Just over a year ago, Gui Minhai, a publisher specializing in juicy political tales banned in mainland China, jotted a note on his iPad. “Writing progress,” read the memo, detailing the prolific Chinese-born publisher’s upcoming projects. A future book was titled, with characteristic relish, The Pimps of the Chinese Communist Party, another The Inside Story of the Chinese First Lady. The naturalized Swedish citizen was also working on another project, his confidants say, one that may have gotten him in serious trouble with the Chinese government: a tell-all–who knows how truthful?–of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s rumored female liaisons.

On Jan. 17, Gui showed up on Chinese state TV in a video that would have strained belief as a plot point in his best-selling but, at times, questionably sourced books on the political and sexual peccadilloes of China’s ruling class. In the video, Gui, a Manchurian with broad shoulders and thick hair, slumps forward, face crumpling, as he says he voluntarily returned to China to face justice for a fatal drunk-driving accident in his eastern Chinese hometown of Ningbo 12 years ago. After the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, Gui, once a poet, had picked up Swedish citizenship during a period of self-exile. But in the 10-minute TV broadcast, he distanced himself from any Western protection. “Although I have Swedish citizenship, I truly feel that I am still Chinese and my roots are in China,” he said. “So I wish the Swedish government will respect my personal choice, respect my rights and privacy and let me solve my own problems.”

The tearful confession was Gui’s first appearance since the 51-year-old vanished last October from outside the gates of his condominium in the Thai beach town of Pattaya. Four other men associated with Gui’s Mighty Current Media have also disappeared, three while traveling in southern China on separate occasions last fall. The most recent to go missing was Lee Bo, Gui’s business partner. Lee, who holds a British passport, was last seen on Dec. 30 in Hong Kong, where he and his wife ran a bookshop hawking hundreds of salacious political accounts to curious mainland Chinese.

There is no official record of Lee’s exiting the former British colony, which is governed by different laws than the rest of China as part of a so-called “one country, two systems” policy that ushered in Hong Kong’s return to China in 1997. Yet days after his disappearance, a fax in Lee’s handwriting appeared, explaining that he had used his “own methods” to travel to the mainland and was busy assisting in an unnamed investigation. (His letter and Gui’s confession used similar language.)

On Jan. 18, Chinese officials finally responded in writing to Hong Kong police queries on Lee’s whereabouts: he was “understood” to be in mainland China. British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond had previously labeled the mysterious circumstances of Lee’s journey to mainland China as “an egregious breach” of Hong Kong’s autonomy. Even Tsang Yok-sing, the pro-Beijing leader of Hong Kong’s legislature, called into question China’s handling of the missing publishers, particularly the broadcast of Gui’s video, which he noted “did not seem to be able to calm the public.” For a Beijing loyalist like Tsang to note any anxiety was proof of just how unnerved people in Hong Kong are about the possibility of China running roughshod over local law. In a Jan. 19 op-ed, China’s state-linked Global Times chastised the Hong Kong citizenry for politicizing the publishers’ case, criticizing the territory for acting as “the bastion of any extreme or illegal actions that would shake the mainland’s political systems.”

Fax and video reassurances notwithstanding, it does seem more than coincidence that five people linked to politically sensitive exposés all went missing, two outside mainland China. (The Chinese Foreign Ministry has not responded to queries on the publishers’ whereabouts.) The disappearances raise concerns not only about the possible extraterritorial exploits of Chinese security agents–the Soviets were masters of such abductions–but also the inability or unwillingness of other governments to counter a more activist China.

For decades, Beijing adhered to a noninterventionist approach to foreign affairs, lest other nations scrutinize its record at home. But under Xi, China has pursued a far more energetic international policy, designing and launching new multilateral organizations; clashing with neighbors in territorial disputes; and pressuring foreign governments to do its bidding, often by dangling its economic largesse as a reward. Some of these actions bespeak a nation that is growing into its natural role as a major player in global politics. Still, the question remains: Is the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) now in the business of kidnapping, both at home and abroad?

