The Western films that are nominated for Academy Awards typically arrive in Hong Kong’s cinemas in one fell swoop around the New Year, but the most talked-about movie of the last month has been a local picture called Ten Years, a collection of five impressionistic vignettes that imagine a Hong Kong a decade from now. This Hong Kong is a city on the cusp of dystopia, where government officials devise assassination plots to justify enacting martial law and children are conscripted to a Hitler Youth–like organization as spies who report their parents’ political treason.

It is a Hong Kong that is firmly under the rule of China’s Communist Party, being punished for once believing that it could be otherwise. Taxi drivers who fail a Mandarin proficiency test (most Hong Kong people are native Cantonese speakers) are banned from picking up passengers downtown or at the airport, and the word local — in any language — is illegal, as it implies an allegiance to Hong Kong over Beijing. A recurring motif: time-lapsed shots of a sinister fog spilling over the city’s skyscrapers, blanketing the glow of the city.

“I think it’s quite realistic, really — it could happen within five years,” 36-year-old moviegoer Cheung Siu-chung says of this vision. It’s a rainy Monday night after the coldest day in Hong Kong in six decades, and the United Artists cinema at Cityplaza shopping mall is desolate until the end of the screening of Ten Years, which was sold out. “And frankly, we can’t do anything about it. It’s obvious now that Beijing controls everything. The local government won’t help us; the police won’t help us.”

Ten Years opened on Dec. 17 at a theater across Victoria Harbour, where it quickly beat Star Wars: The Force Awakens at the box office. Less than two weeks later, on the day before New Year’s Eve, a 65-year-old publisher named Lee Bo disappeared. He was last seen at his warehouse on Hong Kong Island, which housed the books that made his publishing house, Mighty Current Media, infamous and wildly popular: salacious novels and purported histories describing the secret gay sex lives of Chinese politicians and, in meticulous detail, how China’s First Lady Peng Liyuan lost her virginity.

Lee’s disappearance was not without precedent: four of his colleagues had gone missing in October while traveling outside of Hong Kong; one, Gui Minhai, resurfaced earlier this month on China’s state television broadcaster, slumped over and seemingly distressed, making a clearly scripted confession to a fatal drunk driving accident that happened 11 years ago. Gui, who held a Swedish passport, had returned to the mainland, he said, because “his roots are in China.”

Shortly after Lee went missing, he contacted his wife to tell her that he had willingly traveled to across the Chinese border to “assist” with a police investigation. It’s easy to get to the mainland from Hong Kong — an hour or so from downtown if you take the MTR, Hong Kong’s immaculate metro system — but Hong Kongers need to produce a special travel permit to do so. Lee’s wife later found his permit at home.

Earlier this week, she went to the mainland to met with him at a “secret” location under dubious circumstances, returning to Hong Kong with a letter he had putatively written — claiming that he was happy and healthy, and instructing Hong Kong police to stop wasting resources investigating his case.

“The fact that Lee Bo has stated in his letters that he is unhappy with the controversy created by his disappearance seems to indicate that the authorities would prefer to handle the booksellers case without public oversight and without reference to Chinese and international law,” William Nee, who researches China at Amnesty International’s East Asia office in Hong Kong, says.

Ironically, Lee’s request that Hong Kong authorities stop pursuing his case seems superfluous. In the month that has passed since he was last seen in Hong Kong, lawmakers in the territory have reacted with ambivalence, even as Western governments have decried the case as a potential violation of human rights and Hong Kong jurisdiction. Earlier this month, Jasper Tsang, the pro-Beijing lawmaker who heads Hong Kong’s legislative body, asked mainland officials to publicly say that their involvement with Lee did not violate Hong Kong’s constitution, which grants the territory a “high degree of autonomy” within the broader umbrella of Chinese rule. But no direct response came, and the Hong Kong government has not publicly followed up.

“The Hong Kong government appears to now have considerably diminished autonomy, and the Liaison Office [Beijing’s headquarters in the territory] is strengthening its position,” Steve Vickers, CEO of Steve Vickers and Associates, a specialist political and corporate-risk consultancy, says. “The Liaison Office operates outside of the Hong Kong legal system, and Hong Kong people cannot question its actions or even seek a judicial review. That is one of the major factors leading to unease.”

