertainty of these women, it is difficult to watch.”

Like dengue, yellow fever and chikungunya, the Zika virus is borne by mosquitoes and has generally been confined to equatorial Africa and Asia. Its presence in Brazil was confirmed in May 2015, but it was not initially considered a threat. The virus causes a rash and relatively mild flulike symptoms in 1 out of every 5 people who contract it; the rest generally show no symptoms. It is estimated to have already infected between 400,000 and 1.4 million people in Brazil and is spreading rapidly through Latin America.

It was the birth of a boy with microcephaly in a small town in the arid countryside of Pernambuco in July that began the chain of events that led to the World Health Organization to declare today that Zika is an international public-health emergency, the first since Ebola. The boy, a twin, was born with a head circumference of 28 cm, says Dr. Vanessa Van Der Linden, a neuro-pediatrician who saw him in the first week of August at the Hospital Barão de Lucena in Recife, where she works.

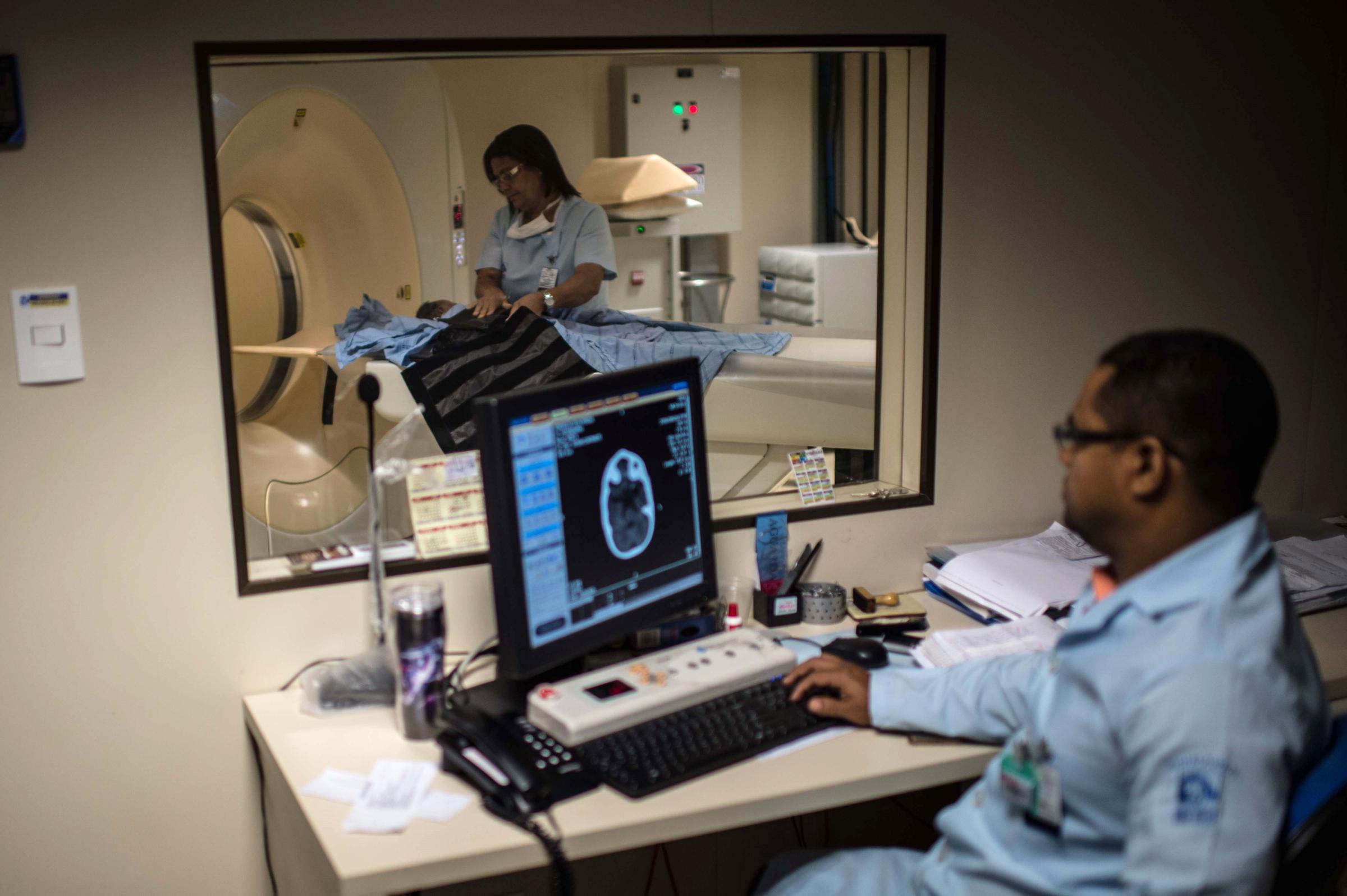

“It was really obvious, disproportional,” she says, holding a graph showing the normal range for head circumference, between 32 cm and 38 cm. During the pregnancy the mother had suffered a red rash on her arm. A CT scan indicated the cause of microcephaly was likely an infection rather than a genetic abnormality.

In the middle of September, Van Der Linden saw another three babies with suspected microcephaly in one day and then two more the next week. Normally, she would see one a month. Later that month her mother, also a neuro-pediatrician in Recife, called her and said she had seen seven such patients on the same day. The younger doctor estimates she has now seen 40 such cases, a near 10-fold increase.

The two doctors notified state health officials in early October, who began to investigate a sample of cases. By early November, Brazil’s Health Ministry declared a national emergency based on 141 cases in Pernambuco alone. By the end of November, 1,248 cases were suspected nationally. By Christmas Eve, it was 2,782.

“The increase in the circulation of Zika is a new public-health phenomenon,” says Recife’s health secretary, Dr. Jailson Correia, a pediatrician who studied infectious diseases at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the U.K. and is now leading his city’s fight against Zika. “We had no previous experience.”

The crisis comes at a bad time and a bad place, with Brazil facing its worst recession since 1901, and the northeast region historically one of the country’s most deprived. In Pernambuco, more than 650,000 households live on less than the minimum wage of $220 a month, according to the most recent census.

All the doctors and officials who spoke to TIME admitted Brazil’s public-health system is seriously underfunded. The city of Recife asked for $7.25 million in federal money to fight the crisis and has so far received $320,000, Correia says. As he gives an interview, the lights in the city hall flicker on and off in the storm.

A vaccine remains many years away, but the likely commercial demand for one could hasten progress, says Professor Scott Weaver, director of the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity at the University of Texas Medical Branch. “Within three years I would expect there to be the first clinical trials on humans,” he says. “But after that it becomes more challenging as you will need to find a large exposed population to be tested on — which might not be immediately possible.”

See the Impact of Zika in Brazil

For now, much effort in Brazil is being put into educating the public to the risks. “While we do not have a vaccine against the Zika virus, the war must be concentrated on the elimination of breeding grounds of the mosquito,” President Dilma Rousseff said last week. “Getting rid of Zika is the responsibility of all of us.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com