China today boasts the world’s second largest economy, and more than 100 million of its newly moneyed citizens travel the globe. Yet growth is slowing, and income inequality has surged. On Jan. 19, China’s official 2015 GDP figures came in at 6.9%, likely inflated by state planners but still the worst showing in 25 years. Since rising to the top of the CCP hierarchy in late 2012, Xi has been charged with an unenviable task: ensuring the relevance of a party that has ruled for 66 years, even as its primary achievement–the biggest economic expansion the world has ever seen–is losing its shine.

One of Xi’s responses to the CCP’s existential challenge has been to double down on repression, swatting down those who question the party’s wisdom. Over the past couple of years, hundreds of freethinkers have been locked up in China, from the nation’s top female lawyer and a legal activist once lauded in state media to Christian pastors and a moderate Muslim academic. State censors have muted online dialogue and ramped up Marxist indoctrination for cadres and students alike. Even as official media promote the idea that China is a nation bound by rule of law, Xi’s ministers have campaigned against dangerous notions like civil society, freedom of the press and universal human rights. “I think Xi is very proud of where China has come from, and he should be proud of its economic and military strength,” says Roderick MacFarquhar, a China specialist at Harvard University. “But when he talks about China’s commitment to rule of law, he doesn’t mean it. He means rule by law in which people obey him.”