“From the mainland public security perspective, I suspect [mainland officials] see the booksellers as a direct challenge to the authority of the state. The bulk of clients for these booksellers are mainland tourists and the security services view the publishers as proxies for representing hostile or foreign forces,” Vickers says. “I think the current action is calculated to cause people to keep their heads down when it comes to producing seditious material as the Chinese public security see it. But it has also sent a chill through the business and social arenas in Hong Kong.”

This unease — the fear of mainland power subsuming Hong Kong and erasing its freedoms — has a long history. By some estimates, as many as a million Hong Kongers fled the territory to countries like the U.S., Canada and Australia in the years leading up to 1997, when the U.K. was scheduled to relinquish its last significant colony to China. A century and a half of colonial rule had built Hong Kong as a freewheeling, free-market metropolis; China was an authoritarian gerontocracy with a plain record of squashing dissent with lethal force.

To compromise, Britain would return Hong Kong as a Special Administrative Region: a state within a state, essentially, with its own laws and politics. Under the “one country, two systems” schema outlined in the Basic Law, as Hong Kong’s constitution is called, the territory falls under Beijing’s ultimate jurisdiction but possesses a “high-degree of autonomy,” political and otherwise.

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

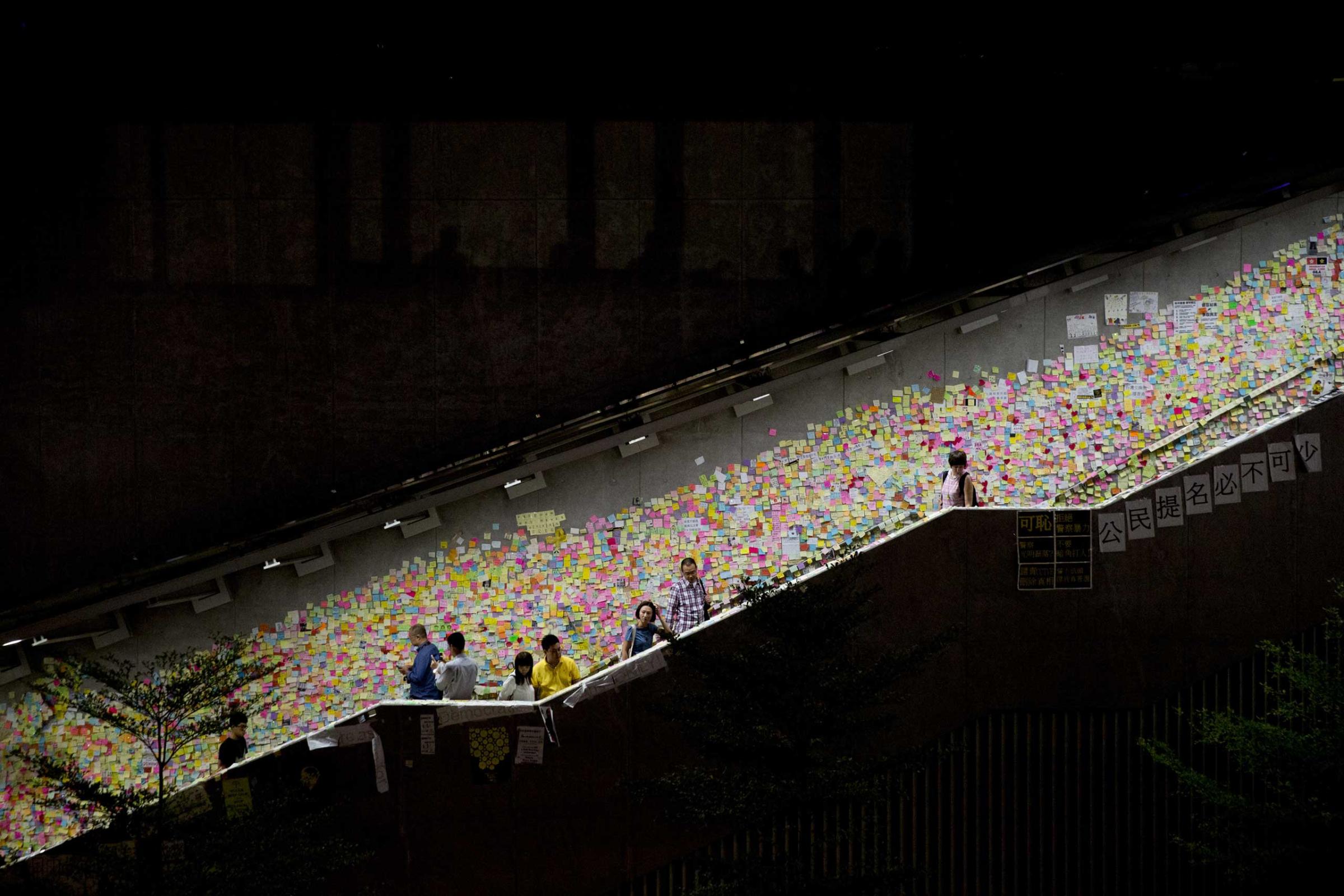

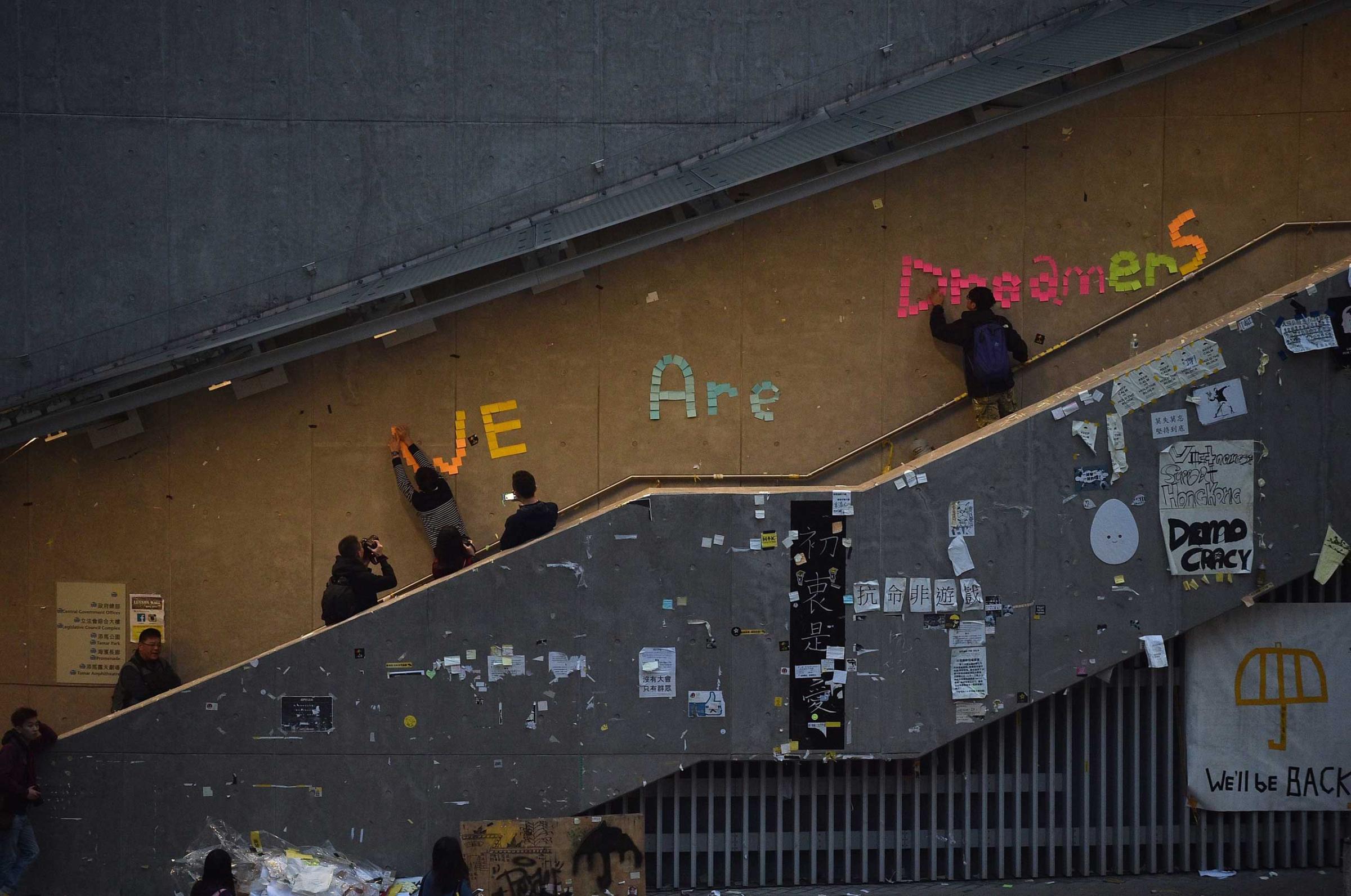

For 11 weeks in the autumn of 2014, hundreds of thousands of Hong Kongers occupied the city’s central business district to prove to Beijing — and perhaps to themselves — that, as many protest banners defiantly declared, Hong Kong is not China. The protests’ leaders — students who were toddlers when the Union Jack was lowered — demanded the right to directly elect Hong Kong’s top official, called the Chief Executive, who is appointed by an electoral college and commonly seen as Beijing’s stooge.

But more fundamentally, the 79-day street protest known as the Umbrella Revolution was about democracy — which, in Hong Kong terms, means the ecosystem of liberties best defined by what it is not. And it is not mainland China.

At its worst, Hong Kong’s alienation from China can come across as snobbery. Nearly 50 million mainland tourists come down to Hong Kong each year, mostly to shop, and there are myriad videos on YouTube of Hong Kongers angrily lashing out at them for breaching local etiquette — usually aboard the subway, where loud conversation is a faux pas and eating a snack can get you a $250 fine. But this is one small facet of a civic pride that is earnest, entrenched, and increasingly anxious about its future. It is increasingly impelled by the deep fear that “Hong Kong will stop being Hong Kong,” as Joshua Wong, the scrawny student activist who stood as the protests’ figurehead in 2014, put it to me on Jan. 12.

We spoke after a conference at the University of Hong Kong, where Wong and two other prominent activists — Martin Lee, the 77-year-old former legislator known here as the “father of democracy,” and activist-law professor Benny Tai, a quarter-century younger — sat together onstage to discuss the future of their freedoms.