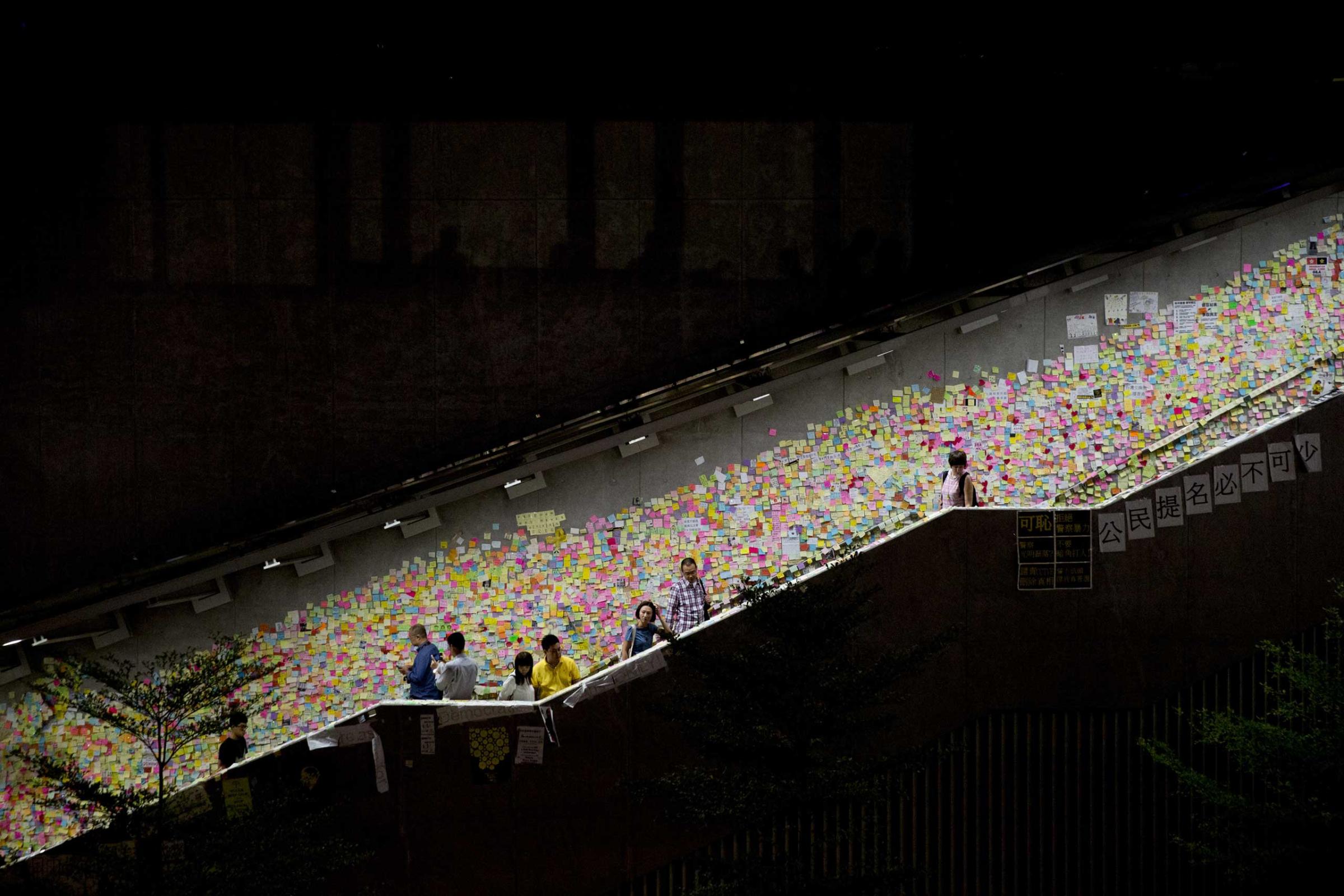

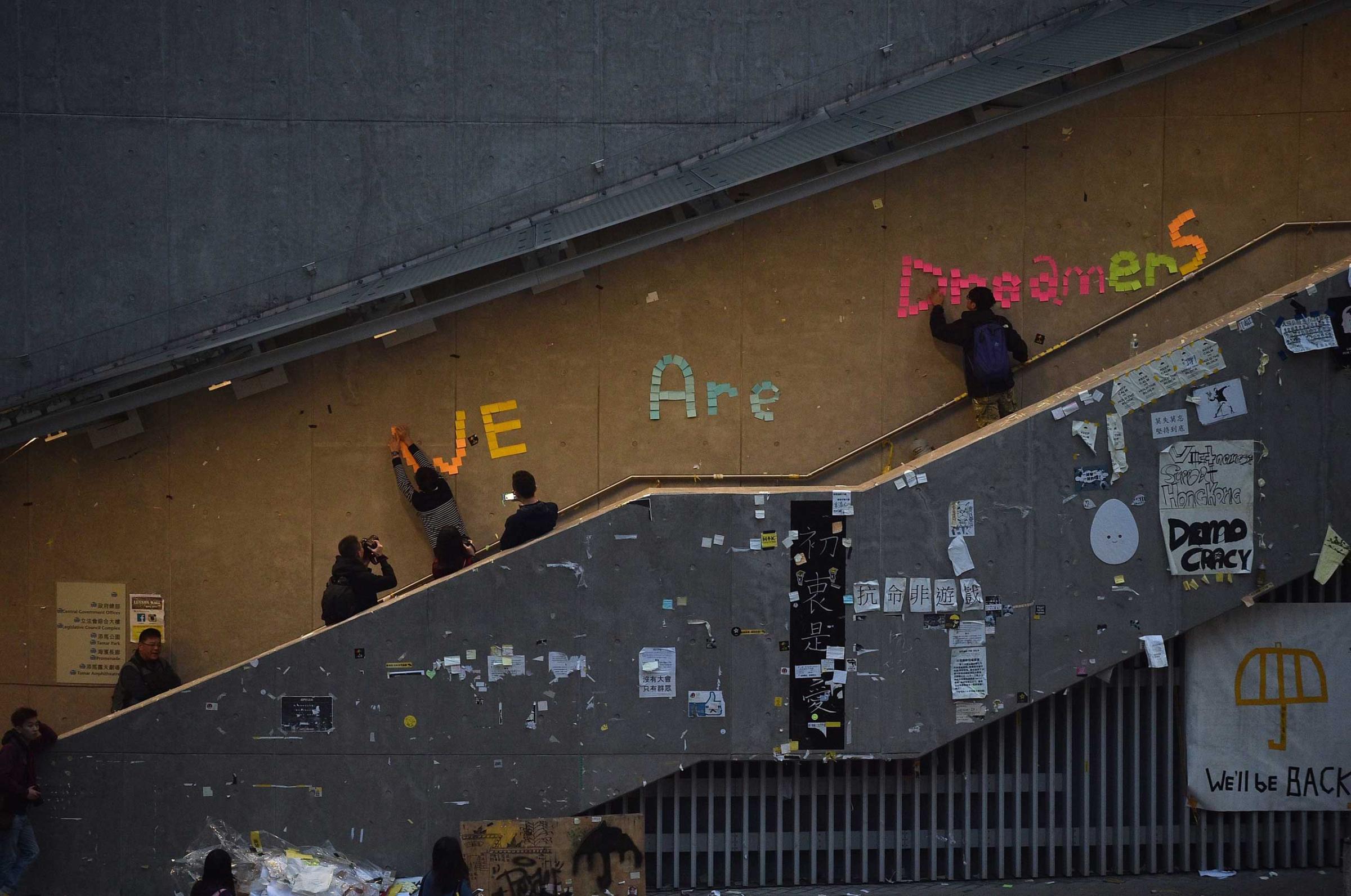

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

A succession of journalists, lawyers and bloggers–not to mention Gui–have appeared in confessional videos broadcast on state TV, even before their cases have gone to trial. The coerced feel of the videos gives an impression less of due process and more of state control. “Today’s culture of confession is not about accountability, clean government or a rules-based system,” wrote David Bandurski, a media analyst at the University of Hong Kong, in an essay last year. “It is about dominance and submission.”

The latest mea culpa was released through Chinese online media on Jan. 19. In the video, another Swedish citizen, Peter Dahlin–who was detained in early January in Beijing, where he ran an NGO that helped human-rights defenders–appears to admit to actions that the Xinhua state news agency said “sponsored activities jeopardizing China’s national security.” “I violated Chinese law through my activities here,” Dahlin says in the video. “I’ve caused harm to the Chinese government. I’ve hurt the feelings of the Chinese people. I apologize sincerely for this.” In the broadcast, one person who said he worked with Dahlin dubs the 35-year-old Swede a “spokesman of the foreign anti-China forces in China.”

For all its ability to elicit such confessions, China’s crackdown feels both brutal and brittle–a mighty ruling party spooked by unarmed poets, feminists and lawyers, none of whom are calling for an end to communist rule. “Maybe the Chinese government has power,” says Yi Feng, a Chinese dissident who fled to Thailand last September with his young son. “But it doesn’t have legitimacy.”

If Gui were planning to return to China to assuage his troubled conscience, he gave no sign of an impending life change. At his spacious Pattaya condominium, which he bought around a year ago, a new cabinet delivered days after his disappearance stands in the middle of the room, swaddled in plastic. On a desk, which afforded Gui an expansive view of the Gulf of Thailand, two days-of-the-week pillboxes sit, still filled with medicine for the days following his disappearance. Gui’s swimming gear rests in a bag on a nearby table, awaiting his usual daily swim.

Gui was out shopping for groceries on Oct. 17 when a man speaking broken Thai and no English showed up at the gate of the Silver Beach condominium. (His image was recorded on the building’s CCTV.) When Gui eventually returned, he asked the compound’s guard to take his groceries up to his apartment and leave them in the hallway. The two men climbed into Gui’s white hatchback. That was the last sighting of the publisher responsible for up to half of the pulp political books available in Hong Kong.