“With the incident of the missing booksellers, ‘one country, two systems’ has eroded,” Wong said. “I have no option but to fight. I’m a student in serious debt, so I can’t migrate from Hong Kong, like the baby boomers could. My generation is tied to this place.”

“It’s possible that we won’t ever see true ‘democracy’ in Hong Kong, but we need more than democracy — we need to implement ‘one country, two systems’” Martin Lee told the audience. “Hong Kong is no longer the same. The booksellers have disappeared. But I will keep fighting.”

Others are less confident. Earlier this month, a Hong Kong publishing house known for printing controversial political books announced that it had suspended its plans to publish a work critical of Chinese President Xi Jinping. The publishing house’s chief editor, Jin Zhong, told local media that he would be leaving Hong Kong for New York. He said he didn’t want to be the next one to disappear.

“We can feel the atmosphere changing,” Paul Tang, who owns another bookstore known for its inventory of scandalous political texts, told TIME on Friday. For now, he remains defiant. “I don’t plan on self-censoring our inventory — there’s still a big market for these books,” he says, “and I don’t want to give up our main source of income. We rely on these books to pay the rent.”

Tang noted that other bookstore owners had stopped selling books that are banned in the mainland, and said that while he understood their decision — and that he would follow suit if he began to feel personally threatened — “the only people who can preserve Hong Kong’s remaining freedom are Hong Kongers.”

“But,” he paused, “they’ve started targeting publishers, and so in the future I may need to find some other way to make money.” And then: “Maybe I’ll start selling the iPhone 7 when it comes out.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com