For a couple of weeks, Gui kept in contact with condo employee Pisamai Phumulna by phone, much as he did when he was in Hong Kong and needed her help in watering plants or ensuring bills were paid. Later on Oct. 17, he called, asking her to put the groceries–smoked salmon, bread and eggs, among other items–in the fridge. Then in early November he rang again, saying that friends would be coming by to pick up a few things from his home and to please let them in. Four men showed up, one wearing a straw hat and sunglasses. Two spoke native Thai, while the other two spoke only Mandarin. Their images were also captured by the building’s CCTV.

The men stayed in Gui’s apartment for less than half an hour and took, at the very least, a laptop that had been on his desk. The printer’s cartridge also appears to be missing. Apart from shelves lined with copies of Mighty Current’s books, such as The Mystery of Xi’s Family Fortune and The Dark History of the Red Emperor, the apartment now contains not a single document connected to his work. It’s not clear if Gui’s Pattaya holiday home ever housed such papers, although the publisher often edited and commissioned new books while in Thailand, according to two of his writers who live in the U.S. They both believe he was soon to publish a book about Xi’s past female companions. (Xi is married to his second wife Peng Liyuan, a former singer in the People’s Liberation Army who was once far more famous than her husband.) Gui’s friends soon became worried, particularly because he had failed to communicate with printers about an upcoming book. One friend contacted Pisamai. When Gui called her next in mid-November, again from an unknown foreign number, she told him his family was concerned. He hung up and never called again.

Despite Pisamai’s making a report at a local police station, no Thai or Swedish authorities have visited Gui’s Pattaya home. Meanwhile, in his apartment, a poem by William Butler Yeats, “When You Are Old,” is filed away, among quotidian notes-to-self to buy medicine and tweak wi-fi routers. Gui studied history at China’s prestigious Peking University. Fellow poet Bei Ling, who was once jailed in China before going into exile overseas, remembers a passionate young man who thrilled at the power of words. In the mid-1980s, at a time when unauthorized translations of Franz Kafka could be a crime, Gui and other Beijing poets sneaked into salons held in foreign diplomatic compounds and read whatever samizdat Western literature they could find. As censorship loosened by the late 1980s, Gui studied comparative literature and published a book called A Guide to Twentieth Century Western Cultural History. Then the bloodshed at Tiananmen forestalled further political reform in China for years.

Gui’s writers are now jittery. If the Mighty Current five have all ended up in Chinese detention, what safety is guaranteed for the publishing house’s authors? Chinese dissidents living overseas are also nervous–particularly those in Thailand, which has traditionally welcomed hundreds of thousands of refugees from all over the region. But the country’s ruling military junta has courted better relations with China, as ties with the U.S. have frayed because of the Thai army’s 2014 coup.

Last July, around 100 ethnic Uighurs native to the troubled, predominantly Muslim region of Xinjiang in China’s northwest were deported from Thailand. The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) called the mass extradition to China “a flagrant violation of international law” and worried that members of the Turkic minority would face persecution back home. Then, shortly after Gui’s disappearance in Pattaya, two Chinese dissidents who had fled to Thailand were sent home for immigration violations, even though they possessed official refugee documents. One was about to be resettled in a third country. The pair were arrested upon their forcible return to China. The UNHCR again rebuked the Thai government.

“I thought once I escaped China I would be safe,” says Yu Yanhua, another Chinese asylum seeker, as she waits in Bangkok for a UNHCR hearing to determine whether she will be classified as a political refugee, an often years-long process. After more than a dozen of her fellow democracy campaigners were detained in China as part of Xi’s crackdown, Yu paid smugglers to transport her to Thailand last year. The last leg of her journey involved 13 claustrophobic hours in the storage belly of a bus. Now the former Chinese state-enterprise employee, who has endured multiple stints in Chinese detention, worries about the unknown Mandarin-speaking men who have been tailing her and other Chinese dissidents in Bangkok for weeks. “If I disappear tomorrow, you will have no doubt about who took me,” Yu says. “The [Chinese] Communist Party is too powerful.”

—With reporting by Yang Siqi/Beijing

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com